Smuggling gangs and coastal policing in 19th-century England

Following the Napoleonic Wars, smuggling became a major concern for the British government. Our records reveal the violent history of smuggling on the south coast of England and the State's attempt to control it.

Shootout at Marsh Bay

At 2am on 2 September 1821, Royal Navy Midshipman Washington Carr led a small party of sailors to patrol the beach at Marsh Bay (now Mildred's Bay), Kent. There he saw two groups of smugglers. A large 'working party' of about 40 men were busily heaving 'tubs' of spirits 'slung with ropes', while a smaller 'scouting party' was armed with muskets to protect those carrying the contraband.

Recognising this as an attempt to smuggle a cargo of untaxed alcohol, Carr fired his pistol into the air to alert his shipmates aboard HMS Severn, a large naval frigate anchored nearby off Margate. He then moved to seize the tubs from the smugglers. However, Carr and his men were met with fierce resistance.

Ten minutes of 'continual firing' ensued, with bullets whistling across the beach. In the fray, the smugglers allegedly cried out, 'Kill the B____rs, Do for the B____rs'! Seaman Thomas Cook was shot in the hip, while Carr found himself bested in hand-to-hand combat by smuggler Daniel Fagg, who dispossessed him of his sword and struck him a backhanded blow. The attack caused Carr to fall 'stunned' and left him with a three-inch cut across his temple.

Carr's men managed to seize 17 tubs in the confusion, but the smugglers kept hold of a further 50. The gang loaded their contraband onto carts (along with several of their wounded comrades) before disappearing into the Thanet marshland.

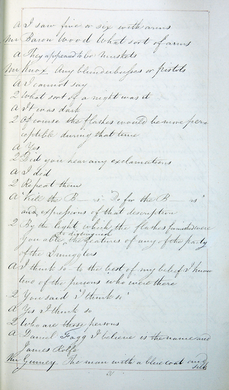

Transcript

Mr Baron Wood: What sort of arms?

Mr Knox: Any blunderbuss or pistols?

A. [i.e. Washington Carr’s answer] I cannot say

Q. What sort of a night was it.

A. It was dark.

Q. Of course, the flashes would be more perceptible during that time

A. Yes

Q. Did you hear any exclamations

A. I did

Q. Repeat them

A. ‘Kill the B[ugger]s, Do for the B[ugger]s’ and expressions of that description.

Q. By the light which the flashes furnished were you able to distinguish the features of any of the part of the Smugglers

A. I think so, to the best of my belief I know two of the persons who were there

Q. You said ‘I think so’

A. Yes, I think so

Q. Who are the persons

A. Daniel Fagg I believe is the name and James Rolfe

Mr Baron Wood: What sort of arms?

Mr Knox: Any blunderbuss or pistols?

A. [i.e. Washington Carr’s answer] I cannot say

Q. What sort of a night was it.

A. It was dark.

Q. Of course, the flashes would be more perceptible during that time

A. Yes

Q. Did you hear any exclamations

A. I did

Q. Repeat them

A. ‘Kill the B[ugger]s, Do for the B[ugger]s’ and expressions of that description.

Q. By the light which the flashes furnished were you able to distinguish the features of any of the part of the Smugglers

A. I think so, to the best of my belief I know two of the persons who were there

Q. You said ‘I think so’

A. Yes, I think so

Q. Who are the persons

A. Daniel Fagg I believe is the name and James Rolfe

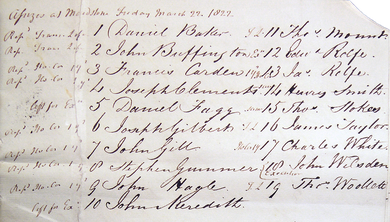

A court transcript from the trial of 19 smugglers at the Maidstone Assizes, 22 March 1822. Catalogue reference: ADM 1/5124/4

The revival of smuggling

The smugglers at Marsh Bay were one of several organised crime groups that sprang up on the south coast of England in the decade or so following the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815).

