Record revealed

The Treason Act

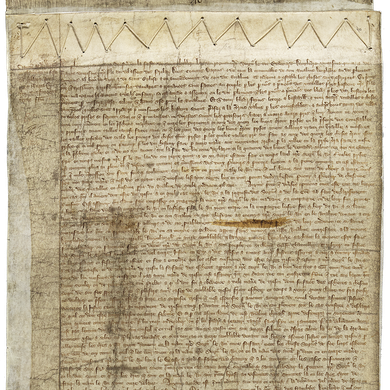

The Treason Act of 1352 – or ‘Great Statutes of Treason’ as it is sometimes known – defined the crime of ‘high treason’ in law for the first time. It is one of the oldest pieces of legislation still on the statute book today.

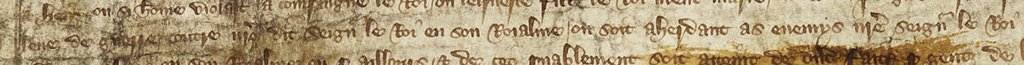

Image 1 of 4

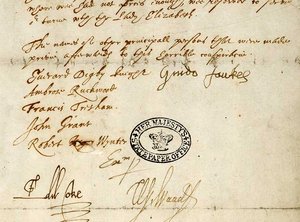

The Treason Act, written in medieval French.

Translation

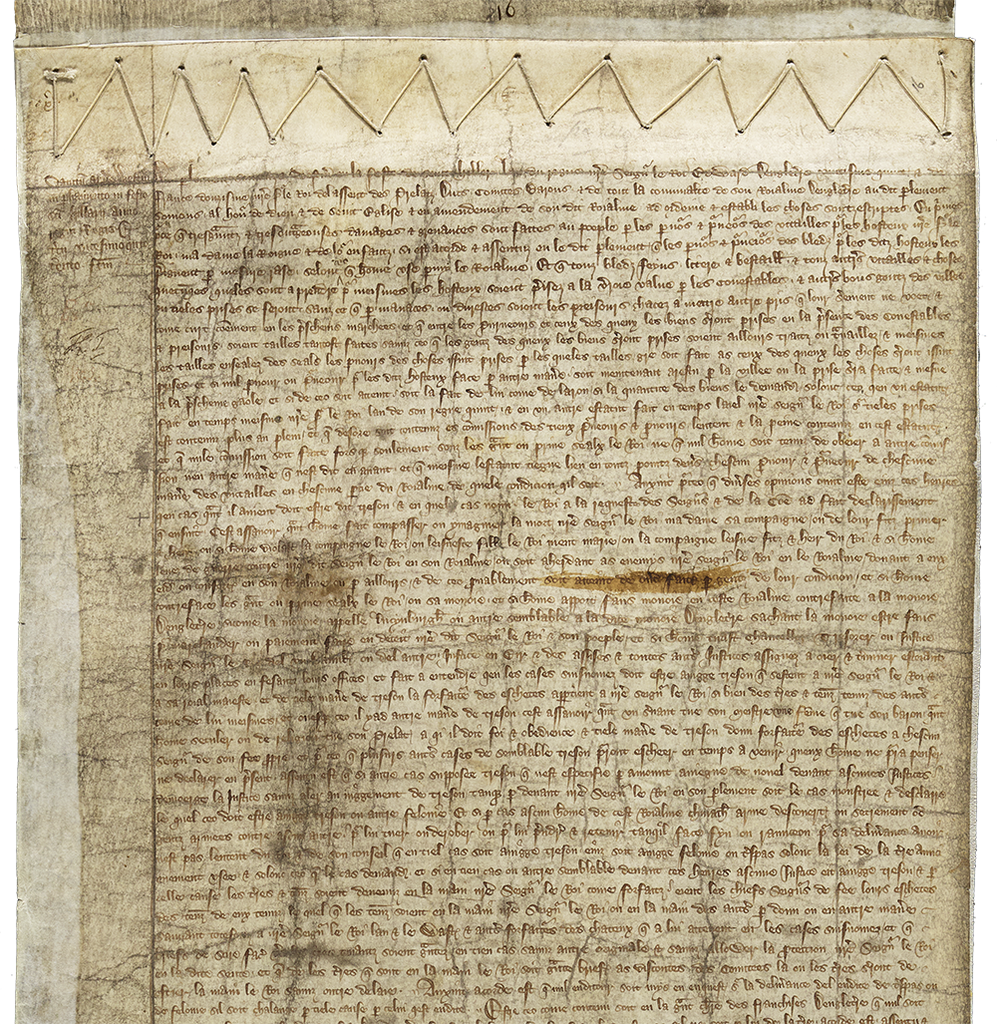

Whereas diverse opinions have been before this time in what case treason shall be said, and in what not; the King, at the request of the Lords and of the Commons, has made a declaration in the manner as hereafter follows, that is to say; when a man does compass or imagine the death of our Lord the King, or of our Lady his Queen or of their eldest son and heir; or if a man do violate the King’s companion, or the King’s eldest daughter unmarried, or the wife of the King’s eldest son and heir; or if a man do levy war against our Lord the King in his realm, or be adherent to the King’s enemies in his realm, giving to them aid and comfort in the realm, or elsewhere, and thereof be probably attainted of open deed by the people of their condition: and if a man counterfeit the King’s Great or Privy Seal, or his money; and if a man bring false money into this realm, counterfeit to the money of England, as the money called Lushburgh, or other, like to the said money of England, knowing the money to be false, to merchandise or make payment in deceit of our said Lord the King and of his people; and if a man slay the Chancellor, Treasurer, or the King’s Justices of the one Bench or the other, Justices in Eyre, or Justices of Assise, and all other Justices assigned to hear and determine, being in their places, doing their offices: and it is to be understood, that in the cases above rehearsed, that ought to be judged treason which extends to our Lord the King, and his Royal Majesty.

