The Bethnal Green Tube shelter disaster

The UK suffered heavy bombing by the German air force from September 1940 to May 1941, a time known as the Blitz. By 1943 the worst seemed to be over, but on one tragic night that March in East London, hundreds of people were crushed together in a public air raid shelter and 173 lost their lives.

Preparing for air raids

For citizens of UK ports, cities and industrial centres during the Second World War, the danger of death or injury from bombs dropped by the German air force was a burden they had to bear, along with rationing and the absence of family members serving in the military.

Planning for the defence of the population against air raids had begun well before the outbreak of the conflict. The expectation was that precautions could be taken to mitigate the effects of shrapnel and debris on civilians, even if they couldn’t be protected from a direct hit.

Sir John Anderson, Minister for Home Security from 1939–1940, had commissioned the design of a domestic shelter that was issued free to families on low incomes – although they had to have a garden to put it in. Around 1.5 million Anderson shelters were distributed before war was declared in September 1939, and a further two million afterwards.

The Anderson shelter could be set down into the ground and covered over with earth. For those without outside space, a crate-like Morrison shelter could be used indoors during raids and perhaps as a worksurface or table at other times.

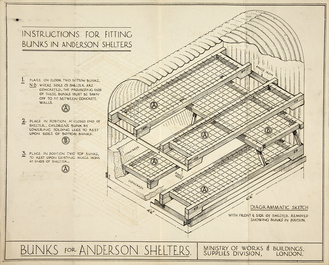

Instructions for fitting bunks in Anderson shelters. Catalogue reference: HO 287/783

Not everybody had the space for domestic shelters, and even those that did needed alternative shelter when they weren’t at home.

The 1939 Civil Defence Act stipulated that employers of more than 50 people in factories, mines and commercial premises had to provide shelters. Councils were given powers to requisition suitable buildings – such as those with large basements – to convert them into public shelters.

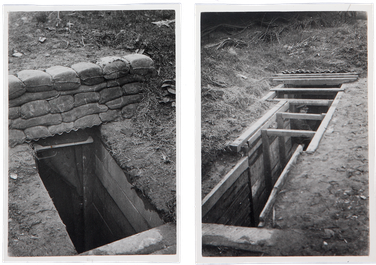

They also built ‘trench shelters’ in parks and other open spaces for people to use when they couldn’t get home during an air raid. The trenches were reinforced with metal and wooden props and covered with sandbags.

Home Office photographs of trench shelters, taken between 1935 and 1938. Catalogue reference: HO 45/17588

Using the Tube stations

In London, there seemed to be a series of readily available public shelters: the network of tunnels belonging to the London Underground, known as the Tube. Tube stations had already been used as shelters during the First World War. But when Sir John Anderson announced his Shelter policy to the House on 20 April 1939, the use of the Underground network was discouraged.

The government was concerned that large numbers of people crowding into the stations and tunnels without sanitation or suitable ventilation could spread disease, and possibly discontent. People sheltering in stations might disrupt the use of the trains by commuters and troops, and bombing could cause leaks from sewers and gas mains which would make the tunnels unsafe.

Initially, entrances to stations were blocked once air raids began, but very quickly the authorities relented and from 4pm people were allowed to start settling down for the evening on the platforms.

Londoners sheltering on escalators in the Tube, 1940. Image: IWM (HU 94168)

Committees were organised amongst the ‘shelterers’ to create some order and regulation. Chemical toilets were provided along with first aid and canteen facilities, and in some stations, bunks were fitted.

With trains running till 10.30pm, passengers still needed space to come and go, so white lines were painted along the length of platforms between the wall and the platform edge. The shelterers stayed behind the line, leaving room for the passengers until the trains stopped running, after which they could spread out over the rest of the platform.

The train had its windows covered with opaque or black-out material, and when it stopped at a station and the doors opened from the centre the effect was remarkably like that of a stage when the curtains are raised.

Sidney Toy, an architect, describing Oval station in November 1940

Once the electricity to the tracks was turned off, people slept between them, as well as on the stationary escalators.

Constructing deep shelters

In November 1940, the government authorised the construction of eight deep, bomb-proof shelters within the London Underground. These were at Belsize Park, Camden Town, Chancery Lane, Clapham, Clapham Common, Clapham North, Goodge Street and Stockwell.

The shelters were all 30 metres deep and 400 metres long, with each one designed to accommodate 8,000 people. They had upper and lower levels and were sub-divided into smaller units named after historic British naval commanders.

Goodge Street deep tunnel shelter, taken between 1942 and 1945. Catalogue reference: HO 197/47

The intense period of bombing known as the Blitz ended in 1941, before the deep shelters were ready, so they were repurposed by the military for storage and accommodation. However, after D-Day on 6 June 1944, when Germany began using V1 flying bombs and V2 rockets, the civilian population began to use the deep shelters for their original purpose.

Dancing and a singalong in a London Underground deep shelter, 1944. Catalogue reference: HO 207/386

Bethnal Green tube station in East London was still under construction when the war began, but enough work had been done for it to be used as an air raid shelter. It was situated right next to the Salmon & Ball pub, and so was known as both as the Salmon & Ball and the Bethnal Green tube shelter. Despite only having a single, narrow entrance it was one of the biggest shelters in London, and accounted for 60% of the available shelter in the area.

