The black man and his party

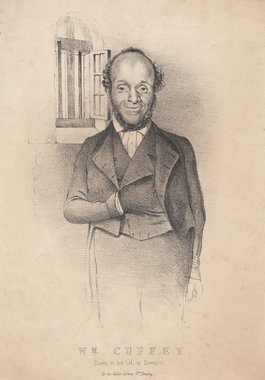

William Cuffey was born in 1788 in Chatham, Kent. His name has also been written Cuffay and Cuffy, but all are now thought to be anglicised versions of Kofi.

His father was enslaved in St Kitts but became a free man and ship’s cook. Today William Cuffey might have been considered disabled as he reportedly had a spinal deformity. He worked as a tailor in London, becoming politically active through a strike in 1834. By 1839 he was a Chartist, famed for his powerful oratory and leadership.

Chartism was a movement for the rights and suffrage of the working class based on the People’s Charter – a petition of six demands for reforms, the vote for all men over the age of 21 being the most significant. Cuffey became so prominent in the movement that in 1848 The Times referred to his section of chartists as ‘the black man and his party’.

Chartist Convention

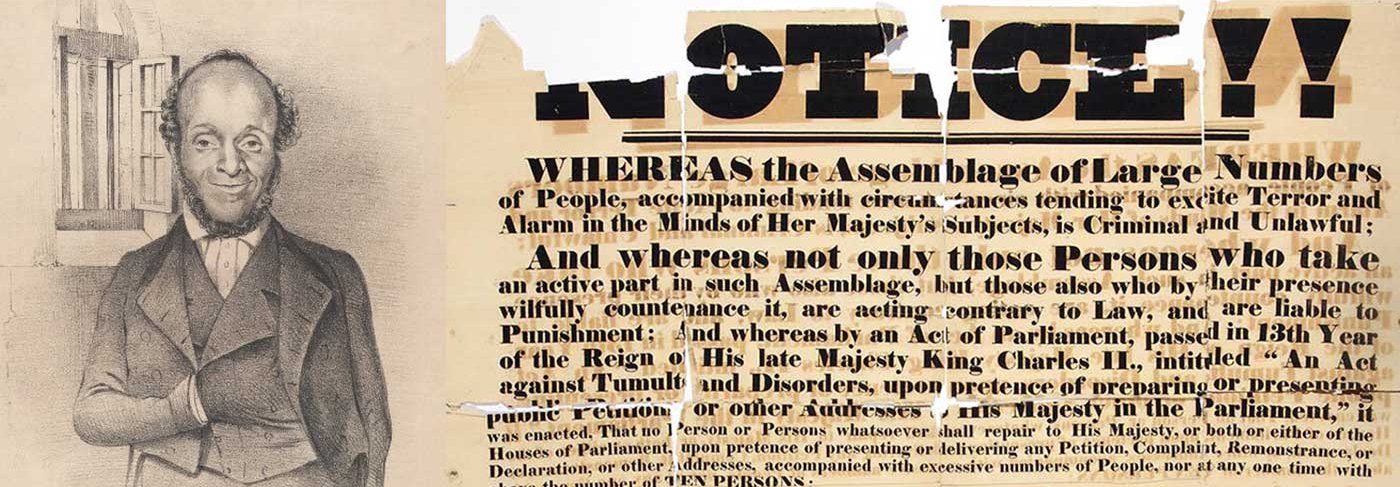

Cuffey was involved in the Chartist Convention which organised a demonstration on Kennington Common in April 1848. Around 25,000 people gathered to march to Parliament with a ‘monster petition’. The government were clearly nervous of its potential. In preparation, thousands of special constables were recruited, institutions such as the Royal Mint and the Foreign Office requested greater protection from the Home Office, and lamps were to be lit early.

Partial transcript

NOTICE!

WHEREAS the Assemblage of Large Numbers of People, accompanied with circumstances tending to excite Terror and Alarm in the Minds of Her Majesty’s Subjects, is Criminal and Unlawful

[…]

And whereas a MEETING has been called to assemble on MONDAY next, the 10th inst., at KENNINGTON COMMON, and it is announced in the Printed Notices calling such Meeting, that it is intended by certain Persons to repair thence in Procession to the House of Commons, accompanied with excessive numbers of People, upon pretence of presenting a Petition to the Commons House of Parliament; And whereas information has been received that Persons have been advised to procure Arms and Weapons, with the purpose of carrying the same in such Procession; And whereas such proposed Procession is calculated to excite Terror and alarm in the minds of Her Majesty’s Subjects;

ALL PERSONS ARE HEYBY CAUTIONED AND STRICTLY ENJOINED not to attend or take part in, or be present at any such Assemblage or Procession

[…]

C. Rowan

R. Mayne

Commissioners of the Police of the Metropolis

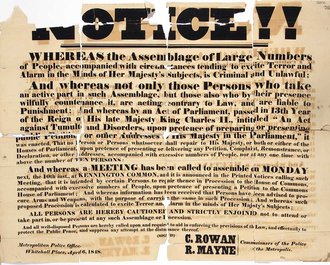

NOTICE!

