The Huey Fong: Hong Kong's 1979 refugee crisis

In December 1978, over 3,000 Vietnamese refugees aboard a cargo ship were refused entry to Hong Kong. Our records tell the story of the tense standoff that took place, which left the desperate passengers stranded at sea.

Important information

The following article contains descriptions of upsetting conditions faced by Vietnamese refugees in the late 1970s and follows a story of human trafficking.

A boat emerges

The week before Christmas 1978, a cargo ship named the Huey Fong contacted Hong Kong authorities requesting permission to enter its waters. Aboard were over 2,000 refugees it had reportedly rescued off the Vietnamese coast seeking shelter.

Records at The National Archives reveal the complicated story that would unfold over the next 34 days, with its roots in the 20-year struggle between the communist forces in the North of Vietnam, and the anti-communist South.

Two refugees aboard the Huey Fong. Permission for The National Archives to use this image has been kindly granted by Roderick Colson. However, we do not know much about those pictured.

Vietnam War

Asia became a major site of conflict during the Cold War, with the Soviet Union and the United States (US) fighting proxy wars in the region. This included the Vietnam War, which concluded on 30 April 1975 when communist forces took control of the southern capital of Saigon (renamed Ho Chi Minh City).

After the war, those who had been on the side of the South faced retribution, poverty, and repression. The US government assisted in the evacuation and resettlement of people who worked with them, but many others had to find their own way to leave the country, often at great risk.

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR or United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) estimated that hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese attempted to cross the South China Sea in a desperate attempt to reach safety. Often in overcrowded and unsuitable vessels, they were targeted by pirates and at risk of drowning. Many did not survive the journey. These refugees were called ‘boat people’ in the press and in government records, but this term fails to capture the complex human stories and the different circumstances of departure for each individual.

Although not directly involved in the Vietnam War, Britain did play a role in the conflict. Following a temporary ceasefire in 1954, Britain assisted the evacuation of refugees from North to South Vietnam. As the conflict developed, Vietnamese refugees sought safety in Hong Kong – then a British colony – situated some 700 miles north across the South China Sea.

According to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), by 1978, over 5,000 Vietnamese refugees were awaiting resettlement in Hong Kong. They joined thousands of Chinese refugees fleeing political persecution following Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution.

The standoff

On 18 December 1978, the FCO in London received a message from the Governor of Hong Kong, Murray MacLehose. He reported a Panamanian registered merchant ship, the Huey Fong, was seeking permission to enter Hong Kong. Aboard were around 2,000 Vietnamese refugees that the crew said had been rescued at sea. At the time, it was maritime practice for ships that rescued refugees at sea to continue to their first port of call, where the survivors would be given shelter until they were resettled.

This was not the first merchant vessel carrying refugees to request permission to land in Hong Kong. Three years previously a Danish container ship, the Clara Maersk, answered a distress signal from a ship called the Truong-Xua. It was taking on water, putting the lives of the 3,628 refugees aboard at risk. Everyone was picked up, taken to Hong Kong, and given temporary shelter until they were resettled in the USA, Canada, France, Australia, and Denmark.

Transcript

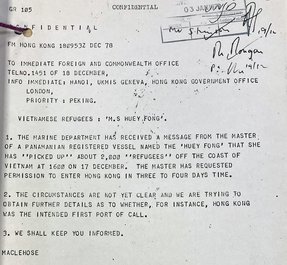

CONFIDENTIAL

FM HONG KONG 180953Z DEC 78

TO IMMEDIATE FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH OFFICE...

VIETNAMESE REFUGEES: 'M.S HUEY FONG'.

- THE MARINE DEPARTMENT HAS RECEIVED A MESSAGE FROM THE MASTER OF A PANAMANIAN REGISTERED VESSEL NAMED THE 'HUEY FONG' THAT SHE HAS "PICKED UP" ABOUT 2,000 "REFUGEES" OFF THE COAST OF VIETNAM AT 1600 ON 17 DECEMBER. THE MASTER HAS REQUESTED PERMISSION TO ENTER HONG KONG IN THREE TO FOUR DAYS TIME.