The entrances to tube stations would usually have been down steps which were directly open to the street, but in order to prevent light escaping during the blackout, station entrances were enclosed under temporary structures. At the Bethnal Green shelter the entrance to the enclosure was at 45 degrees to the station steps, making it slightly wider than the stairway it led to.

The entrance to Bethnal Green shelter as it was in 1943. Image: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

The entrance was down a flight of 19 steps to a landing, where passengers would turn right and go down seven more steps to what would have been the ticket hall (if work on the station had been finished). After this they would walk down two stationary escalators to the platforms.

Wednesday 3 March 1943

By 1943 the regularity of air raids had diminished, but people were cautious about reprisals following British aerial attacks on Germany. On Monday 1 March the Allies had carried out bombing raids on Berlin, so when the sirens sounded on Wednesday evening at 8.17pm, people began to head for shelter.

In Bethnal Green, patrons at nearby cinemas left to make their way to the Tube station, and at the same time three buses stopped at the station entrance so the passengers could get to safety.

Although people were moving in an orderly fashion, they became anxious when they heard unfamiliar explosive sounds. Being used to hearing the whine or drone of bombs falling before an explosion, the unfamiliar noise caused alarm. People thought a new kind of bomb was being dropped.

Witnesses saw a woman with a young child fall near the bottom of the first flight of steps. A man next to her also fell, and with the poor light and the volume of people following behind unaware that someone had fallen, in just a few seconds around 300 people had fallen on top of each other. Unable to move, many were being crushed.

Transcript

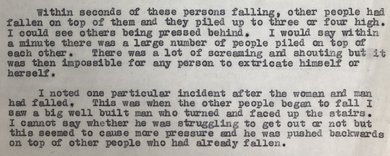

Within seconds of these persons falling, other people had fallen on top of them and they piled up to three or four high. I could see others being pressed behind. I would say within a minute there was a large number of people piled on top of each other. There was a lot of screaming and shouting but it was then impossible for any person to extricate himself or herself.

I noted one particular incident after the woman and man had falled. This was when the other people began to fall I saw a big well built man who turned and faced up the stairs. I cannot say whether he was struggling to get out or not but this seemed to cause more pressure and he was pushed backwards on top of other people who had already fallen.

Within seconds of these persons falling, other people had fallen on top of them and they piled up to three or four high. I could see others being pressed behind. I would say within a minute there was a large number of people piled on top of each other. There was a lot of screaming and shouting but it was then impossible for any person to extricate himself or herself.

I noted one particular incident after the woman and man had falled. This was when the other people began to fall I saw a big well built man who turned and faced up the stairs. I cannot say whether he was struggling to get out or not but this seemed to cause more pressure and he was pushed backwards on top of other people who had already fallen.

Extract from a statement by witness Walter Stedman. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/1942

The situation developed into a tragedy in a matter of seconds, as people were unable to breathe with the weight of others on top of them. Despite the best efforts of those attending the scene, it took three hours to release everyone caught in the crush.

As bodies were removed the estimates of the numbers killed and injured grew. The final toll revealed 173 dead and 60 in need of hospital treatment. Of those killed, 27 were men, 84 were women and 62 were children under 16.

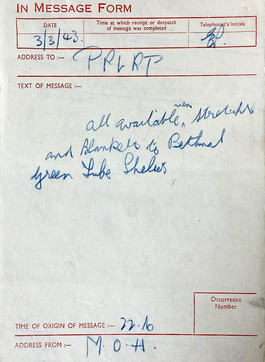

A Home Office file containing material relating to the disaster includes message slips from the ARP (Air Raid Precautions) Control Centre. The first, timed at 21.09 on 3 March, shows two ‘Light Rescue Parties’ being despatched to the shelter. Another, timed just over an hour later, says ‘all available men, stretchers and blankets to Bethnal Green Tube Shelter’.

ARP message form dated 3 March 1943, timed at 22.16. Catalogue reference: HO 205/228

People that had already entered the shelter were unaware of the events unfolding above them. Witnesses said that even those immediately in front of those that fell didn’t realise what had happened, as they simply carried on their way into the shelter without looking back. By the time the shelterers emerged in the morning, the stairway had been cleared and washed down.

Fifty years on from the disaster, a plaque was erected on the staircase to Bethnal Green station where the tragedy occurred. The words on the plaque describe the event as the ‘worst civilian disaster of the Second World War.’

The memorial plaque at the entrance to Bethnal Green Tube station. Image: Sarah Castagnetti

Read how the full details of the disaster became public, and about other efforts to memorialise the tragedy, in our article about Bringing the Bethnal Green disaster to light.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Home Office records on air raid shelters for the civilian population

- Date

- 1935–1938

-

- Title

- Photos of the deep shelter at Goodge Street Underground station

- Date

- 1942–1945

-

- Title

- Reports on welfare and general conditions in public shelters

- Date

- 1940–1945

-

- Title

- Report on the Bethnal Green Tube Station shelter disaster

- Date

- 1943