WHEREAS the Assemblage of Large Numbers of People, accompanied with circumstances tending to excite Terror and Alarm in the Minds of Her Majesty’s Subjects, is Criminal and Unlawful

[…]

And whereas a MEETING has been called to assemble on MONDAY next, the 10th inst., at KENNINGTON COMMON, and it is announced in the Printed Notices calling such Meeting, that it is intended by certain Persons to repair thence in Procession to the House of Commons, accompanied with excessive numbers of People, upon pretence of presenting a Petition to the Commons House of Parliament; And whereas information has been received that Persons have been advised to procure Arms and Weapons, with the purpose of carrying the same in such Procession; And whereas such proposed Procession is calculated to excite Terror and alarm in the minds of Her Majesty’s Subjects;

ALL PERSONS ARE HEYBY CAUTIONED AND STRICTLY ENJOINED not to attend or take part in, or be present at any such Assemblage or Procession

[…]

C. Rowan

R. Mayne

Commissioners of the Police of the Metropolis

A police notice ahead of the Kennington Common protest. Catalogue reference: HO 45/2510.

On the day of the protest, official reports describing that ‘great numbers have assembled’ also acknowledged that there were ‘numerous flags and banners but not the slightest appearance of arms’.

A set of cowardly humbugs

The march passed off peacefully, but the police prevented it from crossing the Thames. The petition was taken to Parliament by Chartist leader and politician Feargus O’Connor, but was later rejected, supposedly on the basis of the repetition of signatures and forgeries. The demonstration was considered a failure and Cuffey reportedly called the Convention ‘a set of cowardly humbugs’, believing that O’Connor had known of the plan to prevent the march in advance.

A few months later, in August 1848, William Cuffey was arrested for conspiring to ‘levy war against the queen, in order by force and constraint to compel her to change her councils’ and conspiring ‘with intent to depose the queen from the style, honour, and dignity of the imperial crown’ (CRIM 10/28).

William Cuffey in his cell in 1848. He was drawn by fellow Chartist William Paul Dowling © National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

The trial

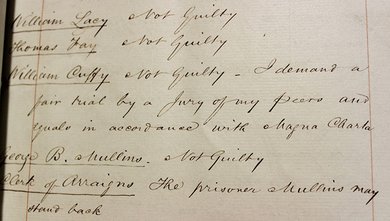

Cuffey was tried with two other Chartists, William Lacey and Thomas Fay. The National Archives holds the transcript of their trial.

A government spy called Powell alleged that Cuffey was planning an armed uprising. In court, Cuffey maintained his innocence, stating that the outcome of the trial was a foregone conclusion. While entering his plea, he also declared ‘I demand a fair trial by a jury of my peers and equals’. In this period, much like with voting, jurors had to meet a property qualification which barred much of the working class from taking part.

Partial transcript

William Cuffey: Not Guilty – I demand a fair trial by a Jury of my peers and equals in accordance with Magna Carta

William Cuffey: Not Guilty – I demand a fair trial by a Jury of my peers and equals in accordance with Magna Carta

William Cuffey’s plea. Catalogue reference: TS 36/43

Despite efforts to prove the evidence unreliable, the jury found the defendants guilty. In his speech to the judge, Cuffey stated that ‘The press has strongly excited the middle class against me, therefore I did not expect anything else except the verdict of guilty, right or wrong’. He went on to call the Attorney General ‘The Spy Master General’ and the government’s network of spies ‘a disgrace’.

In the face of a potential death sentence, Cuffey’s final words to the court were resolute:

I am not anxious for martyrdom but I feel that after what I have gone through this week I have the fortitude to endure any punishment your Lordship can inflict upon me. I know my cause is good and I have a self approving conscience that will bear me up against anything and that would bear me up even to the scaffold – therefore I think I can endure any punishment proudly. I feel no disgrace at being called a felon.

William Cuffey

-

- From our collection

- TS 36/43

- Title

- Full transcript of William Cuffey's trial

- Date

- 1848

-

- From our collection

- CRIM 10/28

- Title

- Abridged transcript of the trial

- Date

- 1848

Transported

In the end, Cuffey was sentenced to transportation for life. On 8 August 1849, aged 60, Cuffey set off aboard the Adelaide to the other side of the world: Van Diemen’s Land, or Tasmania as we call it today

-

- From our collection

- HO 11/16

- Title

- Record of William Cuffey's transportation to Australia

- Date

- 1849 – 1850

Although he was now old and in unfamiliar surroundings, this is not the end of Cuffey’s story. Despite receiving a pardon in 1856 Cuffey chose not to return to Britain and records in Australia show that he grew to be an important campaigner in his new home as well. Upon his death in 1870, at an impressive 82 years old, a number of obituaries were published. The Maitland Mercury said that ‘he always supported the people’s side, and opposed everything that tended to cripple the rights of the people.'

Back in Britain, the Reform Act of 1867 – which gave the vote to many working class men for the first time – was passed in Cuffey’s lifetime, but full male suffrage was only achieved in 1918.

A pioneer of his day, Cuffey was important to social movements and political reform on two opposite sides of the globe. He was a disabled, working-class leader, and the historical significance of his life should be recognised.

This article is based on a National Archives blog by Harriet Craig, originally published 19 October 2017.