A medieval Irish roll with hidden grievances

1284

This roll provides a glimpse into how medieval Ireland was governed, but today plays a starring role in the development of scientific methodologies.

Tucked away at The National Archives is a medieval story of ‘corruption never before seen’. In 1325, officials at the Westminster Exchequer found suspicious mistakes in the account of the treasurer of Ireland and hauled him through the courts. Those accounts remain outstanding to this day.

From 1171, when King Henry II invaded, the island of Ireland came under English lordship. From about 1200 a colonial government in Dublin was set up answering to the English government in Westminster.

On 12 November 1319, the clerks of the English exchequer, the chief financial department of royal government based in Westminster Hall, issued a writ. This was a small strip of parchment commanding Alexander Bicknor, archbishop of Dublin and former treasurer of Ireland, to bring his accounts to London for audit.

Westminster Hall, the surviving heart of the medieval palace which is now the Houses of Parliament. In Bicknor’s time, it was where the law-courts met. The exchequer had rooms opening off it. © House of Commons (CC BY-NC 2.0)

The order took about nine weeks to reach Dublin. On 15 January 1320, Bicknor himself brought it into the Dublin Exchequer, to start the process of gathering his rolls to send them to England.

The clerks both in Dublin and London must have thought that it would be as routine as these things ever were. There would be delays, disputed payments, and queries. But, in 1325, when the audit was almost complete, a metaphorical ticking timebomb lurking in the accounts went off.

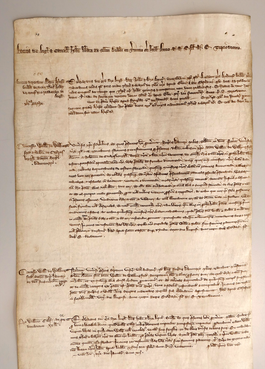

Bicknor was ordered several times to come to London with the documents needed for the audit. This first entry is now at the National Archives of Ireland (EX/1/2, rot. 18 face). Image: National Archives of Ireland and Jessica Baldwin

Bicknor had entirely fabricated some of his documents and around £1,200 – a fortune of well over half a million pounds in today’s currency – was unaccounted for. Bicknor faced imprisonment and ruin, not to say the damnation of his soul.

His cause soon became wrapped up in the crisis surrounding King Edward II. Edward’s reign came to an abrupt but bloodless end in the autumn of 1326, in a coup orchestrated by his estranged wife Queen Isabella and her possible lover Roger Mortimer. Bicknor declared for Isabella and Mortimer against the king. This looked like the right decision by 1329, when he received a full pardon for corrupt practices. But the political winds shifted again in 1330 as Mortimer was swept from power by the young king, Edward III.

Queen Isabella, daughter of the king of France, in a contemporary portrait from her psalter, now in the Bavarian State Library (BSB Cod.gall. 16). Image: Wikimedia Commons

After trying to gain a pardon from Edward III, Bicknor had little political capital to spend on clearing his name. Astonishingly, he did at last obtain a true pardon in 1344. But his forgeries were never fully sorted out and, perhaps more astonishingly, his account as treasurer of Ireland was never closed.

Our evidence for the scandal comes principally in the shape of the rolls of the Dublin Exchequer, the satellite financial institution established on the Westminster model around 1200. Following other accounting and corruption scandals in the late 13th century, exchequer officials in Ireland were periodically required to bring their rolls of receipts and payments made in Ireland to Westminster.

Among them were those financial rolls that were brought to Westminster as part of the Plantagenet kings’ efforts to understand, control and direct activity in Ireland. These original medieval records are copies of those that were kept in Dublin; the treasurer himself and both of his two chamberlains – essentially his seconds-in-command – of the exchequer kept their own set of records. Along with supporting documentation, they roughly cover the two centuries between 1270 and 1473.

This audit process, however, did not eradicate corruption. The surviving rolls for Bicknor’s period in office from 1307 to 1314 are an exercise in chaos. They regularly note payments made in unusual ways, without the usual authorisation by tally stick, including large amounts of taxation receipts. Other tallies, the wooden sticks used to record payments, like a modern till-receipt, were incorrectly made.

Tally sticks were struck as a means of authorising payments. The details were written on the stick and then they were notched and split in half vertically. One half stayed in the exchequer and one was given to the person making or receiving the payment. If there were questions about whether a payment was valid, they could be brought together and matched up.

Some surviving examples of tally sticks. Catalogue reference: E 402/347

Additionally, some records could not be found. In 1328 English officials began to hone in on the central issue: the lands and income that the archbishop had been ordered to seize from the Knights Templar.

Bicknor was accused of mishandling the possessions of the Templars, a military order founded for the Crusades in the Middle East. Their arrest and trial in 1308 was a Europe-wide affair, ordered by Pope Clement V .

It reached Dublin in January 1308, when the English king commanded that the papal order be followed. The Templars held a wide range of lands and churches in Ireland, and when the king’s agents appeared to take possession, they were instructed to record the value of the land, equipment, animals and crops that they found. Then they were supposed to manage the estates carefully, keeping records of what they had done.

