Record revealed

The Churchill family's 'Blue Book'

Winston Churchill's grandmother's will made reference to a 'Blue Book' that contained instructions on the distribution of her possessions. On her death it caused confusion and disagreement among the family, but also provided an unusually intimate view of this well-known household.

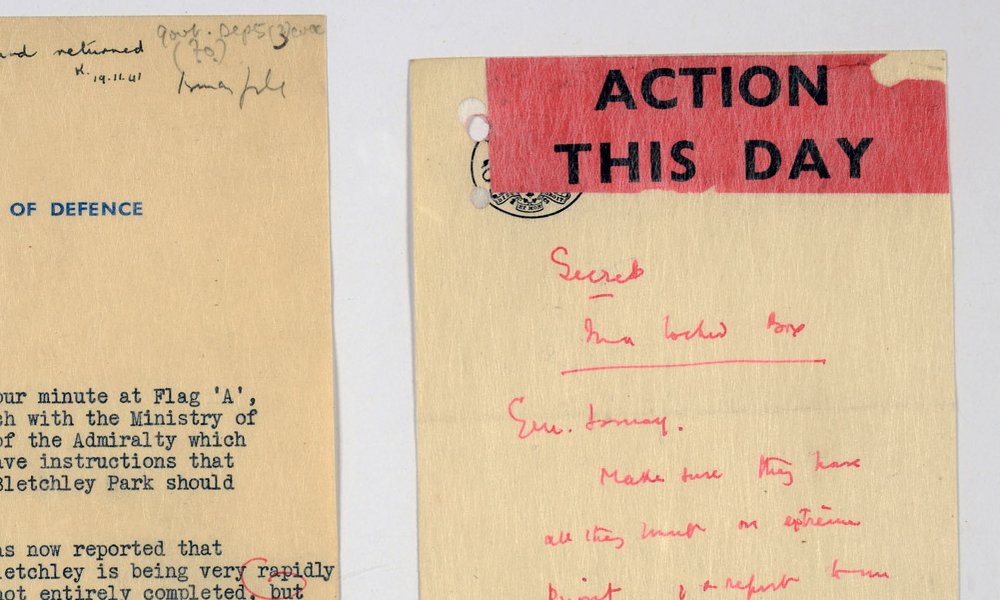

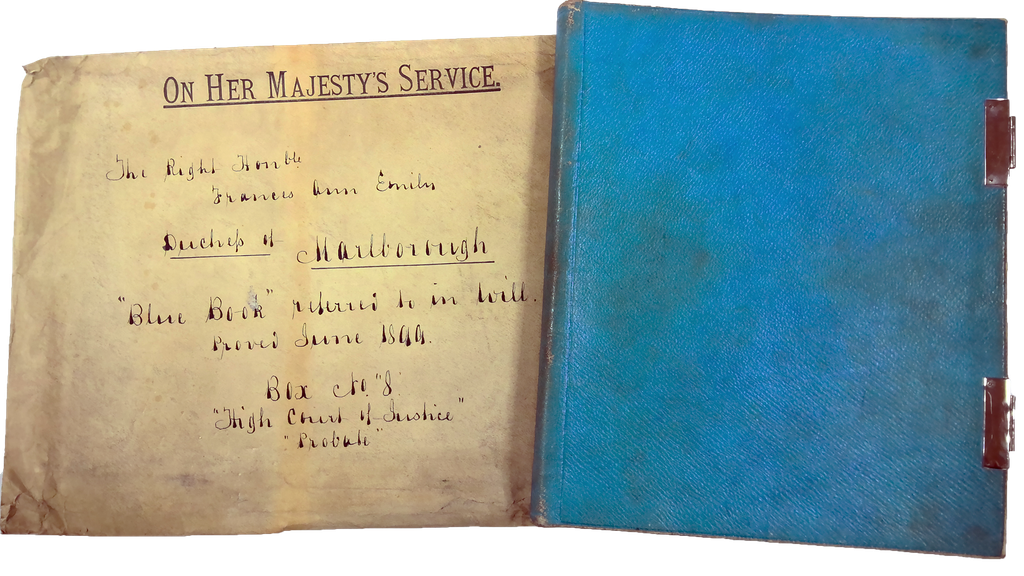

Image 1 of 3

The 'Blue Book' and the envelope in which it was lodged with the court.

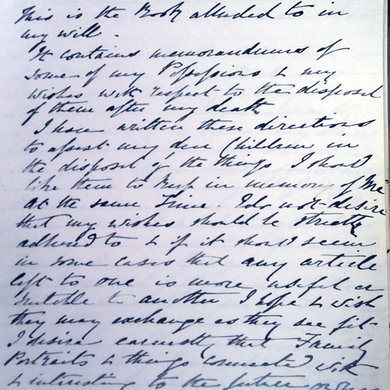

Image 2 of 3

Inscription at the front of the blue book.

