Early life

Elvira Chaudoir was born in 1911, though her British Secret Service file KV 2/2098, held at The National Archives, does not reveal where. The daughter of a wealthy Peruvian diplomat, she was raised in Paris, and could speak English, French and Spanish fluently.

At 23, Elvira married a Belgian banker, Jean Chaudoir, but soon began to find life ‘in Brussels exceedingly dull’ since she ‘had nothing in common’ with him. Elvira made off for Cannes where she spent much of her time gambling and socialising.

Upon the Nazis’ invasion of France in 1940, she left for the bars and casinos of London, where her life of espionage would begin.

Claude Dansey and MI6

Having racked up serious gambling debts, Elvira sought employment with the BBC in London. She took up translation work, but soon found this dreary – a fact she did not cover up. In April 1942, she was overheard complaining of her financial woes by an unassuming RAF officer. This officer, recognising Elvira's friends in ‘high circles’ and clear intelligence, recommended her to a Mr Claude Dansey – the assistant chief of MI6, the British Secret Intelligence Service.

The pair met at the Connaught Hotel, where Dansey offered Elvira employment as a British secret agent. The idea was to ‘coat-trail’– that is, she was to hover around French bars, in hope of running into a German spy who might seek to employ her, thus, becoming a double agent. Elvira’s diplomatic passport would ease travel, while her parents residing in Vichy France would make for a convenient excuse for her coming and going between France and Britain.

Transcript

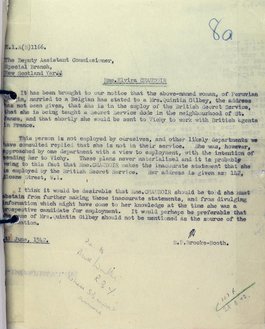

The Deputy Assistant Commissioner,

Special Branch,

New Scotland Yard

Name. Elvira CHAUDOIR

It has been brought to our notice that the above-named woman, of Peruvian origin, married to a Belgian has stated to a Mrs. Quintin Gilbey, the address has not been given, that she is in the employ of the British Secret Service, that she is being taught a Secret Service dode in the neighbourhood of St. James, and that shortly she would be sent to Vichy to work with British agents in France.

This person is not employed by ourselves, and other likely departments we have consulted replied that she is not in their service. She was, however, approached by one department with a view to employment, with the intention of sending her to Vichy. These plans never materialised and it is probably owing to this fact that Name. CHAUDOIR makes the inaccurate statement that she is employed by the British Secret Service...

I think it would be desirable that Name. CHAUDOIR should be told she must abstain from further making these inaccurate statements, and from divulging information which might have come to her knowledge at the time she was a prospective candidate for employment. It would perhaps be preferable that the name of Mrs. Quintin Gilbey should not be mentioned as the source of the information.

June, 1942,

S.P.Brocke-Booth

The Deputy Assistant Commissioner,

Special Branch,

New Scotland Yard

Name. Elvira CHAUDOIR

It has been brought to our notice that the above-named woman, of Peruvian origin, married to a Belgian has stated to a Mrs. Quintin Gilbey, the address has not been given, that she is in the employ of the British Secret Service, that she is being taught a Secret Service dode in the neighbourhood of St. James, and that shortly she would be sent to Vichy to work with British agents in France.

This person is not employed by ourselves, and other likely departments we have consulted replied that she is not in their service. She was, however, approached by one department with a view to employment, with the intention of sending her to Vichy. These plans never materialised and it is probably owing to this fact that Name. CHAUDOIR makes the inaccurate statement that she is employed by the British Secret Service...

I think it would be desirable that Name. CHAUDOIR should be told she must abstain from further making these inaccurate statements, and from divulging information which might have come to her knowledge at the time she was a prospective candidate for employment. It would perhaps be preferable that the name of Mrs. Quintin Gilbey should not be mentioned as the source of the information.

June, 1942,

S.P.Brocke-Booth

Soon after being employed by British Secret Services, Elvira was given a stern telling off for bragging of her espionage to friends. Catalogue reference: KV 2/2098.

Coat-trailing in France

Most of the information we hold on Elvira is in the words of others, namely of the men she worked for. However, there are glimpses of Elvira in her own words.

Contained within the file KV 2/2098, we find a compelling narrative detailing Elvira's coat-trailing adventure in Cannes, August 1942. Here, she runs into an old friend, Henri Chauvel, a prisoner of war turned collaborationist. He refers to a German friend that Elvira must meet. She takes up the offer, gladly.

