Policing sex in public toilets in 1930s London

Records at The National Archives reveal how attempts to police cottaging in 1930s London proved difficult – both for those suspected, and for officers tasked with enforcing the law.

Important information

This article references attempts to suppress activities by gay and bisexual men, as well as institutional homophobia.

‘A certain act of gross indecency’

It’s the summer of 1932. Lambeth Police Court. Two men sit in front of the Magistrates of the Police Courts accused of having committed a ‘certain act of gross indecency with each other’.

This is the story told by CRIM 1/617, a deposition to the Central Criminal Court – widely known as the Old Bailey – kept at The National Archives.

-

- Title

- Central Criminal Court: Charges against Charles Pearson and Ralph Byrne

- Date

- 13 September 1932

Presenting the case, the first witness produces a plan which he has prepared ‘of the public urinal in Popes Road, Brixton’, and explains that standing on the base of the lamppost (seven inches from the ground), it is possible see into ‘the urinal above the filigree work below the roof.’ A number of photographs were also presented.

Police photograph of the public toilet in Brixton, 1932. Catalogue reference: CRIM 1/617

The second witness, policeman K, specifies he was on duty in ‘plain clothes’ with a colleague, policeman H, when he went into the toilet to relieve himself and saw two men inside, alone.

‘They were not urinating,’ he says. ‘They were talking.’

Finding that behaviour suspicious, he suggested keeping observation. One of the two men in the toilet left, walked around the block and went back in. The two policemen got close and climbed the lamppost to look inside.

In a matter of seconds, his colleague slipped from the lamppost, making a noise which alarmed the two men. However, in those few moments, policeman K says,

[I] could see what each man did. Each was exposed’.

Policeman K, on what he observed in the public toilet

Back at Brixton Police Station, at the end of cross examination, policeman H comments that: ‘I have not been looking out for this sort of thing before. The men did not make everything easy for discovery.’

He did not know the word we might use for this behaviour today – cottaging – accepted since the 1960s, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, to mean 'The action of a man engaging in or soliciting sex with another man in a public toilet'. But this activity was to raise a number of revealing questions for the Metropolitan Police over the coming years.

Prevention or surveillance?

Policeman H’s comment, reported in the criminal record, suggests that catching men involved in ‘indecent acts’ was not an easy task. It required time, attention and strategy.

The policemen could have walked away at any point – after all, the two men in the toilets weren’t committing any crime when first seen. The suspicion that they might be about to commit one, and the willingness of the police to enforce the law, meant that surveillance was employed until it was possible to catch them in the act.

Police photograph of the interior of the public toilet in Brixton, 1932. Catalogue reference: CRIM 1/617

CRIM 1/617 shows that the line between preventing a crime and surveilling people can be very fine. In some cases it was also non-existent, for example when policemen acted as agents provocateur, enticing men through deceptive means to respond to sexual invitations – so they could catch them red-handed. Evidence of such actions can be found among records at The National Archives.

In this context of moral surveillance, strategies of resistance developed. Secret knowledge circulated underground and by word of mouth, sometimes even in plain sight. This is the case with the book For Your Convenience, published in 1937 by the British writer Thomas Burke, under the pseudonym Paul Pry.

For Your Convenience, disguised as a satire on where to find public toilets in London if one were to be ‘walking through Wigmore street after three cups of tea’, provided useful information (and a map!) on the types and the safest cottaging locations in central London – to those who were able to read between the lines.

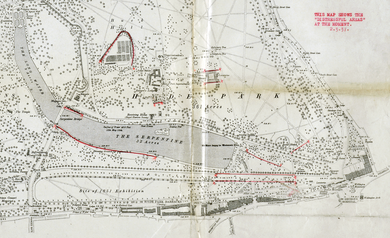

Although entertaining, the book was a radical and risky publication, and the police might have become aware of it. Burke wasn't the only person to create a cottaging map at the time – the Royal Parks Division of the Department of Works made this one, of so-called 'distressful areas' in Hyde Park, in 1937:

Map of areas of immorality in Hyde Park in 1937. Catalogue reference: WORK 16/543

Issues defining and enforcing

Correspondence in a Metropolitan Police file called MEPO 3/989 dates back to 1938, and it refers to an order in the police Instruction Book from 1923 (but originally included in 1872) that stated:

Persons frequenting urinals supposed for an improper purpose should be cautioned. If they persist and commit an offence they should be arrested. (See par. 140).

Police Instruction Book, 1923

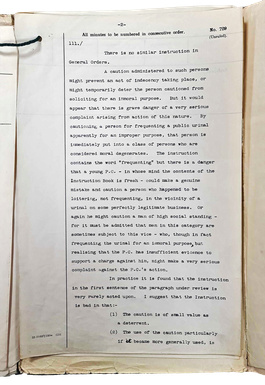

The correspondence in 1938 centres around the wording of this instruction, and the procedure to follow when men are caught cottaging. Both are deemed unclear and problematic. In particular, concerns are raised around the words ‘frequenting’ and ‘cautioned’.