During the war, particularly following the defeat of the French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), the Royal Navy strictly controlled shipping into and out of Britain. Napoleon's 'Continental System' (which forbade trade with Britain) and the British policy of banning exports to the Napoleonic Empire further choked off trading links with Europe. Although some small-scale smuggling continued, the circumstances of the war tended to reduce the impact of the contraband trade on British shores.

A map of the south coast of England, 1680. Catalogue reference: MPI 1/463

With the coming of peace in 1815, however, Lord Liverpool's government (1812–1827) found the re-opening of continental ports, the sudden return of some 300,000 soldiers and sailors from the wars, and the depressed state of the domestic economy combined to produce a significant revival of organised smuggling.

In February 1816, the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury issued a minute highlighting the 'enormous increase' in smuggling. It was believed to have been exacerbated by the 'daring character of the Smugglers let loose by the termination of the war'.

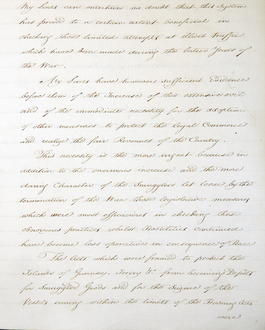

Transcript

My Lords have however sufficient Evidence before them of the Increase of this extensive evil and of the immediate necessity for the adoption of other measures, to protect the legal Commerce and realize the fair Revenues of the Country.

This necessity is the more urgent because in addition to the enormous increase and the more daring Character of the smugglers let loose by the termination of the war those legislative measures which were most efficacious in checking these obnoxious practices whilst hostilities continued have become less operative in consequence of Peace.

My Lords have however sufficient Evidence before them of the Increase of this extensive evil and of the immediate necessity for the adoption of other measures, to protect the legal Commerce and realize the fair Revenues of the Country.

This necessity is the more urgent because in addition to the enormous increase and the more daring Character of the smugglers let loose by the termination of the war those legislative measures which were most efficacious in checking these obnoxious practices whilst hostilities continued have become less operative in consequence of Peace.

A Treasury Minute issued 2 February 1816 regarding the recent increase in smuggling and the 'daring character' of the smugglers. Catalogue reference: T 29/139, f. 473

One obvious solution to the problem was dramatically reducing the high taxes on foreign luxuries like brandy. However, at a moment when government finances were already strained to meet the costs of the recent war, cuts to customs and excise duties were seen as 'utterly impractical'. Instead, the British government opted for stricter coastal policing to 'increase the danger and hazard of this traffic to the greatest practical extent'.

The Royal Navy and the Coast Blockade

To combat smuggling, the government mobilised the personnel and expertise of its peacetime naval establishment. In addition to manning and commanding 26 naval warships and 48 revenue cutters that cruised British waters looking for smuggling vessels, in 1817 the Admiralty was tasked with organising a ‘Coast Blockade’.

The blockade men had orders to come ashore 'a little after sunset, for the purposes of forming a guard along the coast during the night' and to 'return to their ships in the morning, a few minutes before sun-rise'. The blockade line ran between the North and South Forelands of Kent, but was later extended to cover 150 miles of coast between the Isle of Sheppey and Beachy Head. By January 1822, over 1,500 experienced seamen were attached to HMS Severn to prevent smuggling.

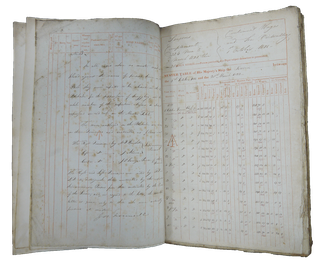

A Muster Table showing the number of men attached to HMS Severn, October 1821–March 1822. Those 'absent on the coast blockade' are marked in red ink and in January 1822 total more than 1,500 men. Catalogue reference: ADM 37/6393

As far as peacetime postings went, the Coast Blockade was a relatively dangerous and difficult duty. In the six months before the Marsh Bay incident, a midshipman, Sydenham Snow, was shot dead at Herne Bay, and a Quartermaster, Richard Woolridge, was killed by smugglers at Folkestone.

