Emily Capper and the 1934 Gresford Colliery disaster

On the morning of 22 September 1934, a deadly explosion ripped through the Gresford coal mine in North Wales, claiming over 260 lives. Our records tell the story of Emily Capper and her desperate campaign to recover the bodies of the victims, including that of her son.

Emily and William Capper

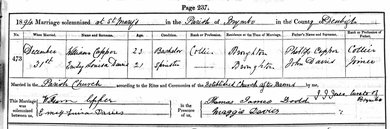

Emily Louisa Davies was born in 1873 in Brymbo, near the town of Wrexham, Denbighshire. In 1894, at the age of 21, she married William Capper in the parish Church of St Mary's. There were a number of coal mines in North Wales at this time, and both William and his father were listed as colliers in the marriage register.

Marriage register entry for Emily Louisa Davis and William Capper. Denbighshire Record Office, reference PD/10/1/5, courtesy of FindMyPast.

The couple had eight children between 1896 and 1915. Sadly, two died young: Fred at the age of five in 1903, and Ceridwen at three in 1918. By 1911 their eldest child Edith, aged 15, was working as a live-in domestic servant.

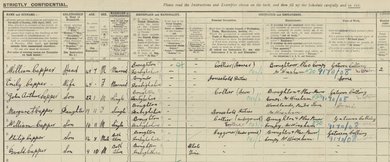

By 1921, the family of seven were living in Pentre Broughton, just outside Wrexham. The 1921 census shows William and three of his sons, John (22), William (16), and Philip (14), all working at the Gatewen Colliery. It was one of many mines in the area that had been producing coal since the second half of the 19th century.

1921 census entry showing Emily, William and their five children. Catalogue reference: RG 15/27684. Courtesy of FindMyPast

In 1911, a new, deep pit was opened at Gresford, and in 1923 another at Llay Main. In 1932 Gatewen closed, and by 1934 William senior had stopped working, while John had moved to the Gresford mine.

One of the largest in the area, Gresford employed over 2,000 miners and operated seven days a week. But in the 1930s, like other British coalfields, it was struggling financially. This resulted in high levels of unemployment among miners but also pressure on owners to increase output.

Wrexham AFC

Formed in 1864, Wrexham AFC was the local football team. On Saturday 22 September, Wrexham were due to play regional rivals Tranmere Rovers in an early-season clash. Wrexham had a loyal following among the Gresford miners, and that Friday, many worked through the night or swapped shifts so they could make the game.

The explosion and aftermath

At around 2am, an explosion, likely caused by a spark igniting with high levels of gas, ripped through the Dennis section of the mine causing a fire. Those closest to the explosion were killed instantly. Others quickly succumbed to carbon monoxide released by the blast. Six managed to escape, but 261 were killed.

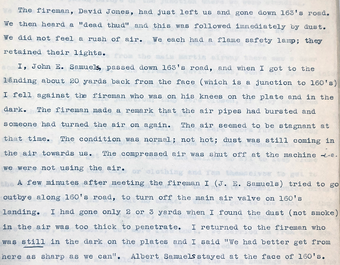

Transcript

The fireman, David Jones, had just left us and gone down the 163's road. We then heard a "dead thud" and this was followed immediately by dust. We did not feel a rush of air. We each had a flame safety lamp; they retained their lights.

I, John E. Samuels, passed down 163's road, and when I got to the landing about 20 yards back from the face (which is a junction to 160's) I fell against the fireman who was on his knees on the plate and in the dark. The fireman made a remark that the air pipes had bursted and someone had turned the air on again. The air seemed to be stagnant at that time. The condition was normal; not hot; dust was still coming in the air towards us. The compressed air was shut off at the machine i.e. we were not using the air.

A few minutes after meeting the fireman I (J. E. Samuels) tried to go outbye along 160's roads, to turn off the main air valve on 160's landing. I had gone only 2 or 3 yards when I found the dust (not smoke) in the air was too thick to penetrate. I returned to the fireman who was still in the dark on the plates and I said "We had better get from here as sharp as we can". Albert Samuels stayed at the face of 160's.

The fireman, David Jones, had just left us and gone down the 163's road. We then heard a "dead thud" and this was followed immediately by dust. We did not feel a rush of air. We each had a flame safety lamp; they retained their lights.

