Queer connections: The policing of gay personal adverts in the 1960s

Personal adverts have long provided a way for people to find connections. The 1960s saw the expansion of these adverts in the gay community. But records in our collection show how those published in countercultural paper the International Times became part of a high-profile legal battle.

Important information

This article references attempts to suppress the visibility of gay and bisexual men, as well as institutional homophobia.

Seeking connections

In the 1960s, classified adverts in magazines provided a way for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer individuals to connect and build communities, much like today's dating apps. Gay culture in Britain was slowly becoming more visible. The partial decriminalisation of same-sex acts between men in 1967 marked a significant legal shift, but societal acceptance was more complex. The new law embedded inequalities, treating gay and bisexual men differently with an 'in private' clause, a different age of consent, and an armed forces exemption. Arrests and sentence lengths related to homosexual acts actually increased after the change in law.

Veteran campaigner Antony Gray asked in 1969, ‘Do we make it easy, legally or socially, for homosexuals to meet one another? We do not.’ The Campaign for Homosexual Equality noted that LGBTQ+ individuals, especially those in rural areas, had fewer opportunities and spaces to meet suitable partners.

Classified adverts offered one solution, providing a place for those sidelined in mainstream spaces to find sex and companionship. The rise of anti-establishment magazines created platforms for these adverts. One of the prominent ones to emerge was the International Times.

The International Times

The International Times (IT), founded in 1966, was a leading underground magazine, supported by figures like John Lennon and Pink Floyd. It aimed to be a space for marginalised groups, including hippies, anarchists, and Black Power activists.

The magazine covered international struggles, student protests, London squats, and the music scene, and often represented a pro-drugs stance. Its front pages had striking, psychedelic artworks, provocative text, and an iconic IT girl logo.

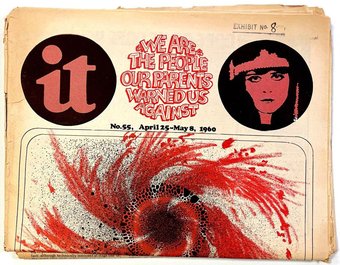

Copies of the International Times, seized in raids on their offices in 1969. Catalogue reference: DPP 2/4670

As the paper grew, so did its small adverts section. Initially focused on services or accommodation, it quickly attracted significant demand for personal connections. The pages welcomed many types of people, removed from the usual shame and stigma they may have faced. IT explained the motivation behind these pages: ‘We run these ads as a service to bring people together who are lonely or who have difficulty meeting one another’ (catalogue reference: DPP 2/4670). They kept the price of these adverts low, seeing them as providing a community space.

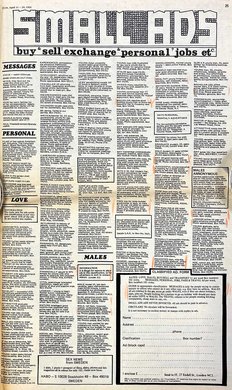

Smalls adverts page from the International Times, including a Males section with highlighted adverts. No 54, April 11-24, 1969. Catalogue reference: DPP 2/4670.

The ‘Males’ section was dominated by gay and bisexual men, with approximately 100 adverts per issue. Other sections featured some adverts between women and some references to trans experiences. These adverts ranged from physical descriptions and sexual preferences to expressions of loneliness and frustration at the difficulty of meeting people. The language used reflected the developing community identity and LGBTQ+ subcultures, with terms like ‘dolly boy’ and ‘bodybuilder.’

YOUNG continental, medium height, brown haired, affectionate, well-built wishes to meet young intelligent man for possible permanent relationship. London area. Letters with photo please.

LEATHER guy (35) would like to meet others under 40 who share his taste for the kinky and unusual. All letters with photo answered.

GAY GIRL, attractive, feminine, late twenties, seeks other gay girl for close friendship. Must be intelligent and attractive.

Example personal adverts from copies of International Times

Many of these listings did lead to people meeting. Receiving 6–13 replies was standard. The magazine eventually added a disclaimer, reserving the right to alter or reject adverts if they were in poor taste or could lead to legal issues.

Complaints

IT reached a growing youth audience excited by the possibilities of the new countercultural scene. Letters were sent to MPs from concerned parents and teachers aware of the publication being sold in schools, youth clubs and colleges. One mother noted, ‘it is a deliberate attempt to corrupt youth to think, feel and believe in, what the Editors and contributors think, feel and believe’ (catalogue reference: DPP 2/4338).

The Director of Public Prosecutions discussed limiting the content through various legislation, from the Post Office Act to the Obscene Publications Act, but repeated attempts to censor the magazine failed. There was also a fear that prosecution would increase publicity and visibility of the publication and could cause backlash articles in IT’s pages. Similar publications of the era, such as Oz, Rolling Stone, Black Dwarf and Red Mole, also attracted police attention.

