Record revealed

A dramatic plea for Churchill’s help from Bletchley Park

In 1941, with Britain's future in peril, four Government Code and Cypher School cryptanalysts, including Alan Turing, made a stunning appeal directly to Winston Churchill. Bypassing management, their request broke all the rules, how would the Prime Minister respond?

Image 1 of 5

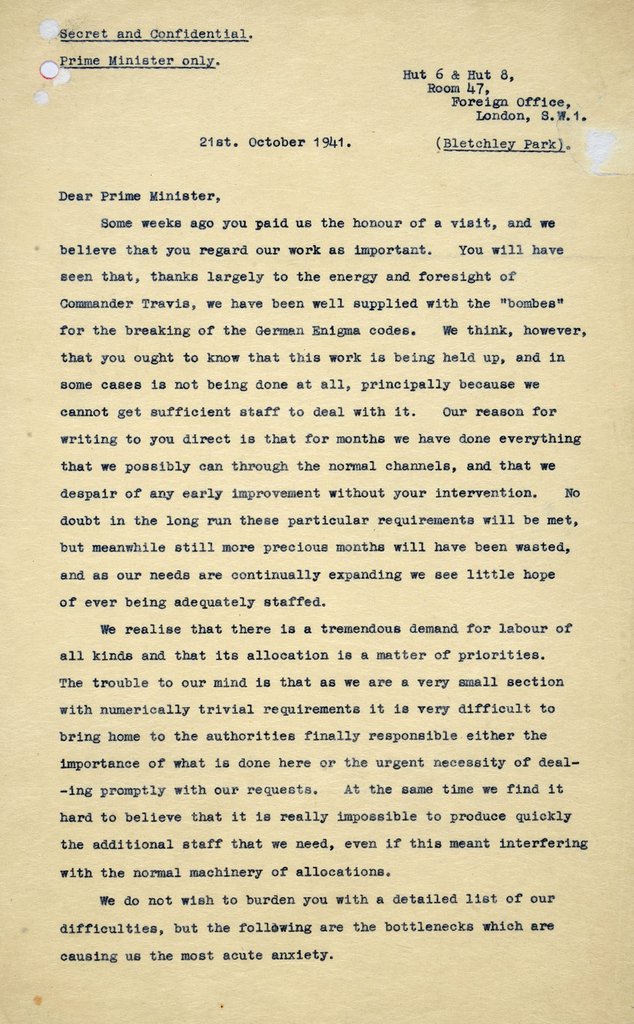

The letter sent to Winston Churchill requesting more resources to be allocated to Bletchley Park, 21 October 1941.

Partial transcript

21st. October 1941.

Dear Prime Minister,

Some weeks ago you paid us the honour of a visit, and we believe that you regard our work as important. You will have seen that, thanks largely to the energy and foresight of Commander Travis, we have been well supplied with the “bombes” for the breaking of the German Enigma codes. We think, however, that you ought to know that this work is being held up, and in some cases is not being done at all, principally because we cannot get sufficient staff to deal with it. Our reason for writing to you direct is that for months we have done everything that we possibly can through the normal channels, and that we despair of any early improvement without your intervention. No doubt in the long run these particular requirements will be met, but meanwhile still more precious months will have been wasted, and as our needs are continually expanding we see little hope of ever being adequately staffed.

We realise that there is a tremendous demand for labour of all kinds and that its allocation is a matter of priorities. The trouble to our mind is that as we are a very small section with numerically trivial requirements it is very difficult to bring home to the authorities finally responsible either the importance of what is done here or the urgent necessity of dealing promptly with our requests. At the same time we find it hard to believe that it is really impossible to produce quickly the additional staff that we need...

