Important information

This story includes a document that uses a racist term for the word 'Japanese'. Original language is preserved here to accurately represent our records and to help us fully understand the past.

Early life

Born in February 1936 in Shanghai, China, Judy was a liver and white Pointer dog. She was one of seven puppies born to a dog owned by a British couple, in a dog kennel used by Europeans living in the city. She had originally been called Shudi, but this was anglicised to Judy in the first six months of her life.

Towards the end of 1936, the Royal Navy ship HMS Gnat, based in China, was looking for a ship’s mascot and Judy was purchased from the kennel and duly presented to the ship’s crew. Dogs were used by the military for several reasons. Some were trained for specific tasks such as mine hunting, while others were taken on as mascots to help with pest control and morale. Once onboard Judy was looked after by the ship’s butcher, who was given the title 'Keeper of the Ship’s Dog'.

In mid-1939, some of the Gnat’s crew transferred to HMS Grasshopper and Judy went with them. It was this ship that Judy was on at the outbreak of war against Japan in December 1941, following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Judy and a sailor on the deck of HMS Grasshopper. From the Imperial War Museum collection © IWM HU 43990

The early months of the war

In early 1942, as Allied forces were in full retreat from the advancing Japanese forces, HMS Grasshopper supported the withdrawals from Malaya into Singapore. Shortly before the latter surrendered, Grasshopper began to make its way to the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia). On the journey it was bombed by Japanese aircraft and the order was given to abandon ship.

The crew were briefly marooned on an uninhabited island without water, but were saved by Judy, who was able to locate a freshwater spring to drink from. They were then picked up and taken to Singkep Island to continue their evacuation. From here, they travelled by boat to Sumatra, where they hoped to meet with other evacuating Allied forces. Making their way through the jungle, Judy was attacked by an alligator, suffering a two-inch cut over her left eye. By the time they made it to their destination Allied forces had already left, and the surviving crew – including Judy – were taken as prisoners of war (POW) by Japanese forces on 18 March.

HMS Grasshopper. From the Imperial War Museum collection © IWM HU 43993

Prisoner of war at Medan

Within days, the prisoners of war arrived at Gloegoer Camp in Madan in northern Sumatra. Here Judy was initially hidden from the camp's guards. By August 1942 she had met Leading Aircraftsman Frank Williams, who shared his daily rice ration with her. He recalled years later:

I remember thinking what on earth is a beautiful English Pointer like this doing here, with no one to care for her. I realised that even though she was thin, she was a survivor.

After persuasion from Frank, Judy was eventually registered as a POW by the Japanese guards and given the number '81A Gloegoer Medan'. She was the only dog officially recognised as a prisoner of war in the Second World War. Through this status Judy was provided food rations and treated as any other prisoner of war. At the camp she is said to have fought off snakes and scorpions, would go hunting for food, and would distract the guards of the camp when required. Her companionship was also a vital source of support for POWs.

In the middle of 1944, the POWs at Medan were scheduled to move to Singapore and, though dogs were not permitted on the ship, Frank smuggled Judy aboard in a rice sack. Here she managed to lie still for three hours avoiding detection. They travelled on the Haugiku Maru, which was what was known as a ‘hell ship’ because of the terrible conditions found on the vessel.

With 700 POWs on board, the ship was torpedoed, resulting in the deaths of over 500 of the ship’s passengers. Frank was one of those survivors and had pushed Judy out of a porthole to try and save her. While in the water, Judy attempted to assist several non-swimmers and wounded men to safety.

Prisoner of war at Sumatra

After being recaptured and imprisoned, initially Frank was unsure as to whether Judy had survived. But, after a month of uncertainty he was reunited with his dog, who had once again been successfully hidden from Japanese guards. He later told a newspaper:

I couldn’t believe my eyes. As I entered the camp, a scraggy dog hit me square between the shoulders and knocked me over! I’d never been so glad to see the old girl. And I think she felt the same!

Frank and Judy, along with their fellow POWs, then spent the next year cutting through the Sumatran jungle, opening a route for a new railway. Conditions were once again brutal – food was scarce and illness and disease common.

In August 1945, Japanese forces finally surrendered, and POWs camps were liberated. Frank made it his mission to ensure that Judy could return home with him.

After the war

Once more, Judy was smuggled on board a ship. This time the troopship Antenor where she was hidden for the majority of the six-week journey to the UK. She then spent six months in quarantine in London before being reunited with Frank, who was permitted to take her with him on his new Royal Air Force duties in the UK.

Judy’s story came to the attention of Maria Dickin (1870–1951), the founder of the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA). She had instituted the Dickin Medal to recognise the actions of animals in wartime.