Partial transcript

A caution administered to such persons might prevent an act of indecency taking place, or might temporarily deter the person cautioned from soliciting for an immoral purpose. But it would appear that there is grave danger of a very serious complaint arising from action of this nature. By cautioning a person for frequenting a public urinal apparently for an improper purpose, that person is immediately put into a class of persons who are considered moral degenerates. The instruction contains the word "frequenting but there is a danger that a young P.C. – in whose mind the contents of the Instruction Book is fresh – could make a genuine mistake and caution a person who happened to be loitering, not frequenting, in the vicinity of a urinal on some perfectly legitimate business. Or again he might caution a man of high social standing – for it must be admitted that men in this category are sometimes subject to this vice – who, though in fact frequenting the urinal for an immoral purpose, but realising that the P.C. has insufficient evidence to support a charge against him, might make a very serious complaint against the P.C.'s action.

In practice it is found that the instruction in the first sentence of the paragraph under review is very rarely acted upon. I suggest that the Instruction is bad in that:-

(1) The caution is of small value as a deterrent.

(2) The use of the caution particularly if it became more generally used, is [...]

A caution administered to such persons might prevent an act of indecency taking place, or might temporarily deter the person cautioned from soliciting for an immoral purpose. But it would appear that there is grave danger of a very serious complaint arising from action of this nature. By cautioning a person for frequenting a public urinal apparently for an improper purpose, that person is immediately put into a class of persons who are considered moral degenerates. The instruction contains the word "frequenting but there is a danger that a young P.C. – in whose mind the contents of the Instruction Book is fresh – could make a genuine mistake and caution a person who happened to be loitering, not frequenting, in the vicinity of a urinal on some perfectly legitimate business. Or again he might caution a man of high social standing – for it must be admitted that men in this category are sometimes subject to this vice – who, though in fact frequenting the urinal for an immoral purpose, but realising that the P.C. has insufficient evidence to support a charge against him, might make a very serious complaint against the P.C.'s action.

In practice it is found that the instruction in the first sentence of the paragraph under review is very rarely acted upon. I suggest that the Instruction is bad in that:-

(1) The caution is of small value as a deterrent.

(2) The use of the caution particularly if it became more generally used, is [...]

Metropolitan Police correspondence on amending the police Instruction Book, 1938. Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/989

Firstly, ‘frequenting’ is not well defined. As one of the correspondents suggests:

... there is a danger that a young P.C. – in whose mind the contents of the Instruction Book is fresh – could make a genuine mistake and caution a person who happened to be loitering, not frequenting, in the vicinity of a urinal on some perfectly legitimate business.

Secondly, ‘cautioning’ can be a risky tactic. While it could prevent an act of indecency taking place, it might also pose a greater risk (according to the correspondent): a serious complaint against the police.

A person cautioned for frequenting a public urinal apparently for an improper purpose is, according to the correspondence, immediately considered a ‘moral degenerate’. But what if this is a man of higher social status? A man with power? What if there isn’t enough evidence to support the allegation and a complaint against the policeman is made? Such complaints had happened before – on 28 and 30 July 1937, in St John’s Wood and in West London.

The debate goes on and on, and suggestions for rephrasing are made. Unconvincing amendments are approved and overwritten. New proposals are made, each one becoming more convoluted than the previous one.

The correspondence ends with the last proposal:

If police observe persons frequenting urinals apparently for improper purposes, they should report the facts to their S.D. Inspector so that the advisability of having observation kept upon such persons can be considered. If a definite offence is observed offenders should be arrested (see para 140).

Fear and uncertainty – on all sides

Two considerations emerge when reading this Metropolitan Police correspondence against the Central Criminal Court papers, and in light of the general moral surveillance described above.

Firstly, although the law punished ‘indecent acts’, there was a lot of uncertainty around how to enforce it. The police force itself, as MEPO 3/989 shows, was unclear in 1938 on how to formulate guidelines on what to do in the context of sexual activity in public toilets. In many cases it was down to the individual policeman to decide how to act, and his subjective interpretation of the circumstances might be based on personal moral values.

Secondly, the fear of retaliation from people of higher social status seemed to be a key reason the guidelines were reviewed and revised in the first place, rather than questioning the legislation itself. This showing that class, as well as moral values, played a role in the enactment of the law.

As such, the liminal space of the public toilets becomes even more interesting. Not only does it sit between private and public, freedom and punishment, but also it is where power and fear from both sides – the police and men looking for sexual intercourse – ultimately conflict.

Read more

Helen Smith, Masculinity, Class and Same-Sex Desire in Industrial England, 1895-1957, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957, University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Paul Pry, For Your Convenience, Hardback, 1937.