Image 2 of 5

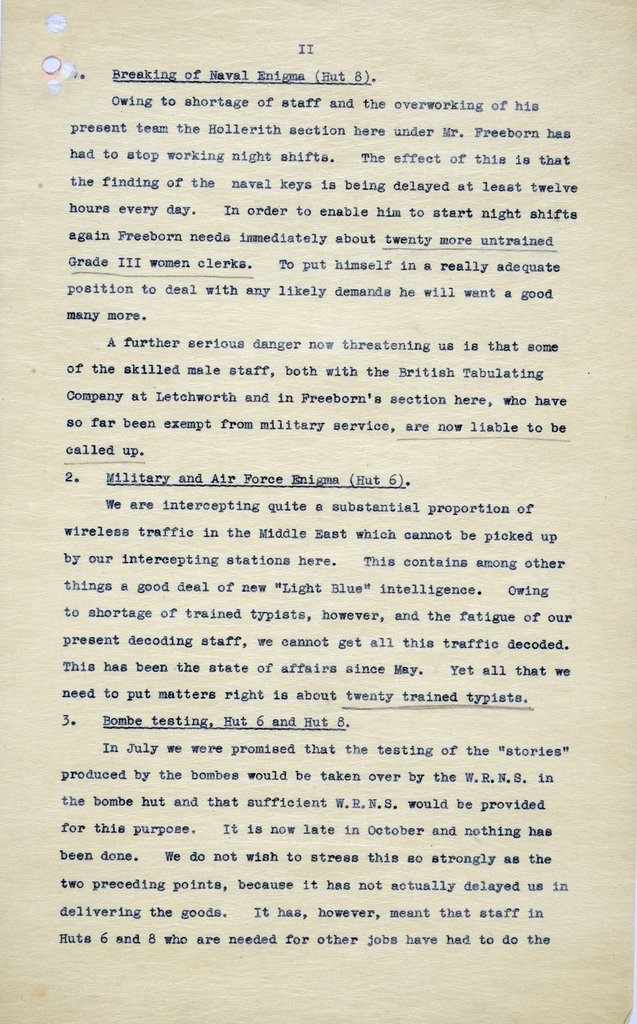

Page 2 of the letter sent to Winston Churchill.

Partial transcript

1. Breaking of Naval Enigma (Hut 8).

Owing to shortage of staff and the overworking of his present team the Hollerith section here under Mr. Freeborn has had to stop working night shifts. The effect of this is that the finding of the naval keys is being delayed at least twelve hours every day. In order to enable him to start night shifts again Freeborn needs immediately about twenty more untrained Grade III women clerks. To put himself in a really adequate position to deal with any likely demands he will want a good many more.

A further serious danger now threatening us is that some of the skilled male staff, both with the British Tabulating Company at Letchworth and in Freeborn’s section here, who have so far been exempt from military service, are now liable to be called up.

2. Military and Air Force Enigma (Hut 6).

We are intercepting quite a substantial proportion of wireless traffic in the Middle East which cannot be picked up by our intercepting stations here. This contains among other things a good deal of new “Light Blue” intelligence. Owing to shortage of trained typists, however, and the fatigue of our present decoding staff, we cannot get all this traffic decoded. This has been the state of affairs since May. Yet all that we need to put matters right is about twenty trained typists.

3. Bombe testing, Hut 6 and Hut 8.

In July we were promised that the testing of the “stories” produced by the bombes would be taken over by the W.R.N.S. in the bombe hut...