- THE CIRCUMSTANCES ARE NOT YET CLEAR AND WE ARE TRYING TO OBTAIN FURTHER DETAILS AS TO WHETHER, FOR INSTANCE, HONG KONG WAS THE INTENDED FIRST PORT OF CALL.

- WE SHALL KEEP YOU INFORMED.

MACLEHOSE

CONFIDENTIAL

FM HONG KONG 180953Z DEC 78

TO IMMEDIATE FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH OFFICE...

VIETNAMESE REFUGEES: 'M.S HUEY FONG'.

- THE MARINE DEPARTMENT HAS RECEIVED A MESSAGE FROM THE MASTER OF A PANAMANIAN REGISTERED VESSEL NAMED THE 'HUEY FONG' THAT SHE HAS "PICKED UP" ABOUT 2,000 "REFUGEES" OFF THE COAST OF VIETNAM AT 1600 ON 17 DECEMBER. THE MASTER HAS REQUESTED PERMISSION TO ENTER HONG KONG IN THREE TO FOUR DAYS TIME.

- THE CIRCUMSTANCES ARE NOT YET CLEAR AND WE ARE TRYING TO OBTAIN FURTHER DETAILS AS TO WHETHER, FOR INSTANCE, HONG KONG WAS THE INTENDED FIRST PORT OF CALL.

- WE SHALL KEEP YOU INFORMED.

MACLEHOSE

Message from Hong Kong Governor Murray MacLehose to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, dated 18 December 1978. Catalogue reference: FCO 58/1457

Governor MacLehose was suspicious of the story provided by the Huey Fong’s Master, Shu Wen-Shin. Doubts grew when the authorities established that the ship had been about 200 miles east of Saigon when it sent its message asking permission to enter Hong Kong waters. If those aboard required immediate assistance, Manila or Singapore would have been closer.

Then, investigations by Australian authorities found 30 hours of unaccounted sailing time. It appeared the vessel had not rescued its passengers at sea, but had picked them up at Saigon and trafficked them out of Vietnam, exploiting their vulnerable position for profit.

The Hong Kong authorities replied to the ship’s master refusing permission to enter. On 22 December, the Huey Fong sent a second message saying it was still on its way to Hong Kong and that the condition of the refugees was deteriorating. They were again refused entry and told to continue to their scheduled next port of call in Taiwan. But early in the morning of 23 December, the ship was intercepted just outside Hong Kong waters, where it dropped anchor.

Conditions on board

Concerned about setting a precedent for future traffickers, the authorities continued to deliberate the disembarkation of refugees. Meanwhile, conditions for the refugees aboard only worsened.

During the day of the 23 December, John Turner from the Royal Hong Kong Marine Police boarded the Huey Fong:

The conditions on board the ship were awful. Upon opening the hatches the stench was terrible. Women and children obviously very sick. And there was a complete lack of medical facilities.

John Turner

Turner talked to those on board with the help of an English-speaking refugee. Before long, the story offered by the crew crumbled.

Via our self-appointed interpreter I spoke to some of the Vietnamese. Their stories about their journey were confused, they didn’t ring true, and didn’t make much sense. Someone had obviously contrived to get everyone to tell the same story of a rescue on the seas by a brave Taiwanese skipper, but the stories were different.

John Turner

The decision was made to immediately supply food and water, and to airlift those most in need to hospital. HMS Wasperton’s log shows two doctors were also brought aboard.

Transcript

The Scale of Dry rations Provided by the Social Welfare Department

The dry ration for one person a day (2 meals) supplied to the Huey Fong was a follows:

- Biscuits or bread – 4 oz.

- Biscuits – 4 oz.

- Sweet biscuits – 4 oz.

- Tinned fish – 3 oz.

- Tinned meat – 3 oz.

- Tinned vegetables – 4 oz.

- Orange – 5oz.

- Shelled cooked peanut – 1 oz.

- Butter – 1/2 oz.

- Red tea – 1/2 oz.

- Sweetened condensed milk – 3 oz.