‘Sinister operations’: the raids

In March 1967, the IT offices were raided and 8,000 editions of the paper were seized. Despite all the build-up investigations, the grounds for prosecution were not strong enough and no charges were made. In 1969, the offices were raided again, focusing on the different angle of gay personal adverts. Over 2,000 copies of different issues were seized, along with correspondence and letters. The magazine circulated an open letter in response and sent a copy directly to the Director of Public Prosecutions. In their letter they note, ‘these sinister operations have begun again’ (catalogue reference: DPP 2/4670).

Partial transcript

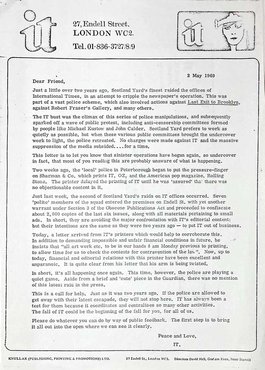

Dear Friend,

Just a little over two years ago, Scotland Yard’s finest raided the offices of International Times, in an attempt to cripple the newspaper’s operation. This was part of a vast police scheme, which also involved actions against Last Exit to Brooklyn, against Robert Fraser’s Gallery, and many others.

The IT bust was the climax of this series of police manipulations, and subsequently sparked off a wave of public protest, including anti-censorship committees formed by people like Michael Kustow and John Calder.

[…]

This letter is to let you know that sinister operations have begun again, so undercover in fact, that most of you reading this are probably unaware of what is happening.

[…]

Just last week, the second of Scotland Yard’s raids on IT offices occurred. Seven ‘polite’ members of the squad entered the premises on Endell St. with yet another warrant under Section 3 of the Obscene Publications Act and proceeded to confiscate about 2,000 copies of the last six issues along with all materials pertaining to small ads. In short, they are avoiding the major confrontation with IT’s editorial content; but their intentions are the same as they were two years ago – to put IT out of business.

Dear Friend,

Just a little over two years ago, Scotland Yard’s finest raided the offices of International Times, in an attempt to cripple the newspaper’s operation. This was part of a vast police scheme, which also involved actions against Last Exit to Brooklyn, against Robert Fraser’s Gallery, and many others.

The IT bust was the climax of this series of police manipulations, and subsequently sparked off a wave of public protest, including anti-censorship committees formed by people like Michael Kustow and John Calder.

[…]

This letter is to let you know that sinister operations have begun again, so undercover in fact, that most of you reading this are probably unaware of what is happening.

[…]

Just last week, the second of Scotland Yard’s raids on IT offices occurred. Seven ‘polite’ members of the squad entered the premises on Endell St. with yet another warrant under Section 3 of the Obscene Publications Act and proceeded to confiscate about 2,000 copies of the last six issues along with all materials pertaining to small ads. In short, they are avoiding the major confrontation with IT’s editorial content; but their intentions are the same as they were two years ago – to put IT out of business.

Circular from the International Times, in response to the 1969 raid, opening ‘dear friend’ and signed ‘peace and love’. Catalogue reference: DPP 2/4670.

Most concerning were the files and sealed letters that were seized relating to the small advert pages. These were records of gay and bisexual men who used these advertising pages and were hoping to find a safe space to explore partnerships and friendships. The front page of the next copy of IT reported on the raid, warning:

to those who have advertised with us in the last three months or have answered ads: since the police now have our files, be prepared for a surprise visit from them.

International Times, No. 56, 9-22 May 1969.

This time the case went to court. Those seen to be facilitating the publication and small adverts pages were put on trial: the paper's directors David Hall, Peter Stansill and Graham Keen.

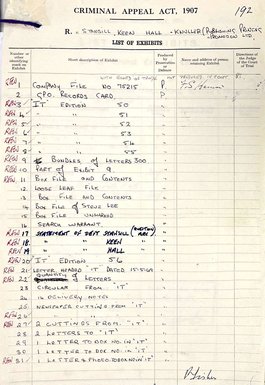

List of exhibits used as evidence in the case against David Hall, Peter Stansill, Graham Keen and Knuller Publishing, Printing and Promotions. Catalogue reference: CRIM 1/5306/1

Community language and identity

IT’s directors were accused of committing the old common law offences of conspiracy to outrage public decency and corrupting public morals. These charges were laid, despite the fact that the magazine took a robust approach to ‘policing’ its small adverts section. It routinely rejected those which detailed ‘perversions’, or which specified race – describing these as ‘archaic and not appropriate’.

The prosecution argued that though same-sex acts between men were legal in certain circumstances, promoting them publicly might nevertheless corrupt public morals or outrage public decency. This was heightened by concerns about the ages of both those posting and replying to adverts, who might not necessarily be of age to consent to same-sex acts. Prosecutors referenced several past cases, including one concerning a booklet selling sex worker services from 1959, and another from 1927 concerning men meeting other men in a private home.

