Employing migrant workers

Imperial Typewriters was founded in 1908 by Hidalgo Moya, an American-Spanish engineer. It was bought by an American company, Litton Industries, in 1966, which focused on recruiting migrant workers from India, Pakistan, and the Caribbean. After Ugandan president Idi Amin expelled 60,000 South Asians from Uganda in 1972, many fled to Britain and found work, including at Imperial Typewriters.

The factory’s management viewed migrant workers as cheap labour. As Ron Ramdin notes, of the 1,600 workers employed at the factory, around 1,100 were Asian. Significant numbers of Asian women were also employed. Assumptions concerning gender and race at the time meant they were seen as passive, and therefore ideal workers.

Going on strike

The 1970s saw numerous strikes across Britain, many led by migrant workers standing up for their rights and demanding equality. The 1973–75 recession hit the manufactory industry hard, and some, including Midlands based MP for Wolverhampton South West Enoch Powell, blamed migrants for the economic crisis.

Whilst the South-Asian-women-led Grunwick dispute of 1976 is well known, the Imperial Typewriters strike predates it and emphasised the injustices experienced by migrant workers to a national audience.

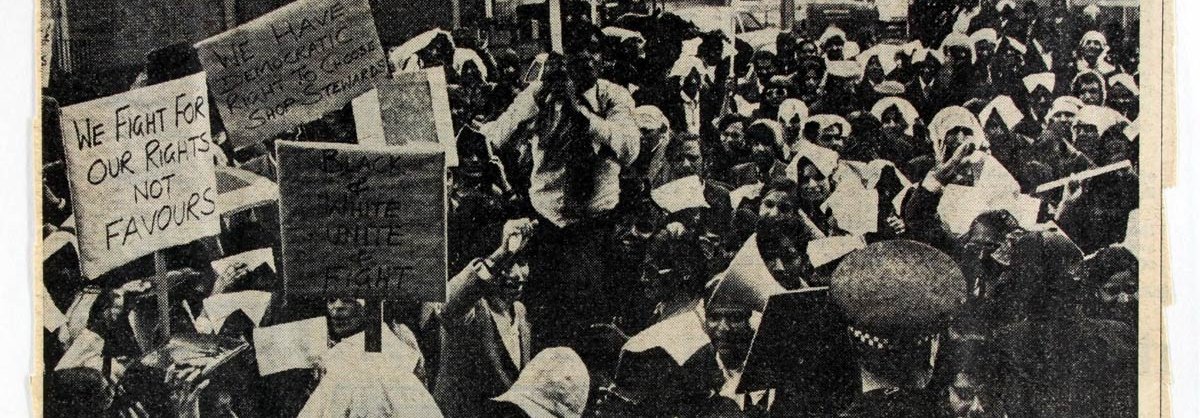

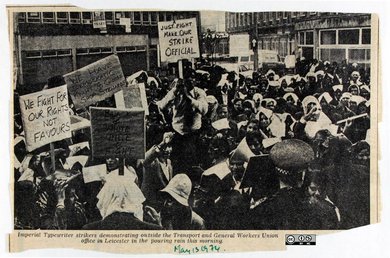

On May Day 1974, 300 workers from four factories in Leicester took part in a walk out, including 39 migrant workers from Imperial Typewriters. Although workers from the other three firms soon went back to work, individuals from Imperial Typewriters remained on strike, and soon this figure rose to over 500 workers.

The dispute centred on limited promotion opportunities for migrant workers and unpaid bonuses, in addition to the lack of support from their union, the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU).

Leicester Mercury article from 5 May 1974, reporting on the Imperial Typewriter Company industrial dispute, 1974. Credit: University of Leicester

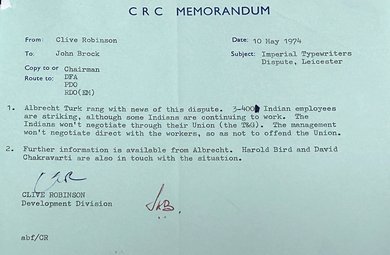

The TGWU refused to make the strike official and George Bromley, the union’s district secretary, argued that the workers had no legitimate grievances. As a memorandum dated 10 May discusses, this caused difficulties in the negotiation process. Those on strike were not able to negotiate through the union, and management would not negotiate directly with the workers to avoid offending the union.