2. The Senior Dietitian of Q.E.II. was consulted about this diet, which contained 2,388 calories and 70.4 grams protein.

The Scale of Dry rations Provided by the Social Welfare Department

The dry ration for one person a day (2 meals) supplied to the Huey Fong was a follows:

- Biscuits or bread – 4 oz.

- Biscuits – 4 oz.

- Sweet biscuits – 4 oz.

- Tinned fish – 3 oz.

- Tinned meat – 3 oz.

- Tinned vegetables – 4 oz.

- Orange – 5oz.

- Shelled cooked peanut – 1 oz.

- Butter – 1/2 oz.

- Red tea – 1/2 oz.

- Sweetened condensed milk – 3 oz.

2. The Senior Dietitian of Q.E.II. was consulted about this diet, which contained 2,388 calories and 70.4 grams protein.

List of daily dry rations for one person supplied to the Huey Fong. Catalogue reference: FCO 58/1747

The master of the Huey Fong continued to ignore instructions to sail to his next scheduled port of call, and the Hong Kong authorities continued to refuse to allow the passengers to disembark. The stalemate carried on through Christmas and into January of 1979.

Transcript

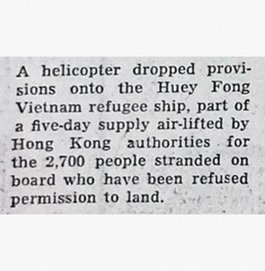

A helicopter dropped provisions onto the Huey Fong Vietnam refugee ship, part of a five-day supply air-lifted by Hong Kong authorities for the 2,700 people stranded on board who have been refused permission to land.

A helicopter dropped provisions onto the Huey Fong Vietnam refugee ship, part of a five-day supply air-lifted by Hong Kong authorities for the 2,700 people stranded on board who have been refused permission to land.

News story on provisions being brought aboard the Huey Fong, The Guardian, 9 January 1979. Catalogue reference: FCO 58/1746

Global responses

The plight of the refugees began to receive international attention. The local UNHCR representative, Angelo Rasanayagam, gave a written undertaking that if the Huey Fong sailed to Taiwan, assistance would be provided through third parties. Additionally, the American authorities were asked to exert what influence they could on the Taiwanese government to accept the ethnic Chinese of the group. On 3 January 1979, Reuters reported Taiwan would not accept the refugees.

Governor MacLehose wrote to the FCO repeating the official view that the Huey Fong was part of an 'organised racket' that others might copy if seen to be successful. Both the Hong Kong authorities and UN officials 'felt very strongly that we must take all possible steps to deter others from entering this business.'

Further press attention led to an offer from Frankfurt-on-Main to resettle 250 people. Yet with so many refugees already in Hong Kong, the authorities felt it was wrong to prioritise resettling those aboard the Huey Fong.

By the middle of January it became clear that the refugees aboard the Huey Fong numbered 3,383 – exceeding original estimates of 2,700.

Offers to resettle them continued with the US offering to take 1,000 refugees by mid-February and a further 600 by the end of March. New Zealand offered to resettle 600 people and the UK Home Secretary, David Owen, agreed to admit 1,000 from the refugee resettlement queue in Hong Kong and 250 each from camps in Malaysia and Thailand.

Partial transcript

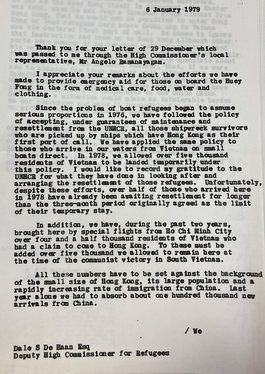

I appreciate your remarks about the efforts we have made to provide emergency aid for those on board the Huey Fong...

Since the problem of boat refugees began to assume serious proportions in 1976, we have followed the policy of accepting, under guarantees of maintenance and resettlement from the UNHCR, all those shipwreck survivors who are picked up by ships which have Hong Kong as their first port of call. We have applied the same policy to those who arrive in our waters from Vietnam on small boats directly. In 1978, we allowed over five thousand residents of Vietnam to be landed temporarily under this policy. I would like to record my gratitude to the UNHCR for what they have done in looking after and arranging the resettlement of those refugees. Unfortunately, despite these efforts, over half of those who arrived here in 1978 have already been awaiting resettlement for longer than the three-month period originally agreed as the limit of their temporary stay.