I, John E. Samuels, passed down 163's road, and when I got to the landing about 20 yards back from the face (which is a junction to 160's) I fell against the fireman who was on his knees on the plate and in the dark. The fireman made a remark that the air pipes had bursted and someone had turned the air on again. The air seemed to be stagnant at that time. The condition was normal; not hot; dust was still coming in the air towards us. The compressed air was shut off at the machine i.e. we were not using the air.

A few minutes after meeting the fireman I (J. E. Samuels) tried to go outbye along 160's roads, to turn off the main air valve on 160's landing. I had gone only 2 or 3 yards when I found the dust (not smoke) in the air was too thick to penetrate. I returned to the fireman who was still in the dark on the plates and I said "We had better get from here as sharp as we can". Albert Samuels stayed at the face of 160's.

Statement from survivor John Samuels. Catalogue reference: POWE 8/890

Within a few hours, volunteers entered the mine and managed to recover seven bodies. Later that morning the official rescue team went in. Tragically, three rescuers were killed by the carbon monoxide, bringing the death toll to 264. Two of their bodies were retrieved, but the third, John Lewis, would take six months to recover.

Emily's son, John, was one of the 261 caught in the explosion. As the news reached town, she and many others went to the pithead waiting in hope for loved ones to emerge. As the hours became days anxious families' worst fears became reality. The miners had not survived. The families' attention now turned to attempts to recover their loved ones so they could be given a proper burial.

Crowds gathered by the Gresford Colliery pit following news of the explosion, 28 September 1934. Photograph from the Wrexham Star reproduced by kind permission of Margaret Jones.

On 25 September, George Brown became the 265th victim of the disaster when he was hit by flying debris above ground caused by ongoing explosions within the mine.

Transcript

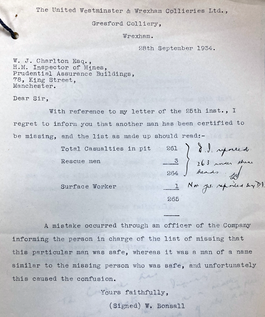

The United Westminster & Wrexham Collieries Ltd.,

Gresford Colliery,

Wrexham.

28 September 1934.

W. J. Charlton Esq.,

H.M. Inspector of Mines,

Prudential Assurance Buildings,

78, King Street,

Manchester.

Dear Sir,

With reference to my letter of the 25th inst., I regret to inform you that another man had been certified to be missing, and the list as made up should read:-

Total Casualties in pit: 261

Rescue men: 3

Total: 264

Surface Worker: 1

Total: 265

A mistake occurred through an officer of the Company informing the person in charge of the list of missing that this particular man was safe, whereas it was a man of a name similar to the missing person who was safe, and unfortunately this caused the confusion.

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) W. Bonsall

The United Westminster & Wrexham Collieries Ltd.,

Gresford Colliery,

Wrexham.

28 September 1934.

W. J. Charlton Esq.,

H.M. Inspector of Mines,

Prudential Assurance Buildings,

78, King Street,

Manchester.

Dear Sir,

With reference to my letter of the 25th inst., I regret to inform you that another man had been certified to be missing, and the list as made up should read:-

Total Casualties in pit: 261

Rescue men: 3

Total: 264

Surface Worker: 1

Total: 265

A mistake occurred through an officer of the Company informing the person in charge of the list of missing that this particular man was safe, whereas it was a man of a name similar to the missing person who was safe, and unfortunately this caused the confusion.

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) W. Bonsall

Letter from Gresford Colliery manager William Bonsall to H.M. Inspector of Mines, 28 September 1934. Catalogue reference: POWE 8/890

Letters at The National Archives

After weeks with no news, families like the Cappers began to worry their loved ones were being abandoned where they lay.

Files at The National Archives contain letters and petitions by the community asking the authorities to continue efforts to retrieve those killed. The Cappers wrote nine letters and raised two petitions.

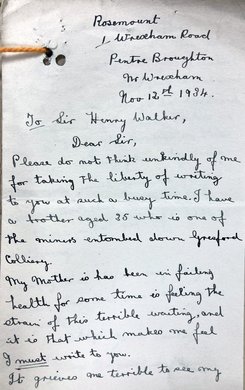

It was decided that Chief Inspector of Mines, Sir Henry Walker, would lead the official inquest into the disaster. It opened on 25 October 1934 in Church House, Wrexham. The next month, on 12 November, Emily's daughter Margaret wrote to Walker highlighting the 'terrible waiting' the family were going through.

