‘Enemy aliens’ in Britain

From the outbreak of the Second World War to June 1940, German and Austrian civilians resident in the UK were classed as ‘enemy aliens’. Over 100 tribunal boards held across the country considered whether those aged between 16 and 70 were to be put into captivity. They were divided into three categories:

- Category A – to be interned

- Category B – to be exempt from internment but subject to restrictions decreed by a Special Order

- Category C – to be exempt from both internment and restrictions.

German and Austrian citizens that were considered to be a threat to national security were identified as Category A and classified as internees. They found themselves detained in camps, most of which were on the Isle of Man.

Onchan internment camp on the Isle of Man, 1943–1945. Catalogue reference: HO 215/302 (7)

The question of deportation

Following the fall of France in May 1940, the possibility of deporting internees was discussed at War Cabinet. The conversation turned to Italian citizens on 11 June, the day after Italy entered the Second World War. Prime Minister Winston Churchill told the War Cabinet he had instructed the Minister of Home Security to arrange for male Italians to be interned.

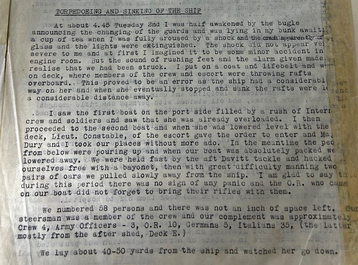

Over 6,000 German, Austrian and Italian prisoners of war and internees were then selected for deportation to Canada. Five ships were identified for the journeys: HMS Ettrick, SS Duchess of York, HMT Dunera, MS Sobieski, and SS Arandora Star. Most set sail over-capacity, including the Arandora Star, which had an insufficient number of lifeboats for its passengers.

Front view of SS Arandora Star, 1940. Catalogue reference: ADM 189/142.

The Duchess of York sailed first, embarking on 24 June with more than two thousand internees. The Arandora Star then set sail from Liverpool six days later. It had 1,213 internees aboard, including 473 Germans (among them 123 merchant seaman) and 717 Italians – around half of those Italians deemed to be Category A.

Seventy-five miles west of Ireland’s Atlantic coast the Arandora Star was attacked by U-47, a German U-boat led by the prolific submarine commander Gunther Prien. The ship sank, and more than half those aboard lost their lives. This included 470 of the Italian internees and 143 of the Germans.

Partial transcript

TORPEDOING AND SINKING OF THE SHIP

At about 4.45 Tuesday 2nd I was half awakened by the bugle announcing the changing of the guards and was lying in my bunk awaiting a cup of tea when I was fully aroused by a shock and the crash apparently of glass and the lights were extinguished. The shock did not appear very severe to me and at first I imagined it to be some minor accident in engine room. But the sound of rushing feet and the alarm given made me realise that we had been struck. I put on a coat and lifebelt and went on deck, where members of the crew and escort were throwing rafts overboard. This proved to be an error as the ship had a considerable way on her and when she eventually stopped and sank the rafts were left a considerable distance away.

TORPEDOING AND SINKING OF THE SHIP

At about 4.45 Tuesday 2nd I was half awakened by the bugle announcing the changing of the guards and was lying in my bunk awaiting a cup of tea when I was fully aroused by a shock and the crash apparently of glass and the lights were extinguished. The shock did not appear very severe to me and at first I imagined it to be some minor accident in engine room. But the sound of rushing feet and the alarm given made me realise that we had been struck. I put on a coat and lifebelt and went on deck, where members of the crew and escort were throwing rafts overboard. This proved to be an error as the ship had a considerable way on her and when she eventually stopped and sank the rafts were left a considerable distance away.