The actions of the TGWU demonstrates the union’s hostility towards migrant workers, and the racist attitudes held by many union officials. These workers were fighting racism both from their employers and the body that was designed to support them through grievances.

Transcript

CRC Memorandum

From: Clive Robinson

To: John Brock

Date: 10 May 1974

Subject: Imperial Typewriters Dispute, Leicester

Copy to or route to:

Chairman

DFA

PDO

RDO (EM)

- Albrecht Turk rang with news of this dispute. 3-400 Indian employees are striking, although some Indians are continuing to work. The Indians won’t negotiate through their Union (the T&G). The management won’t negotiate direct with the workers, so as not to offend the Union.

- Further information is available from Albrecht. Harold Bird and David Chakravarti are also in touch with the situation.

Clive Robinson

Development Division

abf/CR

CRC Memorandum

From: Clive Robinson

To: John Brock

Date: 10 May 1974

Subject: Imperial Typewriters Dispute, Leicester

Copy to or route to:

Chairman

DFA

PDO

RDO (EM)

- Albrecht Turk rang with news of this dispute. 3-400 Indian employees are striking, although some Indians are continuing to work. The Indians won’t negotiate through their Union (the T&G). The management won’t negotiate direct with the workers, so as not to offend the Union.

- Further information is available from Albrecht. Harold Bird and David Chakravarti are also in touch with the situation.

Clive Robinson

Development Division

abf/CR

Memorandum from Clive Robinson to John Brock, 10 May 1974. Catalogue reference: CK 3/31

Over time, the strike also focused on the racial exploitation of migrant workers more broadly, such as the preferential treatment of white workers and the election of white shop stewards. Strikers also had to face prejudice from employees not on strike and were targeted by members of the fascist National Front.

Women workers played a central role in the strike and debunked the myth that Asian women were passive. The Morning Star noted that ‘About half of the 400 or so strikers were women, and they have now formed a women’s group which will remain in existence once they have resumed work.’

Transcript

150 Asian Strikers Restart

By Beatrix Campbell

The Asian strikers at Imperial Typewriters in Leicester were pleasantly surprised yesterday when more strikers than had been expected got a start on the first day of their return to work.

The Asians’ 12-week stoppage ended when the management agreed to reinstate them as far as possible in their own jobs. Where this is not possible the strikers will not experience any downgrading.

About 150 strikers went back to work yesterday, and they are hopeful that the phased return, which was expected to take two weeks will now only take about a week.

About half of the 400 or so strikers were women, and they have now formed a women’s group which will remain in existence once they have resumed work.

Unity needed

This group will function within the structure of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, of which they are all members and will help women workers raise problems and grievances with shop stewards and officials.

While many of the strikers were returning to work, about 400 of the white workers at the factory held a meeting and decided on a policy of non-co-operation with the Asians.

But the strike committee stressed that the Asians wanted unity of the working class. “We are going back to work committed to the unity of all workers, black and white,” said the strike committee yesterday.

Morning Star 24.7.74

150 Asian Strikers Restart

By Beatrix Campbell

The Asian strikers at Imperial Typewriters in Leicester were pleasantly surprised yesterday when more strikers than had been expected got a start on the first day of their return to work.

The Asians’ 12-week stoppage ended when the management agreed to reinstate them as far as possible in their own jobs. Where this is not possible the strikers will not experience any downgrading.

About 150 strikers went back to work yesterday, and they are hopeful that the phased return, which was expected to take two weeks will now only take about a week.

About half of the 400 or so strikers were women, and they have now formed a women’s group which will remain in existence once they have resumed work.

Unity needed

This group will function within the structure of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, of which they are all members and will help women workers raise problems and grievances with shop stewards and officials.

While many of the strikers were returning to work, about 400 of the white workers at the factory held a meeting and decided on a policy of non-co-operation with the Asians.

But the strike committee stressed that the Asians wanted unity of the working class. “We are going back to work committed to the unity of all workers, black and white,” said the strike committee yesterday.