With the suggestion of flirtation, the mysterious German takes Elvira ‘to the most expensive black-market restaurant’. She describes him affectionately, with ‘very good manners’ and ‘enjoying everything like a child’, even if he did have a bit of a drink problem. She notices, with sympathy, the man’s fear of ‘look(ing) German’ in Unoccupied France (for danger of being identified by the Resistance) and how he was ‘quite pleased’ when she said he did not. Having got to know one another, the man reveals his name – ‘Bibi’. In reality, the man was Helmut Bliel – a semi-official German intelligence (Abwehr) agent personally appointed by Herman Goering, Adolf Hitler’s second-in-command. Nonetheless, this did not seem to threaten Elvira.

The couple proceed to spend three nights together, frequenting casinos and the beaches of Eden-Roc, Cannes. Here Bliel pronounces he must see her again, if not for ‘wonderful parties’ then to ‘do some little business together’. Elvira’s ears prick up. On the deserted waterfront, they talk until three in the morning. He expresses he had ‘acted on intuition’ and ‘just felt’ he could trust her, and that, if she failed him, it would ‘ruin his whole career’. With a pang of guilt, Elvira swears her secrecy to him – she ‘will never tell a soul’ of their conversation.

I felt rather sorry for him and frankly almost wished I had kept out of all this, but bucked myself up thinking that once you start doing a job you must do it fully and shut all softness away.

Elvira Chaudoir

The arrangement is agreed. For £100 per month, she will send economic information to Bliel. She refuses to reveal anything that could harm the British. Having sealed the deal, they retreat to Bliel’s hotel room for a lesson in her most vital skill – letter writing with secret ink.

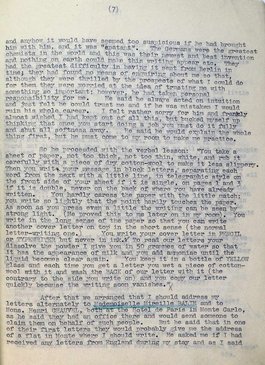

Partial transcript

The Germans were the greatest chemists in the world and this was their newest and best invention and nothing on earth could make this writing appear etc. They had the greatest difficulty in having it sent from Berlin in time; they had found no means of enquiring about me so that, although they were thrilled by the prospects of what I could do for them they were worried at the idea of trusting me with something so important; however, he had taken personal responsibility for me. He said he always acted on intuition and just felt he could trust me and if he was mistaken I would ruin his whole career. I felt rather sorry for him and frankly almost wished I had kept out of all this, but bucked myself up thinking that once you start doing a job you must do it fully and shut all softness away. He said he would explain the whole thing first, but he must come to my room to make me practice.

So he proceeded with the verbal lesson: "You take a sheet of paper, not too thick, not too thin, white, and rub it carefully with a piece of dry cotton-wool to make it less slippery. Then you write your message in block letters, separating each word from the next with a little line, in the telegraphic style on the front side of your sheet if it is single, on pages 1 and 3 if it is double, never on the back of where you have already written. You hardly caress the paper with the little match; you write so lightly that the point hardly touches the paper...'

The Germans were the greatest chemists in the world and this was their newest and best invention and nothing on earth could make this writing appear etc. They had the greatest difficulty in having it sent from Berlin in time; they had found no means of enquiring about me so that, although they were thrilled by the prospects of what I could do for them they were worried at the idea of trusting me with something so important; however, he had taken personal responsibility for me. He said he always acted on intuition and just felt he could trust me and if he was mistaken I would ruin his whole career. I felt rather sorry for him and frankly almost wished I had kept out of all this, but bucked myself up thinking that once you start doing a job you must do it fully and shut all softness away. He said he would explain the whole thing first, but he must come to my room to make me practice.

So he proceeded with the verbal lesson: "You take a sheet of paper, not too thick, not too thin, white, and rub it carefully with a piece of dry cotton-wool to make it less slippery. Then you write your message in block letters, separating each word from the next with a little line, in the telegraphic style on the front side of your sheet if it is single, on pages 1 and 3 if it is double, never on the back of where you have already written. You hardly caress the paper with the little match; you write so lightly that the point hardly touches the paper...'

In an interview with MI5, Elvira shares details of her lesson in secret letter writing. Catalogue reference: KV 2/2098.

The Twenty Committee

Upon her return, Elvira shared her information in an interview with a panel of MI5 agents. Though its Chairman, Sir John Cecil Masterman, was reluctant to allow it, on 28 October 1942 she was formally invited to join the Twenty Committee – a play on the Roman numerals ‘XX’ (i.e. a double cross). She would be known as Agent Bronx, after the wartime cocktail she ordered upon meeting them.

At first, Bronx sent basic information to the Germans – some true, some false – detailing Britain’s industrial and economic affairs. On one occasion, she is credited with preventing a chemical attack on London by alleging the British had a chemical store themselves ready to be used in retaliation.