My Mother [who] has been in failing health for some time is feeling the strain of this terrible waiting, and it is that which makes me feel I must write to you. It grieves me terrible to see my Mother and Father suffering terrible under this heavy burden they have to bear, and the thought of where their loved one is lying is unbearable. Could not an attempt be hastened to try and get those bodies in their proper resting place, by doing this you will give the only consolation there is to be given to those who are left behind suffering.

Margaret Capper

Partial transcript

Please do not think unkindly of me for taking the liberty of writing to you at such a busy time. I have a brother aged 35 who is one of the miners entombed down Gresford Colliery.

My Mother [who] has been in failing health for some time is feeling the strain of this terrible waiting, and it is that which makes me feel I must write to you.

It grieves me terrible to see my Mother and Father suffering terrible under this heavy burden they have to bear, and the thought of where their loved one is lying is unbearable. Could not an attempt be hastened to try and get those bodies in their proper resting place, by doing this you will give the only consolation there is to be given to those who are left behind suffering.

Please do not think unkindly of me for taking the liberty of writing to you at such a busy time. I have a brother aged 35 who is one of the miners entombed down Gresford Colliery.

My Mother [who] has been in failing health for some time is feeling the strain of this terrible waiting, and it is that which makes me feel I must write to you.

It grieves me terrible to see my Mother and Father suffering terrible under this heavy burden they have to bear, and the thought of where their loved one is lying is unbearable. Could not an attempt be hastened to try and get those bodies in their proper resting place, by doing this you will give the only consolation there is to be given to those who are left behind suffering.

Letter from Margaret Capper to Sir Henry Walker, 12 November 1934. Catalogue reference: POWE 8/884

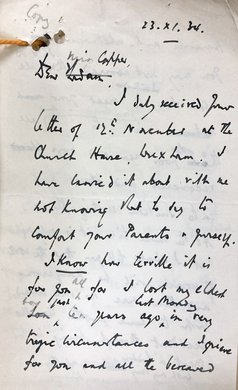

Later that month, on 23 November, Walker responded that he'd been carrying her letter with him 'not knowing what to try to comfort your parents and yourself'. He had himself lost a son 'in very tragic circumstances’ and said he grieved for Margaret and 'all the bereaved parents and relatives.'

But he also pointed out that attempts to recover bodies would expose others to danger. He urged patience so as to avoid another accident and the pit remained closed.

Partial transcript

I duly received your letter of 12 November at the Church House, Wrexham. I have carried it about with me not knowing what to try to comfort your parents and yourself.

I know how terrible it is for you all for I lost my eldest boy just ten years ago last Monday in very tragic circumstances and I grieve for you and all the bereaved parents and relatives.

You may rest assured that I will do all I can to meet your wish to have your loved one and all the other poor men and boys recovered and put into a suitable resting place. At the same time it is only right that I should tell you that the work of recovery will be dangerous and I am sure no one would wish to have another terrible accident through being in too great a hurry.

I duly received your letter of 12 November at the Church House, Wrexham. I have carried it about with me not knowing what to try to comfort your parents and yourself.

I know how terrible it is for you all for I lost my eldest boy just ten years ago last Monday in very tragic circumstances and I grieve for you and all the bereaved parents and relatives.

You may rest assured that I will do all I can to meet your wish to have your loved one and all the other poor men and boys recovered and put into a suitable resting place. At the same time it is only right that I should tell you that the work of recovery will be dangerous and I am sure no one would wish to have another terrible accident through being in too great a hurry.

Letter from Sir Henry Walker to Margaret Capper, 23 November 1934. Catalogue reference: POWE 8/884

In March 1935, a recovery team was allowed to enter certain areas of the mine. While wearing breathing apparatus, the team built 'stoppings' for ventilation to bring fresh air into the pit. They were able to recover the body of John Lewis, the third man killed in the initial rescue attempt.

After two months, the recovery team had reached the Dennis section, but due to safety concerns were prevented from continuing far enough to retrieve the 254 bodies that remained underground.

Coal trucks and rails upended by the explosion at Gresford. One of the trucks has a message 'Same way back P Davis 11/3/35' written by Parry Davies from the recovery team. Catalogue reference: COAL 80/468

Writing to the Minister of Mines

By May, with still no progress made to recover the bodies, William Capper appealed to Ernest Brown, Minister of Mines. In response, Brown arranged for Sir Henry Walker to visit the Cappers' family home in Pentre Broughton.

I talked to them as kindly as I could but I had to tell them that it would not be honest to let them think there was any but the very slightest chance of the bodies being recovered…. I am afraid nothing will console the Mother for the loss of her son (she has another) who was 35 years of age, although she said she would be content if she could only have a piece of one of his bones.