Instead, the records were patchy and fragmentary. In 1328, the English treasurer complained that the summary sent to London was ‘insufficient’ and gave a long list of the ways in which they had failed.

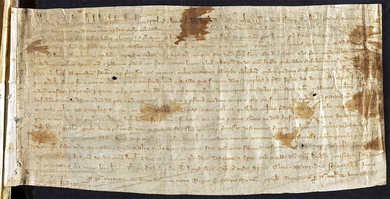

This writ from the English treasurer, Henry Burghersh, started a new process of trying to understand what Bicknor had done. It is sewn to a larger document. Catalogue reference: E 101/239/13

The clerks in Ireland had to scramble to find out what had been done, including working out exactly who had been responsible for managing the estates for 20 years. They asked local men to assemble in juries and swear to what had happened.

Often though, memories were short and details lacking. In the south of Ireland, in County Waterford, they could not even send messengers to assemble any jury, ‘on account of war between certain magnates of the land’ and so did ‘not dare to approach those territories’.

Bicknor’s experience of trying to account for sums gathered and spent in Ireland highlights the difficulties the English government faced there. His response – to forge the authorisation for payments – stood out as shocking. The memoranda rolls, the working memory of the exchequers both in Westminster and Dublin, show the problems of trying to manage government at a distance.

In 1319, the city of Dublin noted that they hadn’t been able to maintain complete tax records because of the need to focus on defence during an invasion led by Edward, brother of the Scottish king, Robert Bruce, four years earlier.

It wasn’t just major crises that made it hard to track finance, though. The routine transfer of personnel meant that records might be mislaid. Accidental fire was also reasonably common as when in 1284, Ireland’s Domesday Book was allegedly lost to a fire in a clerk’s bedroom.

The Dublin Exchequer regularly searched its records to chase up debts, answer queries and authorise actions. The Westminster Exchequer then did the same, and sent messages asking Dublin for more information. Bicknor’s political woes and the process by which he and others were cross-examined about them were recorded in the English memoranda roll.

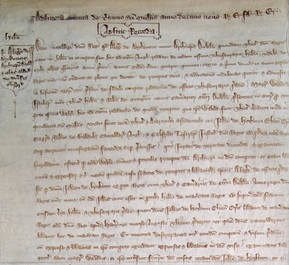

This document on the English memoranda roll is the most complete description of what happened in the Irish exchequer during Bicknor’s time there, but it still leaves questions unanswered. Catalogue reference: E 159/102

This enabled other clerks to look back to see what had happened, what was still unknown, and to try to get his accounts finally approved. That they never were bears testament both to the optimistic thought that they might well one day find all the answers, and to the difficulty of governing medieval Ireland.

When the Public Record Office of Ireland in Dublin succumbed to fire in the opening engagements of the Irish Civil War in June 1922, seven centuries of records detailing government and society in English-ruled Ireland were almost all destroyed. But, despite decades of gloom around this lost archival legacy, there remains an almost inconceivable wealth of material which is now allowing a re-imagining and reconstruction of this lost collection.

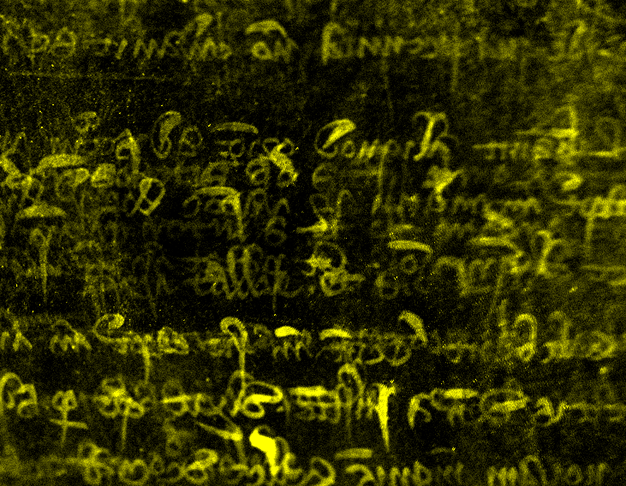

1284

This roll provides a glimpse into how medieval Ireland was governed, but today plays a starring role in the development of scientific methodologies.

We don’t know who in the spring of 1922 asked to see two of the Irish memoranda rolls in the Public Record Office of Ireland, those covering the years 1309–10 and 1319–20. What we do know is that, during the battle and fire which destroyed the Record Office, these two rolls from the reign of Edward II were kept in the strong room, separate from the repository which was blown up. Thus, they escaped the fire which consumed the other records. Now carefully conserved and digitised at The National Archives, Ireland, they provide a fascinating insight into the processes of government, including Bicknor’s misdeeds.

Other replacement materials are found around the world. Since 2016, the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland (VRTI) project hosted at Trinity College Dublin has been working to identify and make available digitally the surviving records, copies made before the fire, and records that should have been in the collections in 1922.

The VRTI is a growing open-access repository of Irish records which now contains over 250,000 digital images and tens of millions of words of searchable text relating to these seven centuries of Irish history. It is an all-island, international research project in which The National Archives is a key partner.