In addition, we have, during the past two years, brought here by special flights from Ho Chi Minh City over four and a half thousand residents of Vietnam who had a claim to come to Hong Kong. To these must be added over five thousand we allowed to remain here at the time of the communist victory in South Vietnam.

All these numbers have to be set against the background of the small size of Hong Kong, its large population and a rapidly increasing rate of immigration from China.

I appreciate your remarks about the efforts we have made to provide emergency aid for those on board the Huey Fong...

Since the problem of boat refugees began to assume serious proportions in 1976, we have followed the policy of accepting, under guarantees of maintenance and resettlement from the UNHCR, all those shipwreck survivors who are picked up by ships which have Hong Kong as their first port of call. We have applied the same policy to those who arrive in our waters from Vietnam on small boats directly. In 1978, we allowed over five thousand residents of Vietnam to be landed temporarily under this policy. I would like to record my gratitude to the UNHCR for what they have done in looking after and arranging the resettlement of those refugees. Unfortunately, despite these efforts, over half of those who arrived here in 1978 have already been awaiting resettlement for longer than the three-month period originally agreed as the limit of their temporary stay.

In addition, we have, during the past two years, brought here by special flights from Ho Chi Minh City over four and a half thousand residents of Vietnam who had a claim to come to Hong Kong. To these must be added over five thousand we allowed to remain here at the time of the communist victory in South Vietnam.

All these numbers have to be set against the background of the small size of Hong Kong, its large population and a rapidly increasing rate of immigration from China.

Message from Hong Kong Governor, Murray MacLehose, to Foreign and Commonwealth Office dated 6 January 1979 quoting the undertaking from the UNHCR. Catalogue reference: FCO 58/1457

By 17 January, despite final efforts to persuade the master to continue the ship’s journey to Taiwan, the Hong Kong authorities began to prepare to receive the passengers. Two days later, Governor MacLehose reported to the FCO that, at 17:30 local time, the Huey Fong had entered Hong Kong waters and was being directed to a sheltered anchorage. Here, passengers were finally able to disembark.

British responses

Records in our collection show a range of responses from the British public to refugees escaping Vietnam in this period.

In October 1978, a similar story had made UK headlines when a Scottish-owned Merchant Navy ship rescued over 300 Vietnamese from the South China Sea. After two weeks of waiting for a decision from the British government, the refugees were flown to the UK and temporarily housed in Kensington Army barracks, before being resettled elsewhere.

Birmingham City officials wrote to the Home Office offering support to those aboard the Huey Fong should they be resettled in Britain. Homes for between 50 and 60 families were put forward.

Partial transcript

BIRMINGHAM RESCUE PLAN FOR VICTIMS

Daily Telegraph Reporter

Unoccupied council flats in Birmingham may be offered to between 50 and 60 refugee families aboard the Huey Fong.

Leaders of the Conservative-controlled city council meet today to discuss an official approach to the Hong Kong government.

BIRMINGHAM RESCUE PLAN FOR VICTIMS

Daily Telegraph Reporter

Unoccupied council flats in Birmingham may be offered to between 50 and 60 refugee families aboard the Huey Fong.

Leaders of the Conservative-controlled city council meet today to discuss an official approach to the Hong Kong government.

News story on Birmingham City Council's offer of support to those aboard the Huey Fong, The Daily Telegraph, 2 January 1979. Catalogue reference FCO 58/1746

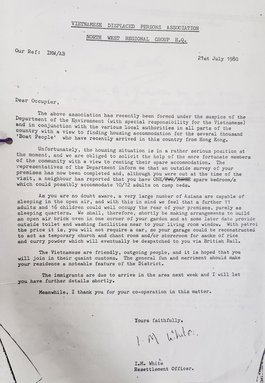

However, the Vietnamese refugees also provided a scapegoat for far-right groups like the National Front, which deliberately spread misinformation about their circumstances and government policy. Hoax letters, some stating Vietnamese arrivals would be resettled in the gardens of elderly residents, were circulated in the Manchester area.

