The gay scene in 1930s London

For the majority of The National Archives records, same sex acts between men have been criminalised. Historically, various social and cultural practices could be used as evidence against individuals. Despite this, throughout the 1920s, 30s and 40s there was a thriving queer community who were able and willing to socialise despite the risk.

The National Archives collection has a particularly striking set of records around queer spaces from this era. A hidden network of private members clubs, pubs, restaurants and dancehalls provided a sanctuary where men could meet other men regardless of the law.

Knowledge of these spaces were spread through queer networks and many venues had an entrance price, which for some may have been prohibitive. However we can see a broad range of people, from various social backgrounds, gathering, from labourers to school masters.

Our records demonstrate a community resistant, resilient and determined in the face of persecution. These clubs and dancehalls were vital places where men, and some women, could freely meet, socialise and undertake relationships. One such club was the Caravan.

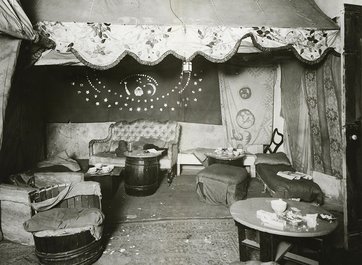

A photograph of the interior of the Caravan after being raided by police. Catalogue reference: DPP 2/224.

The Caravan Club

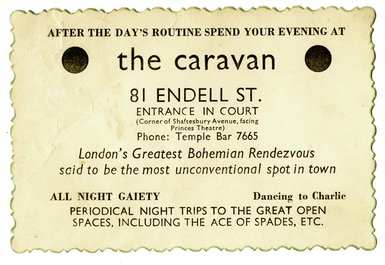

The Caravan Club, described in the 1930s as ‘London’s greatest bohemian rendezvous’, was a makeshift private members’ club in the basement of 81 Endell Street, Soho.

The club was run by Jack Neave, known as ‘Iron Foot Jack’ and William Reynolds, known as ‘Billy’. For the price of 1 shilling for members, or 1s 6d on the door, ‘all-night gaiety’ could be enjoyed while dancing to the music of Charlie, the club’s pianist. The dance floor could be found full of people, men would dance with men and women with women.

Translation

AFTER THE DAY’S ROUTINE SPEND YOUR EVENING AT

the caravan

81 ENDELL ST.

ENTRANCE IN COURT

(Corner of Shaftesbury Avenue, facing Princess Theatre)

Phone: Temple Bar 7665

London’s Greatest Bohemian Rendevous said to be the most unconventional spot in town

ALL NIGHT GAIETY Dancing to Charlie

PERIODICAL NIGHT TRIPS TO THE GREAT OPEN SPACES, INCDLUDING THE ACE OF SPADES, ETC.

AFTER THE DAY’S ROUTINE SPEND YOUR EVENING AT

the caravan

81 ENDELL ST.

ENTRANCE IN COURT

(Corner of Shaftesbury Avenue, facing Princess Theatre)

Phone: Temple Bar 7665

London’s Greatest Bohemian Rendevous said to be the most unconventional spot in town

ALL NIGHT GAIETY Dancing to Charlie

PERIODICAL NIGHT TRIPS TO THE GREAT OPEN SPACES, INCDLUDING THE ACE OF SPADES, ETC.

A card for the Caravan Club. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/758.

Public complaints

Metropolitan Police files indicate that from October 1933 the Caravan Club was kept under regular surveillance due to a number of complaints about the manner in which it was run.

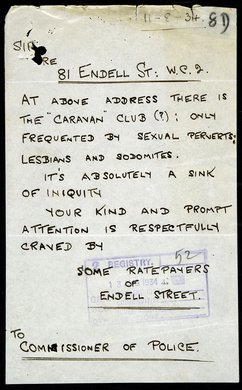

A note, signed anonymously by ‘Some rate payers of Endell Street‘, describes the club as ‘an absolute sink of iniquity… frequented by sexual perverts, lesbians and sodomites‘. Police surveillance was often implemented in response to pressure from the public or organisations such as the London-based Public Morality Council.

Transcript

11-8-34

Sir,

RE 81 Endell St: W.C.2.

At the above address there is the “Caravan” club (?): only frequented by sexual perverts, lesbians and sodomites

It’s absolutely a sink of iniquity

Your kind and prompt attention is respectfully craved by

Some ratepayers of Endell Street

To Commissioner of Police

11-8-34

Sir,

RE 81 Endell St: W.C.2.

At the above address there is the “Caravan” club (?): only frequented by sexual perverts, lesbians and sodomites

It’s absolutely a sink of iniquity

Your kind and prompt attention is respectfully craved by

Some ratepayers of Endell Street

To Commissioner of Police

The anonymous handwritten note complaining about the Caravan. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/758.

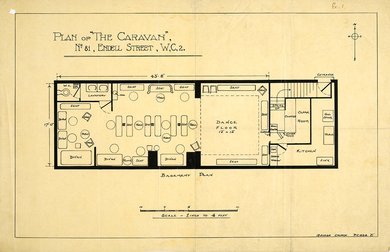

Police observed the Caravan Club over a few weeks, watching from an unused part of the Shaftesbury Theatre and an old school. An hour-by-hour account of men entering and leaving the club on 11th October 1933 paid particular attention to any conversation that suggested the club was being used as a brothel or, to use the legal term, a ‘disorderly house’.

