The Beveridge Report

Prior to the Second World War, some in Britain could not afford medical care. Sickness benefits and other forms of insurance existed but illness could impoverish a family.

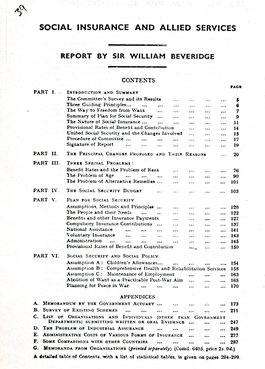

During the war, the economist and former director of the London School of Economics, Sir William Beveridge was commissioned by the Wartime Government to write a report into how to alleviate these social problems. The Beveridge Report released in November 1942, planned to remake Britain after the war by setting up a comprehensive benefits system to end ‘Want’. Underlying this, Beveridge said, would have to be free healthcare. The report – an original copy sent to Prime Minister Winston Churchill is available to view at The National Archives – was hugely influential on the post-Second World War recovery in Britain.

Contents page from William Beveridge's Social Insurance and Allied Services report, showing 'comprehensive health and rehabilitation services' as one of the three assumptions in planning for the post-war abolition of 'Want'.

Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2

With most of the population in favour of Beveridge’s conclusions on free healthcare, the government promised a post-war National Health Service in a 1944 white paper. But while everyone agreed on the aim of universal healthcare, the government cautioned that opinions on ‘the method of achieving it’, were divided.

'Here is our chance to do something big'

Not least was the problem of doctors. Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan became Minister of Health after Labour’s 1945 election victory. Born in Tredegar, Wales, at the age of 47 the former miner was the youngest MP in Clement Attlee’s 1945 Cabinet and one of the most left-wing. He was convinced that the service had to be centralised and doctors state employees, rather than the private businesses they were before.

Many doctors, and the British Medical Association (BMA) which represented them, were unhappy with this, saying they might refuse to participate in the NHS. In December 1945, some of Bevan’s Cabinet colleagues suggested that this might delay the NHS’s launch. Bevan was defiant, he would simply ‘squeeze them out’ with better NHS services. Cabinet meeting minutes held at the National Archives note that Bevan told his colleagues ‘Here is our chance to do something big’.

But the BMA didn’t back down either. In January 1948, just six months prior to the NHS’s publicised launch, they described the service as, ‘so grossly at variance with the essential principles of our profession that it should be rejected absolutely by all practitioners’.

This was, ‘an attempt not merely to seek detailed improvements … but to completely sabotage it’, said Bevan in a government correspondence. Bevan believed attack was the best form of defence. If he could not win over the BMA, he would ‘build up accumulating evidence in the Press and elsewhere’ to win over the public. Bevan called this ‘explanatory work’.

Explaining the NHS

The short cartoon, ‘Your Very Good Health’, released in early 1948 by the Central Office of Information (COI), was part of Bevan’s ‘explanatory work’. It stars ‘Charley’, an everyman. Charley is initially sceptical of the NHS. He has sickness insurance, and while his wife does not, “she’s as strong as a blooming horse she is!”. But soon, after the narrators has shown him the true costs of hypothetical injuries, he’s a convert to cause. The COI staged some 43,000 public information films screenings between 1949 and 1950, so Charley would have been in the public consciousness.

Still from ‘Your Very Good Health’, released by the Central Office of Information to promote the new National Health Service (NHS).

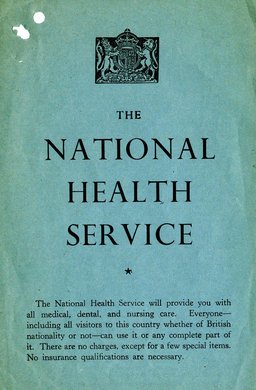

Alongside films there were press adverts and pamphlets. Despite the BMA’s objections, many of these centred on the importance of choosing a GP, ‘your family doctor’. The language is utopian – ‘Anyone can use it – men, women and children. There are no age limits, and no fees to pay’.

But compromises were made – doctors were allowed to see private patients simultaneously, local authorities were given greater autonomy. They produced their own publicity, often similarly celebratory. East Ham in London celebrated the NHS as an ‘epochal event in the conquest of disease and social evil’, before providing photographs, held at The National Archives, of the various therapeutic and care services they would offer.

Transcript

THE NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE

The National Health Service will provide you with all medical, dental, and nursing care. Everyone – including all visitors to this country whether of British Nationality or not – can use it or any complete part of it. There are no charges, except for a few special items. No insurance qualifications are necessary.

THE NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE

The National Health Service will provide you with all medical, dental, and nursing care. Everyone – including all visitors to this country whether of British Nationality or not – can use it or any complete part of it. There are no charges, except for a few special items. No insurance qualifications are necessary.

An example of the pamphlets produced to explain and promote the NHS, August 1948. Catalogue reference: BN 10/32

Launch and demand

The British public quickly made use of the new health service. 95% of the population had registered for the NHS before it launched on ‘the appointed day’, 5 July 1948. Many could now access doctor care and a range of treatments previously beyond their means. Patients on doctors’ registers rose to 30 million. In the first year, over 5 million glasses prescriptions costing 32 million pounds were made. By 1951, 19 million doctor prescriptions were issued per month, up from 7 million in 1947. Four months later in December 1948, Bevan told Cabinet:

After so long a period of carping and bickering, and in spite of a largely hostile Press, the extent and speed with which [the NHS] has 'caught on' with the public is … remarkable.

Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan

But, even then, the NHS struggled with demand. 18,000 doctors had become GPs, but it wasn’t enough yet. More nurses were needed too, with COI and Ministry of Health campaigns increasing their numbers 27% over the next five years.

A newspaper cartoon, collected by the Ministry of Health, 1948–1949. One woman says to another, ‘I had such a lovely dream last night. I was having my hair permed FREE under the National Health’. People were amazed by the medical treatments previously out of reach that were now accessible. The government worried about the cost. Catalogue reference MH 55/907

'The cost of this social innovation'

The cost was a worry, too, particularly dentistry and eyecare. Bevan allowed for some ‘abuses’ both by staff and the public, but said the main cause of expense was ‘people getting things they need but could not afford before … That, then, is the cost of social innovation.’

Partial transcript

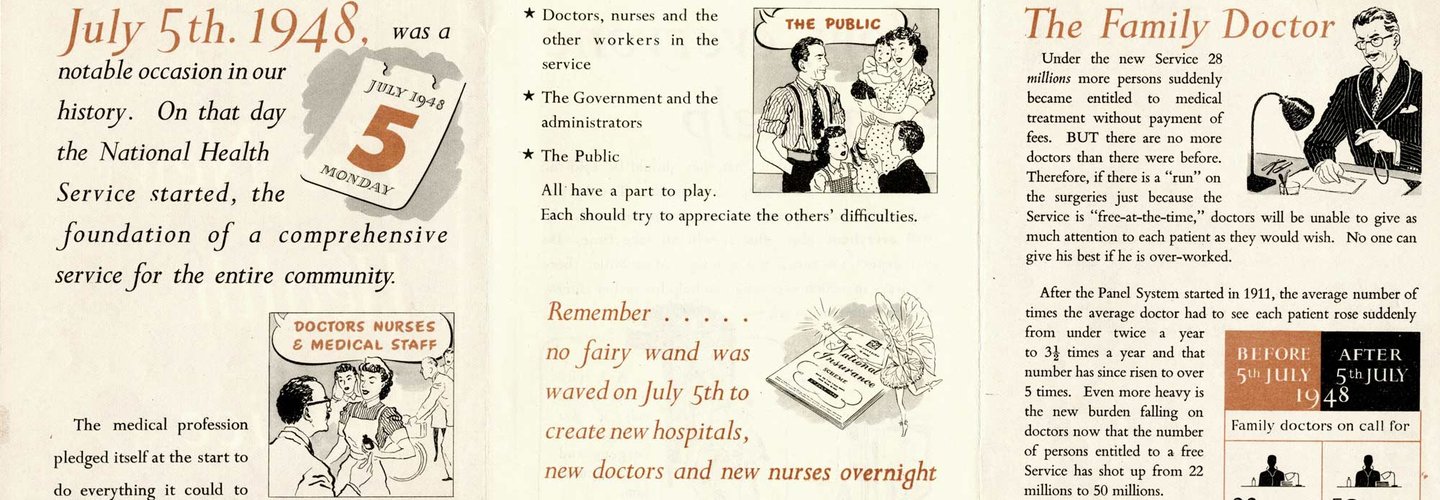

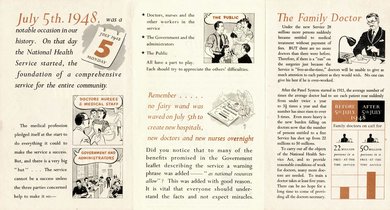

July 5th. 1948, was a notable occasion in our history. On that day the National Health Service started, the foundation of a comprehensive service for the entire community.

The medical profession pledged itself at the start to do everything it could to make the service a success. But, and there is a very big “but”… This service cannot be a success unless the three parties concerned help to make it so:-

- Doctors, nurses and the other workers in the service

- The Government ad the administrators

- The Public

All have a part to play. Each should try to appreciate the others’ difficulties.

Remember….. no fairy wand was waved on July 5th to create new hospitals, new doctors and new nurses overnight.

Did you notice that to many of the benefits promised in the Government leaflet describing the service a warning phrase was added – “as national resources allow”? This was added with good reason. It is vital that everyone should understand the facts and not expect miracles.

A September 1948 pamphlet cautioning the public to ‘not expect miracles’ and behave sensibly after the NHS was established. Catalogue reference: MH 55/965

In response, the ‘explanatory work’ took on another tone. A September 1948 leaflet cautioned an enthusiastic public that, ‘no fairy wand was waved on July 5th’ and advised how to take care of oneself. Bevan was eventually moved from the Ministry of Health, and later resigned as Minister of Labour over cost-saving proposals to introduce charges for dentistry, eyecare, and prescriptions. From its beginning, the NHS had to balance utopian universalism and fiscal concerns.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- The Beveridge Report

- Date

- November 1942 – April 1943

-

- Title

- Proposals for a National Health Service

- Date

- 5 February 1944

-

- Title

- Ministry of Labour & National Insurance: Various Campaigns

- Date

- 1945 – 1965