Transcript

This book of directions and wishes is private and only to be read by my dear children

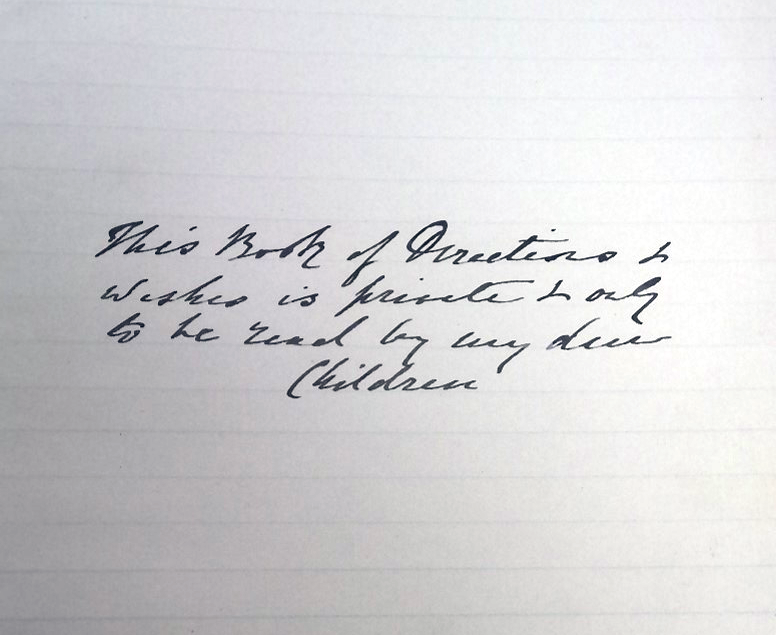

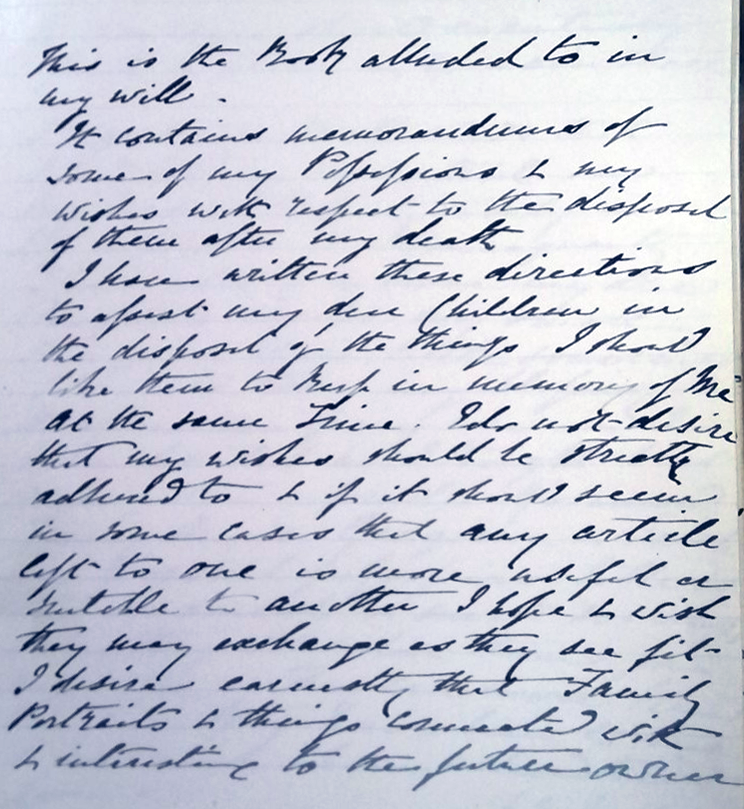

Image 3 of 3

Preface to the 'Blue Book'.

Transcript

This is the Book alluded to in my will.

It contains memorandums of some of my possessions and my wishes with respect to the disposal of them after my death.

I have written these instructions to assist my dear children in the disposal of the things I should like them to keep in memory of me. At the same time, I do not desire that my wishes should be strictly adhered to and if it should seem in some cases that any article left to one is more useful or suitable to another I hope to wish they may exchange as they see fit.

Why this record matters

Date: 1899

This small blue book was submitted, in its accompanying envelope, to the Probate, Divorce, and Admiralty Division of the High Court. It was evidence in a case concerning the administration of the will of Frances Ann Emily Spencer-Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough – the grandmother of Winston Churchill.

The Duchess passed away on 16 April 1899, aged 77. The book consists of a set of directions she wrote in her lifetime, for 'my dear children'. In these ‘memorandums’, she details who she wished to have certain belongings upon her death.

She recorded her instructions in this notebook rather than the will because she 'did not desire that my wishes should be strictly adhered to'. She hoped that 'if it should seem in some cases that any article left to one is more useful or suitable for another', then her six children would 'exchange as they see fit.'

Exploring the objects, people and sentiments mentioned in the notebook, we gain an insight into the author and her family relationships.

Her wishes include:

- her ornamental chinaware and silver are to be shared among her daughters

- her daughter Fanny is to dispose of her carriages and harnesses as she liked

- her daughter Rosamund is to take charge of her wardrobe

- a year's wages are to be allocated for her personal maids and items from her wardrobe as selected by her daughters

- three to six months' salary is to be provided to other servants and distributed at her children's discretion.

The Duchess laments she couldn't do more for her 'dear girls who have been so good and loving to me to the end... God in his goodness may reward them.’ She also mourns the 1895 death of her son Randolph, Winston's father, 'such an unexpected and crushing sorrow that I am quite bewildered and broken hearted'.

Despite these outpourings of love and detailed instructions, the book only exists at The National Archives today because the Duchess’s children could not agree on the administration of her will. Ironically, a parent’s attempt to keep everyone happy may have resulted in family rancour.