Sir Henry Walker

On 4 June, one of the six survivors, Robert (Ted) Andrews, also wrote to Brown expressing frustration. He was concerned that the mine owners might reopen Gresford despite the victims remaining underground.

I am writing to you because I think you are the ruling body and can see that things are done right so we are asking you as men of power to stop coal coming up that pit if is to be their grave so we all can go there and erect a stone or something else so that we will know and everybody else will that is their grave. I know of one lady who has lost her husband there and has gone insane and another one if she hears the worst that they will never get her son she will go the same or it will kill her for it is as fresh today as it was the night it happened.

Robert (Ted) Andrews

After nine months of waiting, the bereaved relatives had been worn down. Trust in the authorities to recover the bodies was wearing thin.

Petitions

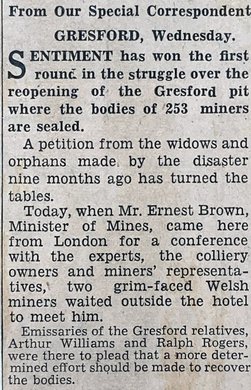

On 5 June 1935, Ralph Rogers, from Rhostyllen, wrote to Brown enclosing a petition signed by 319 people. It pleaded 'every possible effort should be made to recover the bodies before proceeding to produce coal at the above colliery.'

Rogers worked at Gresford along with his stepson, Walter Hughes (24), who been killed in the explosion. The Manchester Guardian reported a 'grim-faced' pair, including Rogers, waited outside a local hotel to personally deliver the petition to Ernest Brown.

Transcript

From Our Special Correspondent

Gresford, Wednesday.

Sentiment has won the first round in the struggle over the reopening of the Gresford pit where the bodies of 253 miners are sealed.

A petition from the widows and orphans made by the disaster nine months ago has turned the tables.

Today, when Mr Ernest Brown, Minister of Mines, came here from London for a conference with the experts, the colliery owners and miners’ representatives, two grim-faced Welsh miners waited outside the hotel to meet him.

Emissaries of the Gresford relatives, Arthur Williams and Ralph Rogers, were there to plead that a more determined effort should be made to recover the bodies.

From Our Special Correspondent

Gresford, Wednesday.

Sentiment has won the first round in the struggle over the reopening of the Gresford pit where the bodies of 253 miners are sealed.

A petition from the widows and orphans made by the disaster nine months ago has turned the tables.

Today, when Mr Ernest Brown, Minister of Mines, came here from London for a conference with the experts, the colliery owners and miners’ representatives, two grim-faced Welsh miners waited outside the hotel to meet him.

Emissaries of the Gresford relatives, Arthur Williams and Ralph Rogers, were there to plead that a more determined effort should be made to recover the bodies.

Report from the News Chronicle, 6 June 1935. Catalogue reference: POWE 8/884

As time went on, the community became concerned that the mine owners' need for profit would outweigh their need to respect the mine as the final resting place for 254 men and boys.

On 24 June 1935, Emily's daughter Edith wrote to Brown under her married name of Mrs M Lloyd. Expressing desperation, she outlined the widely held belief within the community that the authorities didn't want to recover the bodies or inspect the scene of the disaster in case it provided evidence of their culpability.

We have been very patient, waiting quietly, for nine long months in the hope that the rescue teams were working for that purpose [to recover the bodies] All the time they were preparing to get coal which apparently is all that matters even after murdering our men. If nothing is done to get them we can believe nothing else only that the officials want to hide their guilty secret of how they blew up the Gresford pit and murdered our brothers and fathers.

Mrs M Lloyd

The next day, Emily and William sent Brown their own petition, once again asking that efforts to recover the bodies of their loved ones continued.

In January 1936, against the pleas of the families to recover the bodies or close the mine, Gresford Colliery reopened for business. This was despite the ongoing inquiry, which wouldn't publish its findings until January 1937.

Gresford relief fund

Not only had the community lost loved ones, but they had also lost precious wages to support wives, children and parents. The miners tended to be paid on a Friday and many victims had collected their pay before going down the pit, which was now lost. On wages owed for the night, the mine owners decided to only pay up to the time of the explosion. With the mine closed until 1936, over 1,000 Gresford miners signed on the unemployment register.

However, public sympathy for the bereaved families was strong. Donations flooded into relief funds, which raised over £580,000. But disagreements around its management arose leading to suggestions the community was being treated unfairly.