Image 3 of 5

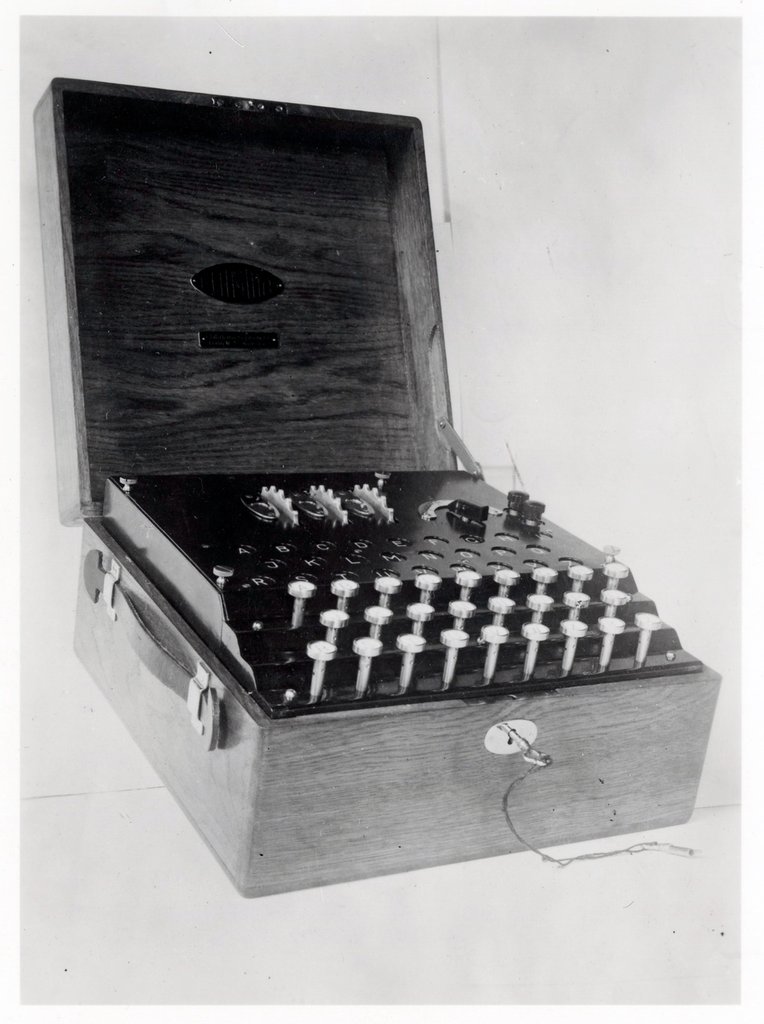

The Enigma machine, Germany’s chief method for enciphering their messages during the Second World War.

Image 4 of 5

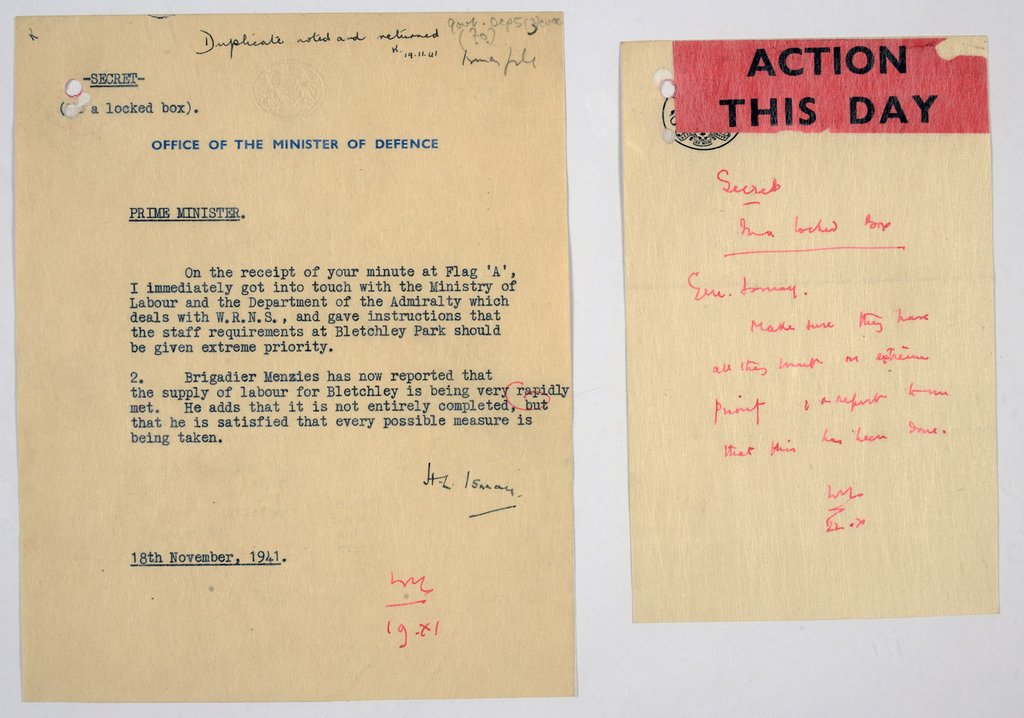

Churchill’s handwritten note dated 22 October 1941 to General Ismay, his chief military assistant, and, on the left, Ismay’s reply of 18 November.

Transcript

SECRET

OFFICE OF THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE

PRIME MINISTER.

On the receipt of your minute at Flag ‘A’, I immediately got into touch with the Ministry of Labour and the Department of the Admiralty which deals with W.R.N.S., and gave instructions that the staff requirements at Bletchley Park should be given extreme priority.