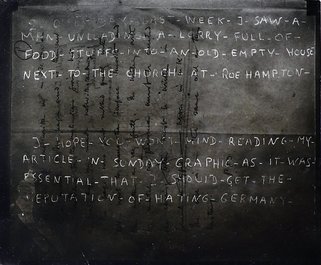

Alongside this, she wrote fiercely anti-German propaganda in newspapers such as The Sunday Graphic, for which she apologises to Bliel in a coded letter.

I hope you won't mind reading my article in Sunday Graphic as it was essential that I should get the reputation of hating Germany.

Elvira Chaudoir

Partial transcript

I hope you won't mind reading my article in Sunday Graphic as it was essential that I should get the reputation of hating Germany.

I hope you won't mind reading my article in Sunday Graphic as it was essential that I should get the reputation of hating Germany.

Elvira's coded letter with an apology to Bliel. Catalogue reference: KV 2/2098

Her file reveals that the MI5 believed the Germans trusted her immensely. In deciphered Most Secret Sources, she is referred to as a ‘reliable agent’ in which they have ‘full confidence’. It is this detail that made her an ideal candidate for her most important mission yet – Plan Ironside.

Plan Ironside

In 1944, as D-Day approached, a related lesser-known operation was in the works, Plan Ironside – a plan to deceive the German army into expecting an attack in the wrong part of France. Bronx would be key to this.

Bronx’s usual form of communication was to send letters by post to Cannes, but wartime post was notoriously slow. In the case of an imminent attack, Bronx was to send a telegram to a bank based in Lisbon. Using a simple code, she wrote: ‘Urgently need £50 to pay my dentist’. This translated to: ‘I am certain an attack will take place in the Bay of Biscay within two weeks’. This was sent on 27 May 1944, 10 days before the planned invasion of Normandy on 5 June.

Partial transcript

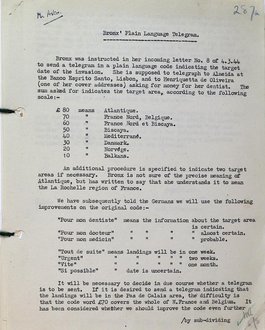

Bronx' Plain Language Telegram

Bronx was instructed in her incoming letter No. 8 of 4.3.44 to send a telegram in a plain language code indicating the target date of the invasion. She is supposed to telegraph to Almeida at the Banco Esprito Santo, Lisbon, and to Henriquetta de Oliveira (one of her cover addresses) asking for money for her dentist. The sum asked for indicated the target area, according to the following scale:–

£80 means Atlantique.

£70 means France Nord, Belgique.

£60 means France Nord et Biscaya.

£50 means Miditerrane.

£30 means Danmark.

£20 means Norvege.

£10 means Balkans.

And additional procedure is specified to indicate two target areas if necessary. Bronx is not sure of the precise meaning of Atlantique, but has written to say that she understands it to mean the La Rochelle region of France.

We have subsequently told the Germans we will use the following improvements on the original code:–

"Pour mon dentiste" means the information about the target area is certain.

"Pour mon docteur" means the information about the target area is almost certain.

"Pour mon medicin means the information about the target area is probable.

"Tout de suite" means landings will be in one week.

"Urgent" means landings will be in two weeks.

"Vite" means landing will be in one month.

"Si possible" means date is uncertain.

It will be necessary to decide in due course whether a telegram is to be sent...

Bronx' Plain Language Telegram

Bronx was instructed in her incoming letter No. 8 of 4.3.44 to send a telegram in a plain language code indicating the target date of the invasion. She is supposed to telegraph to Almeida at the Banco Esprito Santo, Lisbon, and to Henriquetta de Oliveira (one of her cover addresses) asking for money for her dentist. The sum asked for indicated the target area, according to the following scale:–

£80 means Atlantique.

£70 means France Nord, Belgique.

£60 means France Nord et Biscaya.

£50 means Miditerrane.

£30 means Danmark.

£20 means Norvege.

£10 means Balkans.

And additional procedure is specified to indicate two target areas if necessary. Bronx is not sure of the precise meaning of Atlantique, but has written to say that she understands it to mean the La Rochelle region of France.

We have subsequently told the Germans we will use the following improvements on the original code:–

"Pour mon dentiste" means the information about the target area is certain.

"Pour mon docteur" means the information about the target area is almost certain.

"Pour mon medicin means the information about the target area is probable.

"Tout de suite" means landings will be in one week.

"Urgent" means landings will be in two weeks.

"Vite" means landing will be in one month.

"Si possible" means date is uncertain.