The bereaved families of the Gresford victims will have been interested to hear that the money collected for them is considered to be too much. The committee is “embarrassed” and cannot, of course, hand it all over to... men and women of the lower classes.

The Daily Express, 16 January 1935

Five months later, a list of those in need of relief fund support was drawn up. William and Emily received 25 shillings a week.

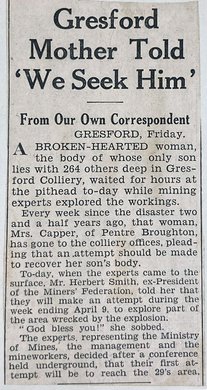

Emily is mentioned in a report on the administration of the relief fund, '[Emily] attends at the colliery office once a week to find out whether her son's body has been recovered. This is followed with equal regularity, by a visit to the County Court Registry to ask that an allowance for a tombstone be made "as soon as the body is found."'

The Cappers' story was covered in the Daily Herald, who reported 'A broken-hearted woman... waited for hours at the pithead to-day while mining experts explored the workings'.

Transcript

Gresford Mother Told ‘We Seek Him’

From Our Own Correspondent

Gresford, Friday.

A broken-hearted woman, the body of whose only son lies with 264 others deep in Gresford Colliery, waited for hours at the pithead to-day while mining experts explored the workings.

Every week since the disaster two and a half years ago, that woman, Mrs. Capper, of Pentre Broughton, has gone to the colliery offices, pleading that an attempt should be made to recover her son’s body.

To-day, when the experts came to the surface, Mr Herbert Smith, ex-President of the Miners’ Federation, told her that they will make an attempt during the week ending April 9, to explore part of the area wrecked by the explosion.

“God bless you!” she sobbed.

The experts, representing the Ministry of Mines, the management and the mineworkers, decided after a conference held underground, that their first attempt will be to reach the 29’s area.

Gresford Mother Told ‘We Seek Him’

From Our Own Correspondent

Gresford, Friday.

A broken-hearted woman, the body of whose only son lies with 264 others deep in Gresford Colliery, waited for hours at the pithead to-day while mining experts explored the workings.

Every week since the disaster two and a half years ago, that woman, Mrs. Capper, of Pentre Broughton, has gone to the colliery offices, pleading that an attempt should be made to recover her son’s body.

To-day, when the experts came to the surface, Mr Herbert Smith, ex-President of the Miners’ Federation, told her that they will make an attempt during the week ending April 9, to explore part of the area wrecked by the explosion.

“God bless you!” she sobbed.

The experts, representing the Ministry of Mines, the management and the mineworkers, decided after a conference held underground, that their first attempt will be to reach the 29’s area.

Report from the Daily Herald, 20 March 1937. Catalogue reference: POWE 8/914

The inquiry

Sir Henry Walker's inquiry into the disaster was published in January 1937, but it failed to attribute any outright blame or definitive cause of the explosion that took place in the early hours of 22 September 1934. Its conclusions were contentious, with the Gresford community feeling they had been given false promises. They viewed the Mines Inspectorate and mine owners as being on the same side, with the interests of the miners and their families being considered secondary.

Still pursuing justice for her son, in July 1937, Emily wrote to the MP for Wrexham, Robert Richards, enclosing a petition with 2,158 names, filling three notebooks.

Her accompanying letter expressed a sense of injustice and bitterness. After patiently waiting and trusting that the authorities would do all they could to retrieve the bodies, she believed the needs of the working community were being disregarded in favour of greed and profit.

We all feel that we are disgracefully treated and had this disaster happened in any other part of the country except north Wales, the bodies would have been brought to the surface before now… We have lost all faith in anything they tell us now… It is no use of us making any enquiries at Gresford now they are too busy getting coal. It is of no consequence to them that they have killed our men and are keeping them down there… The greed for coal in Gresford is as bad as before the disaster. We say it is a disgrace to humanity and we are beginning to wonder if we live in a civilised country.

Emily Capper

Coroner's inquest

In December 1934, the East Denbighshire coroner opened an inquest into the deaths of the seven miners and three rescue men whose bodies had been recovered. But, after ascertaining their identities, he delayed the inquest 'pending the Government Inquiry into the cause of the Disaster'.

With the inquest pending, it wasn't possible for the deaths of any of the victims to be officially registered. It wasn't until June 1938 that the Secretary of State, Sir Samuel Hoare, issued a request for the inquest to resume.