Partial transcript

VIETNAMESE DISPLACED PERSONS ASSOCIATION NORTH WEST REGIONAL GROUP H.Q.

21st July 1980

Dear Occupier,

The above association has recently been formed under the service of the Department of the Environment (with special responsibility for the Vietnamese) and in conjunction with the various local authorities in all parts of the country with a view to finding housing accommodation for the several thousand 'Boat People' who have recently arrived in this country from Hong Kong.

Unfortunately, the housing situation is in a rather serious position at the moment, and we are obliged to solicit the help of the more fortunate members of the community with a view to renting their spare accommodation. The representatives of the Department inform me that an outside survey of your premises has now been completed and .... that you have one spare bedroom which could possibly accommodate 10/12 adults on camp beds.

As you are no doubt aware, a very large number of Asians are capable of sleeping in the open air, and with this in mind we feel that a further 11 adults and 16 children could well occupy the rear of your premises, purely as sleeping quarters. We shall, therefore, shortly be making arrangements to build an open air brick oven in one corner of your garden and at some later date provide outside toilet and washing facilities near to your living room window...

The Vietnamese are friendly, outgoing people, and it is hoped that you will join in their quaint customs.

VIETNAMESE DISPLACED PERSONS ASSOCIATION NORTH WEST REGIONAL GROUP H.Q.

21st July 1980

Dear Occupier,

The above association has recently been formed under the service of the Department of the Environment (with special responsibility for the Vietnamese) and in conjunction with the various local authorities in all parts of the country with a view to finding housing accommodation for the several thousand 'Boat People' who have recently arrived in this country from Hong Kong.

Unfortunately, the housing situation is in a rather serious position at the moment, and we are obliged to solicit the help of the more fortunate members of the community with a view to renting their spare accommodation. The representatives of the Department inform me that an outside survey of your premises has now been completed and .... that you have one spare bedroom which could possibly accommodate 10/12 adults on camp beds.

As you are no doubt aware, a very large number of Asians are capable of sleeping in the open air, and with this in mind we feel that a further 11 adults and 16 children could well occupy the rear of your premises, purely as sleeping quarters. We shall, therefore, shortly be making arrangements to build an open air brick oven in one corner of your garden and at some later date provide outside toilet and washing facilities near to your living room window...

The Vietnamese are friendly, outgoing people, and it is hoped that you will join in their quaint customs.

A hoax letter impersonating a 'Resettlement officer' informing a resident that 11 adult and 16 child Vietnamese refugees were set to 'rent spare accommodation... in the rear of your premises'. Catalogue reference: BS 18/54

In May, four months after the passengers of the Huey Fong entered Hong Kong, the 1979 UK General Election saw the Conservatives come to power. During the campaign, Margaret Thatcher’s administration had pledged to restrict non-European migration.

But within a few weeks the new government was faced with a dilemma. Two British merchant vessels in the South China Sea, the Sibonga and Roachbank, had rescued nearly 1,200 Vietnamese refugees, but their next ports of call had refused permission for them to disembark.

International pressure was placed on the UK to find a resolution, while The Lord Inverforth, who owned the Sibonga and Roachbank, appealed directly to the Prime Minister about the impact on his business. Eventually, the British government agreed to allow the refugees to disembark. Some aboard settled in the UK and were placed in the care of the Ockenden Venture – a refugee charity set-up in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Demands to find a solution

Records from May 1979 show the Prime Minister explored the legal basis for refusing to accept Vietnamese refugees taken on board vessels on the high seas. This included the considering of exiting international maritime obligations. A letter to the Prime Minister from the Law Officers' Department stated:

At our meeting yesterday you asked for my advice on the legal basis for refusal by the UK government to accept Vietnamese refugees taken on board vessels on the high seas.

Catalogue reference: HO 376/200

However, there were concerns that refusing to accept refugees who had been rescued by UK registered vessels would 'weaken our ability to persuade other countries to open their doors to refugees'.

