Hidden intentions

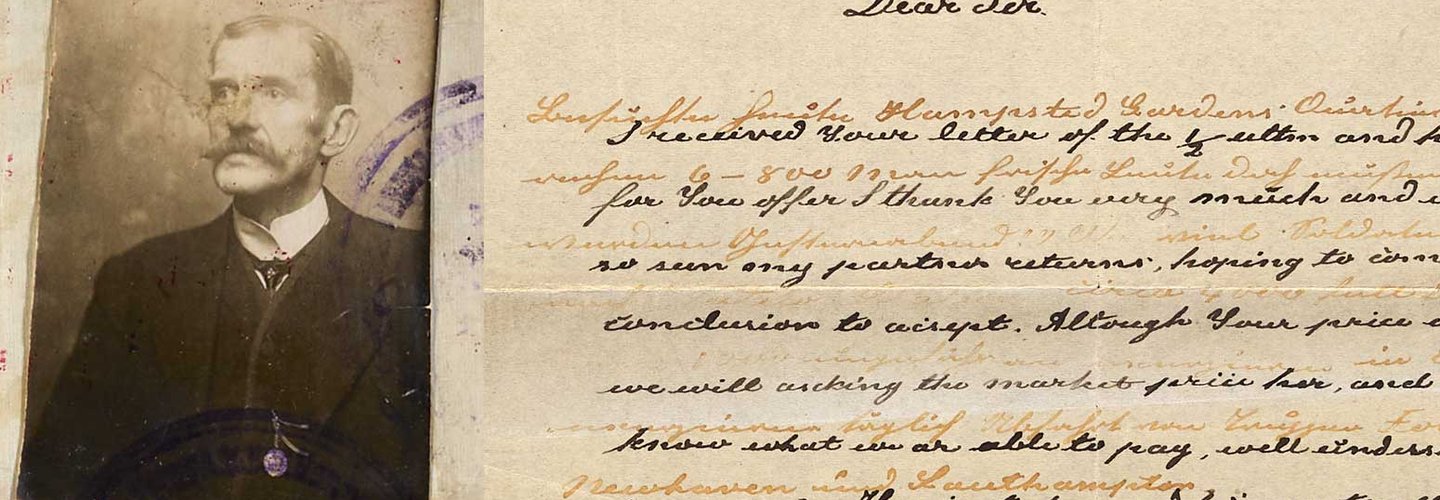

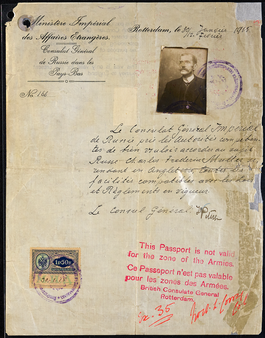

Karl Muller was among a crowd of refugees from Belgium who landed at Hull, East Yorkshire, on 10 January 1915. He had a Russian passport and his occupation was given as ‘Ship broker’, arranging for the transport of cargo. His passport photograph shows that he sported a classic ‘walrus’ moustache.

Karl Muller's passport. Catalogue reference: CRIM 1/683 (3)

Muller was not in fact Russian – he was German. And only a few weeks after he arrived in Britain, he posted several letters to an address in Rotterdam, under the fake name ‘L. Cohen’.

Why the deception? Nothing appeared suspicious in these letters at all. As with Muller himself, however, there was more to them than met the eye.

The postal censorship office

Britain had been wary of foreign agents operating within its shores in the run up to the First World War, and the Secret Service Bureau – now commonly known as MI5 – had been established in 1909. It had found great success rounding up German spies when the conflict broke out. Nonetheless, it was vigilant that enemy operatives might attempt to send reports on Britain’s military and economy back home.

By the end of the war, over 4,000 workers – mostly women – were employed by the government to examine the mail for anything suspicious. It ran to millions of pieces every month. The postal censorship office monitored letters and telegrams sent abroad, paying particular attention to post sent to ‘cover addresses’ that were known to be used by German intelligence.

The postal censorship department's testing laboratory in the First World War. Catalogue reference: KV 1/73

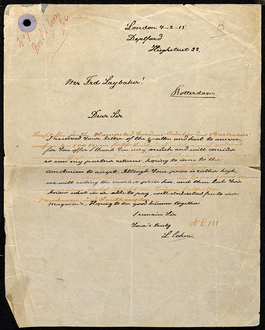

It was one of these special addresses that Muller – under the name ‘L. Cohen’ – had sent his letters to. Censorship office workers duly flagged them and gave them to an MI5 officer, who, recognising possible subterfuge, passed a warm, flat iron over each one. This revealed hidden messages in German, squeezed between the lines of otherwise innocuous writing.

Transcript

[This transcription attempts to capture what Muller wrote, including what appear to be errors, but it may not be fully accurate]

London 4-2-15

Deptford

Highstreet 22.

Mr Fred Laybaker!

Rotterdam

Dear Sir,

I received your letter of the 1/2 ultm and hast to answer. For You offer I thank you very much and will consider so soon as my partner returns, hoping to come to the conclusion to acsept. Altough your price is rather high, we will ascking the market price here, and then beat you know what we are able to pay, well understud free to ouer magazin’s.. Hoping to du good business together

I remain Sir

Your’s truly

L Cohen.