It will be necessary to decide in due course whether a telegram is to be sent...

Details of the code used by Bronx in Plan Ironside. Catalogue reference: KV 2/2098.

In her craftiest move yet, Bronx sent the telegram accompanied by a letter. In it, she wrote she had received the information of the attack from a drunken British diplomat. She alleges the man was so embarrassed by his behaviour that he came to apologise to her the next morning. He stated the attack had since been postponed by a month and not to repeat this to anyone. Of course, the letter would not arrive for another two weeks – well after the entire 11th Panzer Division had been left in Bordeaux on the Bay of Biscay, awaiting an attack that would never come.

Spying on a spy

Despite her intelligence successes, it seems the British Security Service didn’t entirely trust Bronx. They tapped her telephone calls and monitored movements from her Mayfair flat, details of which are prevalent in her file.

This surveillance reveals interesting insights into Elvira's private life. Her handling officer, Christopher Harmer, notes with subtle distaste that she lives with a man that is not her husband. She hosts frequent parties, spends most nights playing poker, and, most interestingly, is noted as having ‘lesbian tendencies’. In other words, Elvira was a woman unabashed by the social norms of the time.

Further research into Elvira's ‘lesbian tendencies’ suggest she was in a romantic relationship with Monica Sheriffe, racehorse owner and family friend to the Windsors. In her first meeting with Bliel since Plan Ironside, Elvira told Harmer – if anything is to happen to me, tell Monica Sheriffe. Their relationship was deemed intimate enough that Harmer met Monica personally. He assured Masterman that he believed Elvira, ‘Miss Sheriffe knows nothing about her work’ with us.

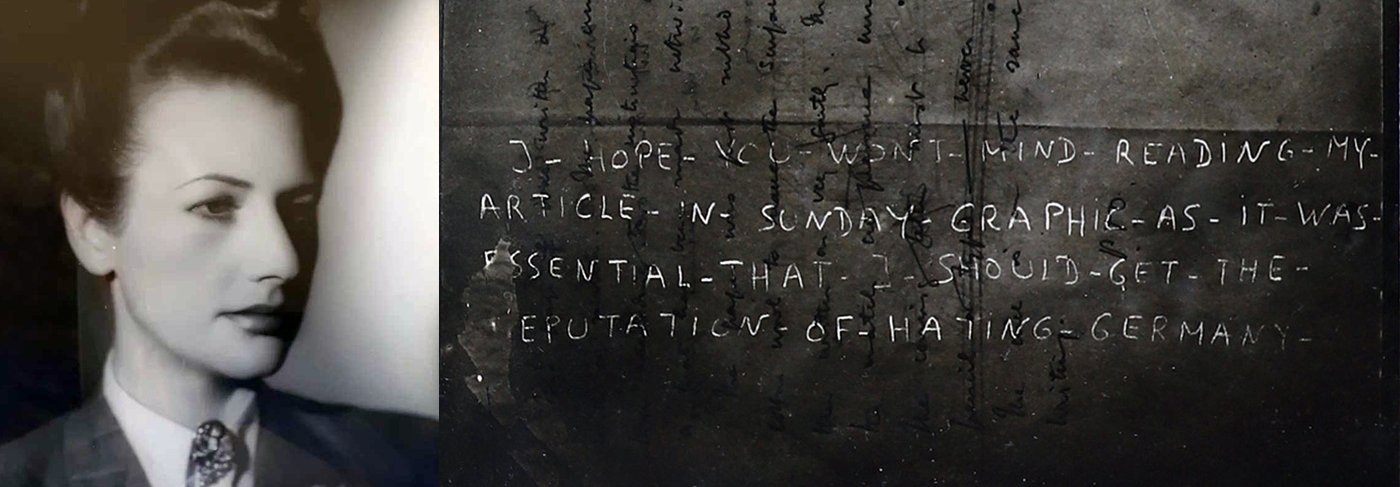

A photograph of Elvira Chaudoir, Agent Bronx, sent to Monica Sheriffe just before her she set off on her first coat-trailing mission in July, 1942. She writes: ‘to darling Monica, Elvira. July, 1942’. Provided by Goadby Marwood History Group.

Later life

After the war, Elvira, now in her mid-30s, left the world of intelligence and retired from espionage. Instead, she opted for a quieter life back in France on the French Riviera. Here, she opened a gift shop in the picturesque seaside town of Beaulieu-sur-Mer, where she spent the rest of her life.

Years later, in 1995, following an interview she gave discussing her life during the war, she received £5,000 from MI5 – a gift to remember her wartime services. She died in 1996 at the age of 85.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Elvira Chaudoir's British Secret Service file

- Date

- 1942–1945