The inhabitants of Sussex and Kent appear to have resented the presence of the Coast Blockade. Volunteers were chosen from the Navy on the basis of character and a lack of local connection. This was seen as advantageous for the Admiralty, as it lessened the chances of smugglers befriending or bribing the seamen. However, their presence on shore, and their interference in what many saw as a legitimate smuggling trade, was unpopular with locals who often complained of the expense of maintaining the blockade.

Smuggled goods

Despite their unpopularity (or perhaps constitutive of it), the Coast Blockade made a considerable contribution to policing Britain's southern tax border.

Among the voluminous 'Long Bundles' found among the papers of the Treasury Board, two surviving boxes of documents give details of the seizure of smuggled goods during this period. According to the extracts compiled at Custom House in London, by the mid-1820s, the sailors of the Coast Blockade were making over 500 seizures a year.

The more detailed accounts show that between October 1823 and October 1824, the blockade seized 18,000 gallons of spirits (roughly half of which was gin and half brandy), 1,900 yards of silk, 600 bandanna handkerchiefs, 590 pounds of tobacco, and 1,263 pounds of tea.

Over the same period, the blockade men captured six smuggling luggers, two galleys, one sloop, and 35 smaller boats. They also detained close to 50 smugglers, turning four over to the navy and sending 43 to local jails. The penalty for smuggling for men with experience at sea was five years' service in the fleet. But, for those who used force of arms to resist arrest, the maximum punishment was death.

Early 19th-century coloured etching: A Smuggler shown at different stages of his chosen profession (No date, c.1810). Source: Wellcome Collection, 29590i.

Trial and punishment

So, what of the North Kent Gang?

Following the affray in September 1821, 19 suspects were brought for trial at Maidstone Assizes the following March. Their reputed leader – Stephen Lawrence, a ship's carpenter from Canterbury – was named on the indictment, but remained at large.

Unusually for this period, a full transcript of the trial was produced. As the case involved an armed assault on a midshipman, the Admiralty appears to have sent a clerk from Whitehall to take notes at the trial. These were then bound together.

Bound Volume of the Proceeding of the case of King vs Baker and 18 others, Kent Assizes, Maidstone, 22 March 1822. Catalogue reference: ADM 1/5124/4

In court, the men of the Coast Blockade testified against the smugglers and prosecution lawyers presented physical evidence to the jury. This included muskets and a smuggler's hat shot through with bullet holes.

In his summing up, Judge Baron Wood condemned the 'pernicious' practice of smuggling and sentenced all 19 of the accused to death. They were then removed to prison hulks – decommissioned warships used as makeshift floating prisons – to await their fate.

In a series of letters and private conferences with the Home Secretary, Robert Peel, Judge Baron Wood advised that the four worst offenders (including Daniel Fagg) should be 'left for execution', but that the remaining 15 receive reduced sentences. Five men were eventually transported to Australia. Ten languished aboard the hulks for years before being released, though one of their number, Daniel Baker, died aboard York in 1829.

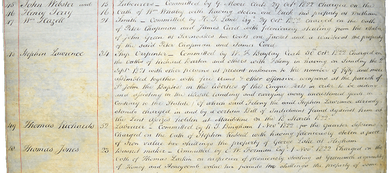

Judge Baron Wood's report on the trial at Maidstone Assizes beginning with an annotated list of convicts, indicating that four men – Daniel Fagg, John Meredith, John Wilsden, and Edward Rolfe – are to be 'left for ex[ecutio]n'. Catalogue reference: HO 17/1/12

On 4 April 1822, four carefully selected smugglers (all suspected of carrying arms at Marsh Bay) were publicly hanged at Penenden Heath, on the outskirts of Maidstone, before an 'immense' crowd of 15,000. They were the last smugglers to be hanged in England.