Morning Star 24.7.74

'150 Asian Strikers Restart', Morning Star, 24 July 1974. Catalogue reference: CK 3/31

There was a continuous presence on the picket line, and workers on strike were financially supported by the members of the community, donations from political organisations such the Birmingham Anti-Racist Committee, and street collections.

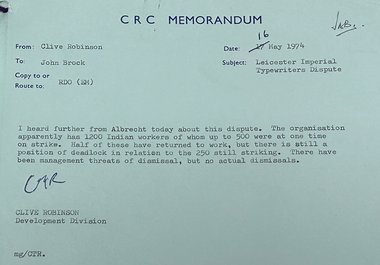

As the strike progressed, some workers returned to the factory. A memorandum dated 16 May states that ‘Half of these have returned to work, but there is still a position of deadlock in relation to the 250 still striking.'

Transcript

CRC Memorandum

From: Clive Robinson

To: John Brock

Date: 16 May 1974

Subject: Leicester Imperial Typewriters Dispute

Copy to or route to: RDO (EM)

I heard further from Albrecht today about this dispute. The organisation apparently has 1200 Indian workers of whom up to 500 were at one time on strike. Half of these have returned to work, but there is still a position of deadlock in relation to the 250 still striking. There have been management threats of dismissal, but no actual dismissals.

Clive Robinson

Development Division

Mg/CTR.

CRC Memorandum

From: Clive Robinson

To: John Brock

Date: 16 May 1974

Subject: Leicester Imperial Typewriters Dispute

Copy to or route to: RDO (EM)

I heard further from Albrecht today about this dispute. The organisation apparently has 1200 Indian workers of whom up to 500 were at one time on strike. Half of these have returned to work, but there is still a position of deadlock in relation to the 250 still striking. There have been management threats of dismissal, but no actual dismissals.

Clive Robinson

Development Division

Mg/CTR.

Memorandum from Clive Robinson to John Brock, 16 May 1974. Catalogue reference: CK 3/31

Race Relations Board Investigation

Many details about the strike, including information related to the picket line and workers' personal experiences of the strike, are not captured in the government records we hold. Nonetheless, records at The National Archives offer an insight into the Race Relations Board’s visit to the factory during the strike. The Race Relations Board was established under the 1965 Race Relations Act, and dealt with complaints of racial discrimination.

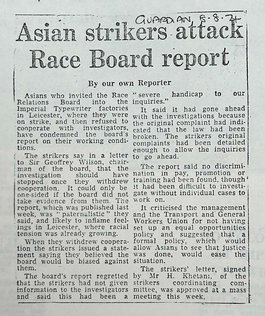

Workers on strike initially invited the Race Relations Board to investigate working conditions at the factory, but later refused to co-operate. An article in The Guardian reported that ‘they believed the board would be biased against them.’ After withdrawing their co-operation, they thought the investigation should not have gone ahead, as ‘it could only be one-sided if the board did not take evidence from them.’

Partial transcript

Asian strikers attack Race Board report

By our own Reporter

Asians who invited the Race Relations Board into the Imperial Typewriter factories in Leicester, where they were on strike, and then refused to cooperate with investigators, have condemned the board’s report on their working conditions.

The strikers say in a letter to Sir Geoffrey Wilson, chairman of the board, that the investigation should have stopped once they withdrew cooperation. It could only be one-sided if the board did not take evidence from them. The report, which was published last week, was “paternalistic” they said, and likely to inflame feelings in Leicester, where racial tension was already growing.

When they withdrew cooperation the strikers issued a statement saying they believed the board would be biased against them.

The board’s report regretted that the strikers had not given information to the investigators and said this had been a “severe handicap to our inquiries”.

It said it had gone ahead with the investigations because the original complaint had indicated that the law had been broken. The strikers original complaints had been detailed enough to allow the inquiries to go ahead.

The report said no discrimination in pay, promotion or training had been found, though it had been difficult to investigate without individual cases to work on.

It criticised the management and the Transport and General Workers Union for not having set up an equal opportunities policy...

The Guardian 8.8.74

Asian strikers attack Race Board report

By our own Reporter

Asians who invited the Race Relations Board into the Imperial Typewriter factories in Leicester, where they were on strike, and then refused to cooperate with investigators, have condemned the board’s report on their working conditions.