1. Brigadier Menzies has now reported that the supply of labour for Bletchley in being very rapidly met. He adds that it is not entirely completed, but that he is satisfied that every possible measure is being taken.

18th November, 1941.

[handwritten note]

Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done.

Image 5 of 5

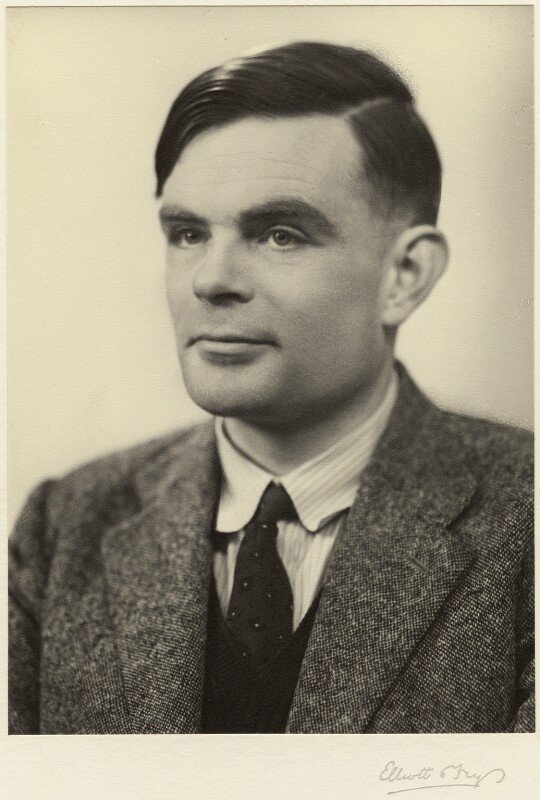

Photograph portrait of Alan Turing in 1951 by Elliott & Fry. ©National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Why this record matters

Date: 21 October 1941

At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the Enigma machine was Germany’s chief method for enciphering their messages, keeping them secret. To modern eyes it looks like an old-fashioned typewriter, but during the Second World War this was highly complex technology. It used rotating wheels and generated a massive number of combinations for enciphering.

Breaking the Enigma codes was a priority for the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), based at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire. As mentioned in the letter, the cryptanalysts (code breakers) were using 'bombes' (electro-mechanical devices) for the breaking of the Enigma codes. The organisation was divided into a series of huts in the grounds of Bletchley Park. The address on this letter refers to Hut 6 (dealing with Army and Air Force Enigma), and Hut 8 (Naval Enigma).

The Battle of the Atlantic was raging in 1941 and, by June, the cryptanalysts at Bletchley had broken into U-boat communications. But the battle for supremacy remained intense, and the team were encountering obstacles at their place of work. Under-resourcing was causing ‘bottlenecks’.

The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, had paid a visit to Bletchley Park in September 1941 to meet the front-line staff and to boost their morale. The cryptanalysts decided to capitalise on this by directly appealing to Churchill for help.

The authors Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman, Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry, made it clear that ‘we have written this letter entirely on our own initiative’. They were at pains to point out that no blame should be attributed to Commander Travis, who had responsibility for the Enigma decryption teams. When this initiative came to light it caused tensions at Bletchley Park and the signatories were dubbed the ‘wicked uncles’.

In the letter they asked for 20 more women clerks, and 20 trained typists, and a detachment of the WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service) to help test the 'bombes'.

Churchill emphatically backed the request. Immediately upon receiving the letter, he sent a handwritten note to General Ismay, his Chief military adviser, bearing a red ‘Action This Day’ sticker, giving a powerful sense of urgency and reflecting his dynamism. It reads: ‘Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done’. On 18 November Ismay reported back to Churchill that ‘Brigadier Menzies [the Chief of MI6] has now reported that the supply of labour for Bletchley is being very rapidly set. He adds that it is not entirely completed, but that he is satisfied that every possible measure is being taken’.

This letter demonstrates the sheer determination of Alan Turing and his co-signatories. Acutely aware of the high stakes involved, they were prepared to take a risk and break all the rules by going over the heads of the management of GC&CS by directly appealing to the Prime Minister for more resources. And Churchill’s response shows that he grasped the importance of the matter immediately. Turing and GC&CS's work would prove vital to the Allied victory.