[This transcription attempts to capture what Muller wrote, including what appear to be errors, but it may not be fully accurate]

London 4-2-15

Deptford

Highstreet 22.

Mr Fred Laybaker!

Rotterdam

Dear Sir,

I received your letter of the 1/2 ultm and hast to answer. For You offer I thank you very much and will consider so soon as my partner returns, hoping to come to the conclusion to acsept. Altough your price is rather high, we will ascking the market price here, and then beat you know what we are able to pay, well understud free to ouer magazin’s.. Hoping to du good business together

I remain Sir

Your’s truly

L Cohen.

Secret writing revealed between lines of one of the letters. Muller’s identity code, A E III, can be seen near the signature. Catalogue reference: CRIM 1/683

Translating them revealed that they were little nuggets of military intelligence, though not particularly high grade in nature, such as, ‘In Epsom 10000 men were drilling daily. Troops depart from Folkestone, Newhaven and Southampton’.

Tracking down the source

The address of ‘L. Cohen’ was given as 22 Deptford High Street. Enquiries by Scotland Yard proved that there was no one called Cohen at this address, so detectives decided to explore the Deptford connection further. On 24 February this led them to the door of John Hahn, a German-born baker with British citizenship, who lived at his premises at 111 Deptford High Street.

Inspector George Riley and other officers arrived to find Hahn was out, and spoke to Mrs Hahn, who told them that her husband had been associating with a Russian called Karl Muller. They then proceeded to search the Hahns’ house and found a lemon which appeared to be pierced at the top, along with a pen nib and some writings captured on blotting paper.

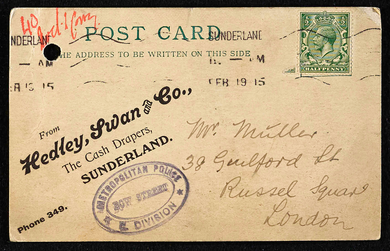

The police waited many hours and arrested John Hahn when he arrived. From exchanges with him, they confirmed Karl Muller’s address: 38 Guilford Street, off Russell Square in Bloomsbury.

Postcard sent to Karl Muller at Guilford Street. Catalogue reference: CRIM 1/683

The next day Inspector Edward Parker and other officers arrested Muller at his lodgings. Parker found a lemon in the suspect’s overcoat pocket, as well as three pieces of lemon wrapped in cotton wool in a dressing table drawer. When the Inspector Parker asked Muller what the lemon was for, he pointed to his mouth and said ‘My teeth’.

The police were not persuaded that lemon juice was a suitable method for cleaning teeth!

The giveaway fruit

The discovery of lemons, in itself, was cause for suspicion. Lemon juice had been used for centuries as a form of 'invisible ink', since it cannot be seen on paper until it carbonises when heated. Other methods were available by the time of the First World War, but Muller had not realised the risks involved with using such a time-honoured approach.

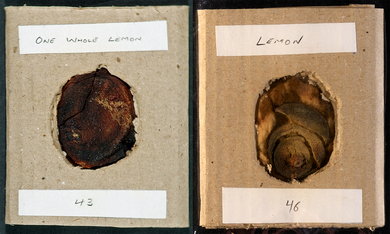

The evidence found at the Muller and Hahn premises was thoroughly tested using forensic techniques, and cellular matter from lemons was detected on the pen nibs the police had seized. Incredibly, since they were used in court, both the whole lemon and the segmented one survive in the holdings of The National Archives – blackened and shrivelled, but significant items nonetheless.

Left: The lemon found in Muller’s coat pocket. Right: Pieces of lemon found with cotton wool in a drawer in Muller’s lodgings. Catalogue references: CRIM 1/683 and 1/684

A terrible price

Muller was put on trial at the Central Criminal Court on 14 April. Charles Mitchell, a specialist in the chemistry of inks, gave testimony about how the cellular matter on the nib of a pen corresponded with the cellular matter of the lemon exhibited.

Hahn was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude. Muller was found guilty of espionage and sentenced to be shot. Like other German spies before him, he was executed by firing squad at the Tower of London.

When his time came he is said to have walked along the line of men who were about to kill him, solemnly shaking each one by the hand, before his eyes were bound and he bravely faced the firing squad on 23 June 1915.

M: MI5’s First Spymaster, Andrew Cook (Tempus, 2006), p. 263

The trial had been held in secret rather than in public. This enabled MI5 to continue, for several months, to send fabricated reports from Muller to German intelligence in Antwerp, which responded by sending payment for his services and by making requests for further information.

The money sent to Muller enabled MI5 to purchase a car, a two-seater Morris which they named the ‘Muller’. This deception was, in some ways, a forerunner of the highly successful Double Cross system employed by MI5 during the Second World War. And once Muller's true fate became known, it served as a dire warning to others intending to spy in Britain while at war.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Evidence against Karl Muller at the Central Criminal Court

- Date

- 14 April 1915

-

- Title

- Further evidence against Karl Muller at the Central Criminal Court

- Date

- 14 April 1915