The raid

In the early hours of the morning on 25 August 1934 a number of plain-clothed policemen entered the club pretending to be visitors. Divisional Detective Inspector Clarence Campion, the officer in charge of the raid, noted how he was able to introduce the officers without being noticed and described the scene that greeted him:

The small dance floor was crowded and the number was too large to allow dancing properly. Men were dancing with men and women with women… all the couples I saw were acting in a very obscene manner

Divisional Detective Inspector Clarence Campion. Catalogue reference: DPP 2/224.

Campion described the dramatic moment when the police revealed themselves:

I waited until the officers had taken up their positions allotted to them, and I then had the music stopped and said to the assembly: ‘Police Officers are in this place to arrest principals for maintaining the place in a manner likely to corrupt morals, and you are all aiding and abetting, and if you will remain quiet you will be taken to the police station as quickly as possible‘

Divisional Detective Inspector Clarence Campion. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/758.

Campion’s statement ends with an account of one of the attendees, Cyril de Leon, approaching the inspector in an extraordinary act of resilience: ‘Well I don’t mind this beastly raid, but I would like to know if you can let me have one of your nice boys to come home with. I am really good‘.

In the course of the raid 103 individuals, both men and women, were arrested and taken to Bow Street police station. During the arrest Cyril had to undergo the humiliating process of having his face tested for evidence of make-up with blotting paper.

The reason we have records about this unique venue is the policing. Often LGBTQ+ history appears in the archive because of criminalisation, leading to a wealth of records that would not otherwise survive. In these files are items used as evidence, including black and white interior photographs, floor plans and even letters.

A police sketch of the layout of the club on the night of the raid. Catalogue reference: DPP 2/224.

Recreating the Caravan (Opens in a new tab)

In 2017, in partnership with the National Trust, we were able to use our unique records to recreate the Caravan Club, back-to-back with its original location. This National Trust film by artists Simona Piantieri and Michele D’Acosta documents the reconstructed club.

Please note: the film contains performances that some may consider suggestive or inappropriate for younger audiences.

Cyril’s letters

Among the police witness statements and reports, there are personal letters that were used as evidence in court. These demonstrate a fascinating and rare personal reflection on what it meant to be queer at the time.

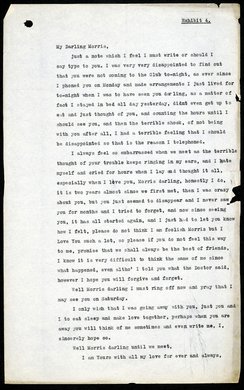

The first letter, addressed from ‘Cyril’ to ‘My darling Morris’, was found at the scene. Cyril begins: ‘I was very disappointed that you were not coming to the club tonight’, and describes ‘counting the hours until I could see you’, signifying the importance of the Caravan Club as a space where he could be himself; somewhere not just for casual sex, but where same-sex relationships and friendships were forged.

The letter continues:

I only wish that I was going away with you, just you and I to eat, sleep and make love together, perhaps when you are away you will think of me sometimes and even write me, I sincerely hope so

Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/758.

The note was found torn up under a divan in the club with a powder puff, the note was retyped for the police file.

Partial transcript

My Darling Morris,

Just a note which I feel I must write or should I say type to you. I was very very disappointed to find out that you were not coming to the Club to-night, as ever since I phoned you on Monday and made arrangements I just lived for to-night when I was to have seen you darling, as a matter of fact I stayed in bed all day yesterday, didn’t even get up to eat and just thought about you, and counting the hours until I should see you, and then the terrible shock, of not being with you after all. I had a terrible feeling that I should be disappointed to that is the reason I telephoned.

I always feel so embarrassed when we meet as the terrible thought of your trouble keeps ringing in my ears, and I hate myself and cried for hours when I lay and though it all especially when I love you, Morris darling, honestly I do, it is two years almost since we first met, then I was crazy about you, but you just seemed to disappear and I never saw you for months and I tried to forget, and now since seeing you, it has all started again, and I just had to let you know how I felt, please do not think I am foolish Morris, but I Love You such a lot

[…]

I only wish that I was going away with you, just you and I to sleep and make love together, perhaps when you are away you will think of me sometimes and even write me, I , sincerely hope so.

Well Morris darling until we meet,

I am Yours with all my love for ever and ever

My Darling Morris,

Just a note which I feel I must write or should I say type to you. I was very very disappointed to find out that you were not coming to the Club to-night, as ever since I phoned you on Monday and made arrangements I just lived for to-night when I was to have seen you darling, as a matter of fact I stayed in bed all day yesterday, didn’t even get up to eat and just thought about you, and counting the hours until I should see you, and then the terrible shock, of not being with you after all. I had a terrible feeling that I should be disappointed to that is the reason I telephoned.