As thousands continued to leave Vietnam, MPs demanded the government find a solution to the crisis. In response, Thatcher claimed the refugee effort in Hong Kong as Britain's own contribution, including the 80,000 people who had already been resettled there – and called for a UN convention to explore international solutions to the crisis. UNHCR’s High Commissioner, Poul Hartling, proposed Britain sign up to the Orderly Departure Programme, committing to resettle more refugees as well as pledging additional finances. Britain agreed and through the programme nearly 20,000 people came from Vietnam to Britain.

To compensate for the arrival of Vietnamese refugees and to ensure they met their election pledge, the British government restricted other forms of immigration through the British Nationality Act of 1981. The first nationality act since 1948, the Right of Abode (to live or work in the UK without any immigration restrictions) could now no longer be acquired by non-British citizens, such as those from the Commonwealth. The government’s withdrawal of domestic spending also put pressure on cash-strapped local authorities attempting to balance the needs of the existing population and the new arrivals.

A policy of dispersal, which aimed to alleviate the impact of refugees in one area, isolated many people from established Vietnamese communities and made accessing services, like language classes, more difficult. Refugees continued to be reliant on voluntary organisations and non-governmental funding.

Aftermath

The Huey Fong case showed the extent of people trafficking for profit during and after the conflict in Vietnam. Three Vietnamese businessmen, all resident in Hong Kong, were identified as the ring leaders behind the Huey Fong case. They were put on trial and found guilty of conspiracy to defraud the Hong Kong government. Each was sentenced to seven years in prison and fined the equivalent of about £5,000. The ship’s master was sentenced to six and a half years in prison, and six of his fellow officers also received prison sentences.

The UNHCR facilitated the resettling of the majority of those aboard the Huey Fong to countries where they already had relatives, with a large number seeking new lives in the US and Australia. Those without overseas connections awaited resettlement, along with thousands of others, living temporarily in camps in Hong Kong.

Records about the Huey Fong at The National Archives have been selected and preserved as part of the official archive for UK government. The voices of refugees aboard are not included, and it can be difficult to get a sense of their experiences from their perspective. In late December 1978, three weeks before passengers aboard were finally able to disembark, refugees displayed a banner on the deck of the Huey Fong requesting permission to stay in Hong Kong, declaring it, 'an example for the support of human right!'

Upon resettlement, many refugees struggled to establish themselves, but others flourished, setting up businesses and contributing to their local communities. The famous Huy Fong Sriracha sauce was created by David Tran who was aboard the ship in 1979 and settled in the US. Looking to other sources provides further insight about people from this period, how they advocated for themselves and forged new lives, despite extremely challenging circumstances.

The first refugee climbing down the Huey Fong's gangway and on to a floating pontoon. Permission for The National Archives to use this image has been kindly granted by Roderick Colson. However we do not know much about those pictured.

Acknowledgments and further reading

This story was inspired by records at The National Archives, and the book Along the Southern Boundary by Les Bird, which contains photographs taken by Hong Kong’s Marine Police from the late 1970s until 1997.

The experiences of Vietnamese refugees, government policy, and the work of voluntary organisations is an under-researched part of our collection. Related record series include BS 18, the papers of the Joint Committee for Refugees from Vietnam (Peterson Committee) from 1979–1982. See also discussions in Records of the Prime Minister’s Office regarding resettlement.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Vietnamese refugees on the MS Huey Fong, Hong Kong

- Date

- 2 January 1978 – 31 December 1978

-

- Title

- Vietnamese refugees on the MS Huey Fong, Hong Kong

- Date

- 1 January 1979 – 31 December 1979

-

- Title

- Vietnamese refugees on the MS Huey Fong, Hong Kong

- Date

- 1 January 1979 – 31 December 1979

-

- Title

- Vietnamese refugees: discussions between Home Office, the Prime Minister and aid agencies

- Date

- 26 May 1979 – 6 June 1979

-

- Title

- Joint Committee for Refugees from Vietnam (Peterson Committee)

- Date

- 1978 – 1982

-

- Title

- Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong; resettlement in UK, part 1

- Date

- 24 May 1979 – 14 Jun 1979

-

- Title

- Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong; resettlement in UK, part 2

- Date

- 11 November 1979 – 13 November 1979