Extract from a report of Captain F J Robertson, Interpreter to Italian Internees, of the sinking of SS Arandora Star, 1940. Catalogue reference: HO 213/1722

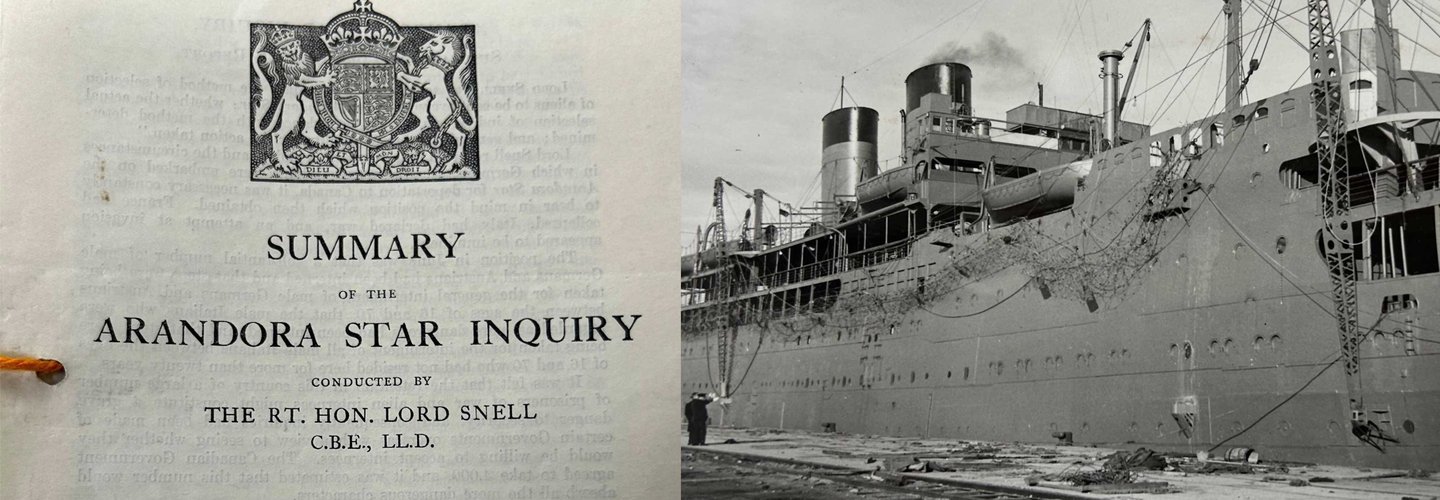

A Parliamentary inquiry

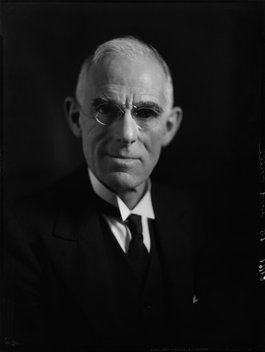

In August that year former Labour Member of Parliament Henry Snell, 1st Baron Snell, was appointed chair of an inquiry into the loss of the Arandora Star.

Henry Snell, whole-plate film negative by Bassano Ltd, 7 April 1936 © National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

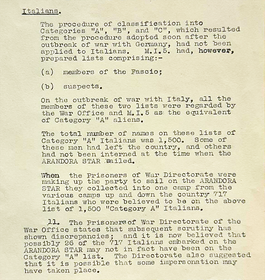

Lord Snell noted that while all of those on board the Arandora Star were considered to be Category A and dangerous characters, in the case of the Italians, none had sat before tribunal boards to ascertain how dangerous they were. Instead, the Security Services created lists of those to be deported based on whether or not they were members of the Italian Fascist party. The inquiry noted that little consideration had been given to those who were nominal members of the party, rather than being ardently Fascist.

It was found that many of those Italians who had died had sympathies that were wholly with the UK, and many had resided in the UK for several years. One of the Italians deported had lived in the UK for over 20 years, and some were deported in error, as they had never been members of the Fascist party.

Lord Snell concluded that the government had laid down no definite instructions on how to select foreign citizens to be sent overseas.

Partial transcript

...When the Prisoners of War Directorate were making up the party to sail on the ARANDORA STAR they collected into one camp from the various camps up and down the country 717 Italians who were believed to be on the above list of 1,500 "Category A" Italians.