I always feel so embarrassed when we meet as the terrible thought of your trouble keeps ringing in my ears, and I hate myself and cried for hours when I lay and though it all especially when I love you, Morris darling, honestly I do, it is two years almost since we first met, then I was crazy about you, but you just seemed to disappear and I never saw you for months and I tried to forget, and now since seeing you, it has all started again, and I just had to let you know how I felt, please do not think I am foolish Morris, but I Love You such a lot

[…]

I only wish that I was going away with you, just you and I to sleep and make love together, perhaps when you are away you will think of me sometimes and even write me, I , sincerely hope so.

Well Morris darling until we meet,

I am Yours with all my love for ever and ever

Cyril's letter to Morris, re-typed by police to use as evidence. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/758.

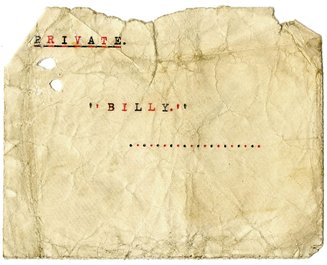

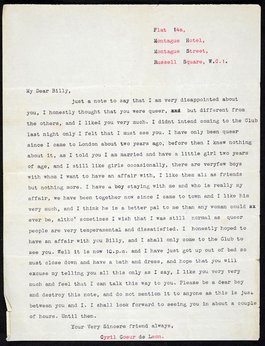

Another letter was found in a hotel bedroom on the Isle of Wight in a follow up investigation in the weeks following the raid. Written from Cyril to his dear friend Billy, the owner of the Caravan Club, the letter describes how he has ‘only been queer since coming to London two years ago‘, and reveals he has a wife and a little girl.

The note ends with the powerful words ‘Please be a dear boy and destroy this note’. Cyril was only too-aware of the implications if it was found.

Envelope for letter to ‘Billy’ from Cyril Coeur de Leon. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/758.

Transcript

My Dear Billy,

Just a note to say that I am very disappointed about you, I honestly thought that you were queer, but different from the others, and I liked you very much. I didn’t intend coming to the Club last night only I felt that I must see you. I have only been queer since I came to London about two years ago, before then I knew nothing about it, as I told you I am married and have a little girl two years of age, and I still like girls occasionally, there are very few boys with whom I want to have an affair with, I like them all as friends but nothing more. I have a boy staying with me and who is really my affair, we have been together now since I came to town and I like him very much, and I think he is a better pal to me than any woman could ever be, altho’ sometimes I wish that I was still normal as queer people are very temperamental and dissatisfied. I honestly hoped to have an affair with you Billy, and I shall only come to the Club to see you. Well it is now 10.p.m. and I have just got up out of bed so must close down and have a bath and dress, and hope that you will excuse my telling you all this only as I say, I like you very very much and feel that I can talk this way to you. Please be a dear boy and destroy this note, and do not mention it to anyone as this is just between you and I. I shall look forward to seeing you in about a couple of hours. Until then.

Your Very Sincere friend always,

Cyril Coeur de Leon

My Dear Billy,

Just a note to say that I am very disappointed about you, I honestly thought that you were queer, but different from the others, and I liked you very much. I didn’t intend coming to the Club last night only I felt that I must see you. I have only been queer since I came to London about two years ago, before then I knew nothing about it, as I told you I am married and have a little girl two years of age, and I still like girls occasionally, there are very few boys with whom I want to have an affair with, I like them all as friends but nothing more. I have a boy staying with me and who is really my affair, we have been together now since I came to town and I like him very much, and I think he is a better pal to me than any woman could ever be, altho’ sometimes I wish that I was still normal as queer people are very temperamental and dissatisfied. I honestly hoped to have an affair with you Billy, and I shall only come to the Club to see you. Well it is now 10.p.m. and I have just got up out of bed so must close down and have a bath and dress, and hope that you will excuse my telling you all this only as I say, I like you very very much and feel that I can talk this way to you. Please be a dear boy and destroy this note, and do not mention it to anyone as this is just between you and I. I shall look forward to seeing you in about a couple of hours. Until then.

Your Very Sincere friend always,

Cyril Coeur de Leon

Cyril's letter to Billy. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/758.

Trial

The case was heard at the Old Bailey, where there were 22 defendants, including three women. The majority of arrested individuals were found not guilty on the condition that they never frequent such a club again, but the punishment for the owners was severe.

Jack Neave and William Reynolds were found guilty of keeping a disorderly house described as ‘a place for people willing to pay for lewd, scandalous, bawdy and obscene performances and practices’.

Neave was sentenced to 20 months hard labour in prison, and Reynolds received 12 months. Cyril was committed to trial for aiding and abetting in keeping a disorderly house and found not guilty, despite the use of his letters as evidence.

The Caravan Club was forced to close. It had only been open for six weeks. Many other venues in the area continued to cultivate a queer clientele. Despite being under constant threat of police raids and arrests, queer venues like the Caravan remained important hubs for men and women to express their sexuality and love freely.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- DPP 2/224

- Title

- Director of Public Prosecutions case papers

- Date

- 1934

-

- From our collection

- MEPO 3/758

- Title

- Metropolitan Police files

- Date

- 1934–1941