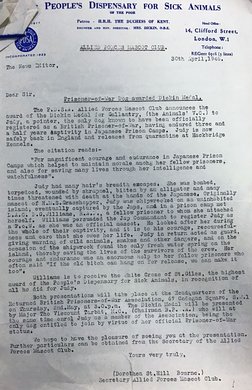

On 30 April 1946, the PDSA announced that Judy was to be awarded the Dickin Medal for Gallantry, referred to as the ‘Animals’ Victoria Cross’ in the letter of confirmation. The citation for her medal, today in The National Archives’ collection of Air Ministry and Royal Air Force records, reads:

For magnificent courage and endurance in Japanese Prison Camps which helped to maintain morale among her fellow prisoners, and also for saving many lives through her intelligence and watchfulness.

Catalogue reference: AIR 2/5036

Partial transcript

The P.D.S.A.... announces the award of the Dickin Medal for Gallantry, (the Animals’ V.C.) to Judy, a pointer, the only dog known to have been officially registered as a British prisoner of war, having endured three and a half years captivity in Japanese Prison Camps. Judy is now safely back in England and released from quarantine at Hackbridge Kennels.

For magnificent courage and endurance in Japanese Prison Camps which helped to maintain morale among her fellow prisoners, and also for saving many lives through her intelligence and watchfulness.

Judy had many hair’s breadth escapes. She was bombed, torpedoed, wounded by shrapnel, bitten by an alligator and many times threatened with death at the hands of the Japanese. Originally mascot of H.M.S. Grasshopper, Judy was shipwrecked on an uninhabited island, eventually captured by the Japs, and in a prison camp met L.A.C. F.G. Williams, R.A.F., a fellow prisoner to whom she attached herself. Williams persuaded the Jap Commandant to register Judy as a P.o.W. as she was an official mascot. He looked after her during the whole of their captivity, and it is to his courage, resourcefulness and care that she owes her life. Judy in return acted as guard, giving warning of wild animals, snakes and other dangers, and on the occasion of the shipwreck found the only fresh water spring on the island, thereby saving the lives of the survivors of the crew. Her courage and endurance was an enormous help to her fellow prisoners.

The P.D.S.A.... announces the award of the Dickin Medal for Gallantry, (the Animals’ V.C.) to Judy, a pointer, the only dog known to have been officially registered as a British prisoner of war, having endured three and a half years captivity in Japanese Prison Camps. Judy is now safely back in England and released from quarantine at Hackbridge Kennels.

For magnificent courage and endurance in Japanese Prison Camps which helped to maintain morale among her fellow prisoners, and also for saving many lives through her intelligence and watchfulness.

Judy had many hair’s breadth escapes. She was bombed, torpedoed, wounded by shrapnel, bitten by an alligator and many times threatened with death at the hands of the Japanese. Originally mascot of H.M.S. Grasshopper, Judy was shipwrecked on an uninhabited island, eventually captured by the Japs, and in a prison camp met L.A.C. F.G. Williams, R.A.F., a fellow prisoner to whom she attached herself. Williams persuaded the Jap Commandant to register Judy as a P.o.W. as she was an official mascot. He looked after her during the whole of their captivity, and it is to his courage, resourcefulness and care that she owes her life. Judy in return acted as guard, giving warning of wild animals, snakes and other dangers, and on the occasion of the shipwreck found the only fresh water spring on the island, thereby saving the lives of the survivors of the crew. Her courage and endurance was an enormous help to her fellow prisoners.

Confirmation of Judy's Dickin Medal. Catalogue reference: AIR 2/5036

-

- Title

- Awards of Dickin Medal for gallantry

- Date

- 1943–1946

The letter also confirmed that Frank was to receive the White Cross of St Giles, the highest award given by the PDSA, in recognition of the care that he gave for Judy.

Judy and Frank being awarded the Dickin Medal, 2 May 1946. Credit: TopFoto

Later life

Judy and Frank stayed together in the years immediately after the war. They first lived in Portsmouth and then in Tanzania, where in 1948 Frank took on a British Government post. It was here two years later where Judy died, on 17 February 1950. She was buried here with an RAF jacket and Frank built a memorial stone in her honour that told her story.

Judy and Frank pictured at the Clifford Street London PDSA, 10 May 1948. Credit: TopFoto

In 2006, as part of an exhibition on animals in war, the Williams family bequeathed Judy’s Dickin Medal to the Imperial War Museum. Speaking at the presentation Frank’s wife Doris said:

Although I never knew Judy in life, she always felt like a member of our family who undoubtedly and repeatedly saved my husband’s life and that of his fellow prisoners during the war… her courage and devotion to duty will be remembered by generations to come.