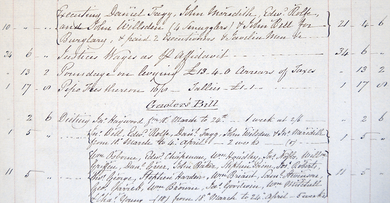

Extract from the Sherriff’s Cravings for the county of Kent, recording the cost of £21, 4s., 6d. for ‘Executing Daniel Fagg, John Meredith, Edw[ar]d Rolfe, and John Willesden (4 Smugglers) & John Bell for Burglary, & paid [to] 2 Executioners and Javelin Men etc.’. Catalogue Reference: T90/170

Meanwhile, Stephen Lawrence was captured by the Coast Blockade on 10 October 1822 while smuggling at Kingsgate Bay. He was tried in December that year for leading the assault against Washington Carr but, with the assistance of two defence lawyers, was acquitted.

Transcript

Stephen Lawrence, 34, Ship Carpenter, Committed by W.F. Bayley last 30 Oct. 1822. Charged on the oaths of Richard Barton and others with Felony in having on Sunday 2nd September 1821 with other persons at present unknown to the number of fifty and more assembled together with fire arms and other offensive weapons at the parish of St John the Baptist in the Liberties of the Cinque Ports in order to be aiding and assisting in the illegal landing and carrying away uncustomed goods contrary to the statute of which said Felony the said Stephen Lawrence already stands charged in and by a certain Bill of Indictment found against him at the Lent Assizes holden at Maidstone on the 18 March 1822.

Stephen Lawrence, 34, Ship Carpenter, Committed by W.F. Bayley last 30 Oct. 1822. Charged on the oaths of Richard Barton and others with Felony in having on Sunday 2nd September 1821 with other persons at present unknown to the number of fifty and more assembled together with fire arms and other offensive weapons at the parish of St John the Baptist in the Liberties of the Cinque Ports in order to be aiding and assisting in the illegal landing and carrying away uncustomed goods contrary to the statute of which said Felony the said Stephen Lawrence already stands charged in and by a certain Bill of Indictment found against him at the Lent Assizes holden at Maidstone on the 18 March 1822.

Stephen Lawrence listed as one of the prisoners to be tried at the special Winter Assizes for Kent in December 1822. Catalogue reference: ASSI 94/1850

Years later, when Lawrence was in his mid-50s, he was convicted of stealing furniture from a neighbour. Though he and his wife petitioned vigorously for a reduced sentence, the Home Secretary rebuffed their appeals. According to the Recorder of Dover, who presided at his trial, Lawrence had 'for many years [been] engaged in smuggling and other lawless transactions and is reputed to have been one of a smuggling party by whom a revenue officer was killed'. Based on this damning assessment, Lawrence was duly transported to New South Wales, Australia, to serve a 10-year term.

The records held at The National Archives reveal the violence and determination of the smuggling gangs and the lengths the government went to clamp down on them. In the south east of England, the Navy's Coast Blockade was vital in preventing smuggling and bringing offenders to justice. In 1831, the blockade was merged with the coast guard. However, it was not until the 1840s, when dramatic reductions in import taxes made smuggling far less profitable, that the gangs ceased to operate on the south coast.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Captain McCulloch's Letter Books – Seizures by the Coast Blockade

- Date

- 1821–1823

-

- Title

- Indictment Files for the Special Assizes for the County of Kent

- Date

- 1822

-

- Title

- Bundle of Petitions relating to the North Kent Gang

- Date

- 22 December 1823

-

- Title

- Criminal Petitions and Reports relating to Stephen Lawrence

- Date

- 1840

-

- Title

- Long Papers, bundle 750, part 1: Smuggling: Customs and Excise reports

- Date

- 1790–1840

Read more

- William J. Ashworth, Customs and Excise: Trade, Production, and Consumption in England, 1640-1845 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- Gavin Daly, ‘English Smugglers, the Channel, and the Napoleonic Wars, 1800-1814', Journal of British Studies, 46.1 (2007) 30-46.

- Renaud Morieux, The Channel: England, France and the construction of a maritime border in the eighteenth Century (Cambridge, 2016).

- Roy Philp, Coast Blockade, The: The Royal Navy's War on Smuggling in Kent and Sussex, 1817-31 (Compton Press, 1999).