11. The Prisoners of War Directorate of the War Office states that subsequent scrutiny has shown discrepancies; and it is now believed that possibly 26 of the 717 Italians embarked on the ARANDORA STAR may not in fact have been on the Category "A" list. The Directorate also suggested that it is possible that some impersonation may have taken place.

...When the Prisoners of War Directorate were making up the party to sail on the ARANDORA STAR they collected into one camp from the various camps up and down the country 717 Italians who were believed to be on the above list of 1,500 "Category A" Italians.

11. The Prisoners of War Directorate of the War Office states that subsequent scrutiny has shown discrepancies; and it is now believed that possibly 26 of the 717 Italians embarked on the ARANDORA STAR may not in fact have been on the Category "A" list. The Directorate also suggested that it is possible that some impersonation may have taken place.

Extract from Lord Snell’s conclusions of his Summary of the SS Arandora Star Inquiry, 1940. Catalogue reference: HO 213/1722

After the vessel was lost, the question of whether to deport internees was again brought to War Cabinet on 3 July. It was agreed that the following would be exempt from deportation: Men required for war production, men interned in error, and married men with wives and children upon whom special hardship would be imposed on separation.

Despite this, only one day after the Arandora Star's tragic sinking, 400 single Italians (that weren't among the 1,500 Category A internees) were sent to Canada on HMS Ettrick, along with 2,600 other internees. A further 1,838 would be deported to Canada on MS Sobrieski, which set sail on 7 July.

The 'inhumane' Dunera

Having survived the horrors of the Arandora Star’s destruction, 351 Germans and 200 Italians were selected to go on what would be the last ship to deport internees, HMT Dunera. It set sail on 10 July with 2,542 internees, though it was not bound for Canada. Instead it had a two-month journey to Australia.

Jewish refugees and Nazi sympathisers aboard were classified simply as Germans, and not segregated. This caused resentment and conflict on the journey.

The ship had a maximum capacity of 1,500 – including crew – and the resultant conditions have been described as ‘inhumane’. The deportees were also subjected to ill-treatment and theft by the 309 poorly trained British guards on board. Luggage was confiscated and thrown overboard. On deck, the internees were kept behind barbed wire, and the ship narrowly avoided two torpedo attacks.

Starboard view of the Dunera. Image credit: Australian War Memorial

On arrival in Sydney, the first Australian on board was medical army officer Alan Frost. He was appalled and his subsequent report led to the court martial of the army officer-in-charge, Lieutenant-Colonel William Scott.

Shifting public opinion

The sinking of the Arandora Star and the mistreatment on those on board the Dunera swayed public sympathy towards foreign internees. The government was moved too, authorising the release of 1,687 in August 1940. Not long after, the Under-Secretary of the Home Office, Osbert Peake, published a White Paper called Civilian Internees of Enemy Nationality, identifying categories of internees who could be eligible for release. By October about 5,000 Germans, Austrians and Italians had been released.

That number stood at 8,000 by December, leaving some 19,000 foreign citizens still interned in camps in Britain, Canada and Australia. Of those released, 1,273 were men who applied to join the Pioneer Corps. They would be joined by internees in Canada and Australia.

By August 1941, the number of internees released had risen to 17,500, and by 1942 fewer than 5,000 remained, mainly ardent Nazis and Fascists, on the Isle of Man. The National Archives houses lists of internees in these camps, including papers from their repatriation in 1945.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Summary of the Arandora Star Inquiry

- Date

- 1940

-

- Title

- Admiralty photographs of SS Arandora Star

- Date

- 1940

-

- Title

- Home Office index of foreign citizens considered for internment

- Date

- 1939–1947

-

- Title

- Publicity photographs of internment camps on the Isle of Man

- Date

- 1943–1945

-

- Title

- File on treatment of internees aboard the Dunera

- Date

- 1941