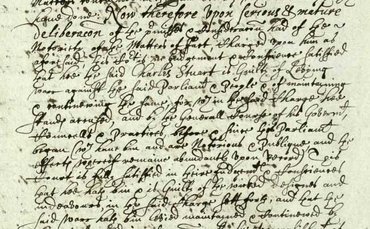

Image 2 of 4

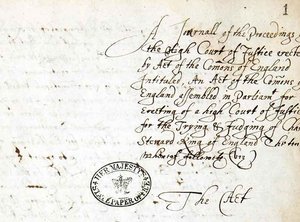

This section of the act defines ‘high treason’, made up of five central clauses.

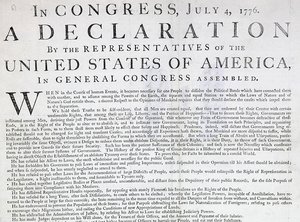

Image 3 of 4

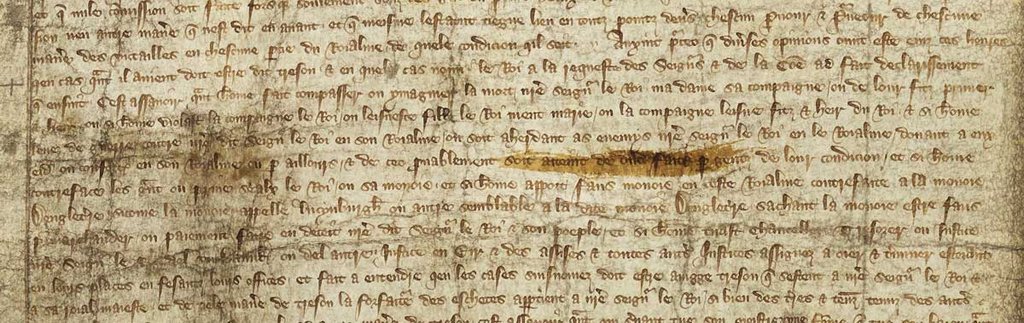

The main treasonous crime defined was ‘compassing or imagining the death of the king’ or members of the royal family.

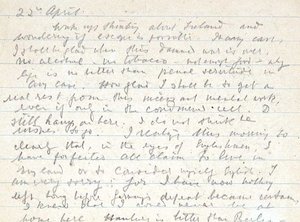

Image 4 of 4

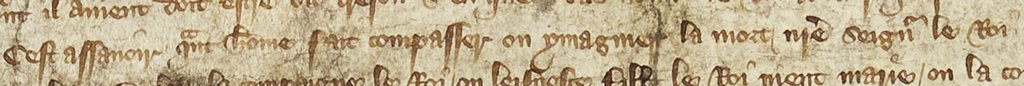

Other treasonous acts included ‘adhering to the king’s enemies’, such as working with foreign agents against the monarch.

Why this record matters

Date: January 1352

The concept of treason is timeless. Before the mid-1300s, its definition was dangerously flexible in England. Accusations of treason were used to crush rebellion and shatter rival factions competing for power at court. The definition of treason was first written into law at the request of Parliament in 1352, in response to fears that the king could arbitrarily charge his subjects with treason. The Treason Act protected the king, his bloodline and his officials. It also protected the king’s subjects by defining exactly which actions were treason and the work of a traitor.

The 1352 Treason Act fixed the meaning of treason for the first time. The definition of high treason, threatening the life of the king, his family or his authority, was recorded on this parchment roll in French, the medieval language of law. It was stored with other records of state in the Tower of London. To medieval minds it was established in 1351, as their new year began on 25 March, but most historians modernise the date to 1352.

The definition of treason did not, however, remain static. The act made provision for future cases of treason beyond what could be imagined at the time, and would be expanded to include religious treasons, treasonous thoughts, political plots, revolutionary movements and subversion against the state. It would frame some of the most monumental moments in English history, from the Gunpowder Plot to the execution of King Charles I.

The Treason Act has been revised and supplemented time and again over the last 670 years. The exact legal meaning of treason has shifted and reset, adapting to suit the needs and fears of those in power. Despite these changes, the core elements of the 1352 Treason Act remain in law today. You can access the current version of it here.

Modern legislation has taken the place of the Treason Act since it was last tested in court in 1946, including the 1989 Official Secrets Act, the 1998 Human Rights Act and the 2000 Terrorism Act. Although it is no longer used as the legal basis for treason trials, the 1352 act still holds a huge emotional, historical, and legal weight. Charges of ‘treason’ and ‘traitor’ remain powerful terms often weaponised at moments of crisis, detached from their legal definition, but rooted in betrayal.

Blogs and podcasts

-

Blog: Treason and the execution of Charles I

By Daniel Gosling – 30 January 2023

Examine how Charles I’s executioners used the language of treason to prosecute the king, and how treason laws were subsequently used during the Commonwealth period (1649-1660).

-

Blog: ‘Compassing and imagining’ – Treasonous words

By Euan Roger – 12 January 2023

What does 'compassing and imagining' the death of the king, his queen, or their eldest son mean? We look into instances where words, speech and writings might become treasonous.

-

Podcast: Treason – People, Power and Plot

By The National Archives – 10 November 2022

In this first episode of our three-part treason mini-series, we explore attempts to kill the monarch in the 16th and 19th centuries and their impacts on the British legal system.