The strikers say in a letter to Sir Geoffrey Wilson, chairman of the board, that the investigation should have stopped once they withdrew cooperation. It could only be one-sided if the board did not take evidence from them. The report, which was published last week, was “paternalistic” they said, and likely to inflame feelings in Leicester, where racial tension was already growing.

When they withdrew cooperation the strikers issued a statement saying they believed the board would be biased against them.

The board’s report regretted that the strikers had not given information to the investigators and said this had been a “severe handicap to our inquiries”.

It said it had gone ahead with the investigations because the original complaint had indicated that the law had been broken. The strikers original complaints had been detailed enough to allow the inquiries to go ahead.

The report said no discrimination in pay, promotion or training had been found, though it had been difficult to investigate without individual cases to work on.

It criticised the management and the Transport and General Workers Union for not having set up an equal opportunities policy...

The Guardian 8.8.74

'Asian strikers attack Race Board Report', The Guardian, 8 August 1974. Catalogue reference: CK 3/31

The article went on to discuss the Board’s findings: ‘no discrimination in pay, promotion or training had been found..[but it] criticised the management and the Transport and General Workers Union for not having set up an equal opportunities policy and suggested that a formal policy, which would allow Asians to see that justice was done, would ease the situation.’

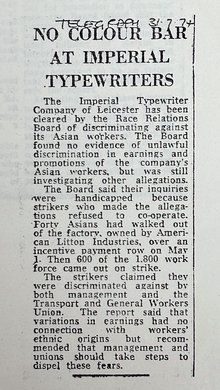

Numerous local and national newspapers reported on the outcome of the report, with The Telegraph running the headline ‘No Colour Bar at Imperial Typewriters’. As the racial prejudice experienced by migrant workers was largely ignored, this reflects the wider culture of discrimination towards migrant workers.

Transcript

No Colour Bar at Imperial Typewriters

The Imperial Typewriter Company of Leicester had been cleared by the Race Relations Board of discriminating against its Asian workers. The board found no evidence of unlawful discrimination in earnings and promotions of the company’s Asian workers, but was still investigating other allegations.

The Board said their inquiries were handicapped because strikers who made the allegations refused to co-operate. Forty Asians had walked out of the factory, owned by American Litton Industries, over an incentive payment row on May 1. Then 600 of the 1,800 work force came out on strike.

The strikers claimed they were discriminated against by both managements and the Transport and General Workers Union. The report said that variations in earning had no connection with workers’ ethnic origins but recommended that management and unions should take steps to dispel these fears.

Telegraph 31.7.74

No Colour Bar at Imperial Typewriters

The Imperial Typewriter Company of Leicester had been cleared by the Race Relations Board of discriminating against its Asian workers. The board found no evidence of unlawful discrimination in earnings and promotions of the company’s Asian workers, but was still investigating other allegations.

The Board said their inquiries were handicapped because strikers who made the allegations refused to co-operate. Forty Asians had walked out of the factory, owned by American Litton Industries, over an incentive payment row on May 1. Then 600 of the 1,800 work force came out on strike.

The strikers claimed they were discriminated against by both managements and the Transport and General Workers Union. The report said that variations in earning had no connection with workers’ ethnic origins but recommended that management and unions should take steps to dispel these fears.

Telegraph 31.7.74

'No Colour Bar At Imperial Typewriters', The Telegraph, 31 July 1974. Catalogue reference: CK 3/31

Returning to work

After accepting a deal devised by the strike coordinating committee, the factory management, the TGWU, and the Department of Employment conciliators, those on strike went back to work after 14 weeks. Migrant workers on strike also ‘issued a statement in which they called for solidarity between black and white workers within the trade union movement.’

Within a few months, the factory closed and workers at Imperial Typewriters were made redundant. The 1973–75 recession resulted in the closure of numerous factories in Leicester and across Britain.

Despite the factory’s closure, the Imperial Typewriters dispute raised awareness of the racist discrimination faced by migrant workers at the factory to a national audience. It also influenced subsequent strikes involving migrant workers in the 1970s, including the Grunwick strike.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Imperial Typewriters dispute

- Date

- 1974–1975