Finally, in October 1938, four years after the disaster, the inquest returned verdicts of 'death from carbon monoxide poisoning as the result of an explosion' for the 10 men whose bodies had been recovered. The same verdict was reached on 57 of those whose bodies had not been recovered, but then the inquest was adjourned again until 9 November.

Once resumed, the coroner concluded that the remaining deaths were the result of the explosion, but that there was not sufficient evidence to show how the explosion occurred. Following this, it was decided to close the inquest.

Transcript

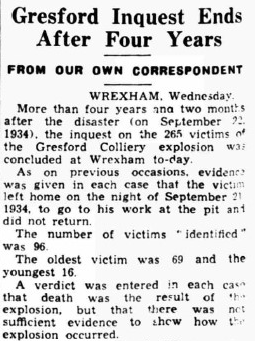

Gresford Inquest Ends After Four Years

FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT

WREXHAM. Wednesday.

More than four years and two months after the disaster (on September 23 1934) the inquest on the 265 victims of the Gresford Colliery explosion was concluded at Wrexham to-day.

As on previous occasions, evidence was given in each case that the victim left home on the night of September 21 1934, to go to his work at the pit and did not return.

The number of victims "identified" was 96.

The oldest victim was 69 and the youngest 16.

A verdict was entered in each case that death was the result of the explosion, but that there was not sufficient evidence to show how the explosion occurred.

Gresford Inquest Ends After Four Years

FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT

WREXHAM. Wednesday.

More than four years and two months after the disaster (on September 23 1934) the inquest on the 265 victims of the Gresford Colliery explosion was concluded at Wrexham to-day.

As on previous occasions, evidence was given in each case that the victim left home on the night of September 21 1934, to go to his work at the pit and did not return.

The number of victims "identified" was 96.

The oldest victim was 69 and the youngest 16.

A verdict was entered in each case that death was the result of the explosion, but that there was not sufficient evidence to show how the explosion occurred.

Report from the Western Mail on the Coroner's verdict for the victims of the Gresford Disaster, 1 December 1938. British Newspaper Archive (BNA)

Emily saw this as removing the last hope she had that the bodies might be recovered. She wrote to Sir Samuel Hoare, Secretary of State, on 21 November 1938, pleading 'As the mother of one of the men lost in the Gresford Disaster I beg of you not to close the Inquests until some attempt has been made to get the bodies'.

He replied that while he felt deepest sympathy with Emily and the other families, he did not have any authority in the matter and was unable to help.

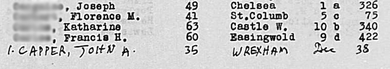

The index to deaths registered in July to September 1934 shows a handwritten addition with the name 'Capper, John A.' and the date December 1938, indicating that once the inquest closed the deaths of the victims were finally registered.

John Capper's entry on the death register in July to September 1934. England and Wales deaths 1837-2007, Denbighshire, Page Dec'38, courtesy of FindMyPast

Years following the disaster

William died in 1949 aged 78, and Emily in 1962 at 88.

Gresford Colliery closed in 1973 and Margaret campaigned for a permanent memorial along with miners' agent Ted McKay.

In 1982 this was achieved. A wheel from the pit head winding gear, once used to transport miners in and out of the pit, was erected close to the site of the Gresford pit. The memorial was unveiled by the then Prince and Princess of Wales.

The Gresford Disaster Memorial unveiling, 26 November 1982. Catalogue reference: COAL 80/468

The memorial commemorates the 266 lives lost: 261 miners killed in the explosion, the three men from the rescue team, George Brown (the man killed by flying debris on the surface) and 22-year-old Frederick Strange, who died in hospital on 14 October 1934. It was reported in The Leader that Frederick's death 'was hastened by the shock when he received the news of this brother' who had been killed in the disaster. Of the 266 victims, 254 were never recovered.

In 1987, Margaret, still living in the family home in Wrexham Road, wrote to Ted Mckay:

I am very proud and thankful for what we have achieved together. It was a God send when you came along to help me with what I was trying to do for 48 years. I could see your mind was the same as mine, those men were worthy of remembrance.

Margaret Capper

Margaret Capper herself passed away in 1992 aged 90.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Correspondence and petitions regarding the recovery of bodies at Gresford

- Date

- 12 November 1934 – 28 July 1937

-

- Title

- Photographs of Gresford Colliery

- Date

- 1905 – 1982

-

- Title

- Exploration of sealed areas at Gresford

- Date

- 1937

-

- Title

- The victims of the Gresford Colliery disaster

- Date

- September 1934 – April 1936