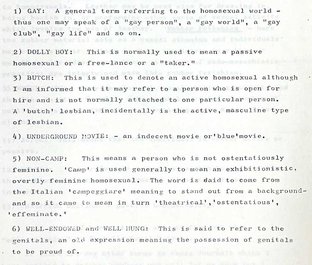

The authorities sought professional opinion on the language used in the adverts, focusing on the terminology and the frequency of it. Lists of definitions were drawn up to help the police understand the adverts.

Transcript

- GAY: A general term referring to the homosexual world – thus one may speak of a “gay person”, a “gay world”, a “gay club”, “gay life” and so on.

- DOLLY BOY: This is normally used to mean a passive homosexual or a free-lance or a “taker”.

- BUTCH: This is used to denote an active homosexual although I am informed that it may refer to a person who is open for hire and is not normally attached to one particular person. A ‘butch’ lesbian, incidentally is the active, masculine type of lesbian.

- UNDERGROUND MOVIE: - an indecent movie or ‘blue’ movie.

- NON-CAMP: This means a person who is not ostentatiously feminine. ‘Camp’ is used generally to mean an exhibitionistic, overtly feminine homosexual. The word is said to come from the Italian ‘campeggiare’ meaning to stand out from a background and so it came to mean in turn ‘theatrical’, ‘ostentatious’, ‘effeminate.’

- WELL-ENDOWED and WELL HUNG: This is said to refer to the genitals, an old expression meaning the possession of genitals to be proud of.

- GAY: A general term referring to the homosexual world – thus one may speak of a “gay person”, a “gay world”, a “gay club”, “gay life” and so on.

- DOLLY BOY: This is normally used to mean a passive homosexual or a free-lance or a “taker”.

- BUTCH: This is used to denote an active homosexual although I am informed that it may refer to a person who is open for hire and is not normally attached to one particular person. A ‘butch’ lesbian, incidentally is the active, masculine type of lesbian.

- UNDERGROUND MOVIE: - an indecent movie or ‘blue’ movie.

- NON-CAMP: This means a person who is not ostentatiously feminine. ‘Camp’ is used generally to mean an exhibitionistic, overtly feminine homosexual. The word is said to come from the Italian ‘campeggiare’ meaning to stand out from a background and so it came to mean in turn ‘theatrical’, ‘ostentatious’, ‘effeminate.’

- WELL-ENDOWED and WELL HUNG: This is said to refer to the genitals, an old expression meaning the possession of genitals to be proud of.

Terms defined by a Consultant Physician to support the police to understand the phrases being used in the classified adverts. Catalogue reference: DPP 2/4670.

On trial

Controversially, the raided records were used to track down some of the men who had placed classified adverts, requiring them to fill in questionnaires, make statements or testify in court. Legal guidance was sought and specified that these individuals would be immune from prosecution, but lawyers often advised their clients to remain silent.

The court assigned a letter to each individual to keep their anonymity at the trial. Personal advert writers were asked to declare their sexuality, explain the meaning of their advertisements and to share any replies they had received – most claimed to not have kept these. They also had to provide their age.

The LGBTQ+ rights campaigner Antony Grey commented, ‘Are such tactics – while possibly within the letter of the law – really in accordance with its spirit?’

Behind the scenes, the National Council for Civil Liberties (now known as Liberty) and specialist counselling organisation the Albany Trust were working to protect these men, recommending lawyers and gaining pockets of support in parliament. Meetings were held and open letters published, objecting to the ‘belief that homosexuals "corrupt" one another’ and the double standard, that explicit heterosexual adverts were not being policed (HCA/NCCL/3/11, LSE Special Collections).

A specialist from the Maudsley Hospital testified that the advertisements were not harmful in general for young people and could even bring happiness to those exploring their sexuality (catalogue reference: DPP 2/4669). The defence argued these adverts were a private interaction between the reader and publication. But the prosecution cited the high sales figures and extensive reach of the publication.

The IT and its printers lost at first instance, and the court of appeal dismissed their appeal. Judgments from similar cases, including Oz magazine, were carefully examined. The House of Lords, the highest court of appeal, upheld one count and dismissed the other. They felt themselves to be bound by the existing law, and under an obligation to enforce it, even if they disagreed with it. The Attorney-General Sir Peter Rawlinson commented, constitutionally: ‘It is for Parliament to change the law. It is for the prosecuting authorities to enforce the law.’

The outcome of the trial and appeals was mixed for those involved. The conviction for corrupting public morals stood, as did the suspended sentences imposed upon the defendants. On the other hand, a revised order for costs reduced the amount of court costs they had to pay. Ultimately, however, the magazine was forced to close.

Legacy

The policing of gay personal adverts, and the actions of the authorities in the IT case, created a climate of fear and stigma. Almost a decade later, the Southwark and Lambeth Campaign for Homosexual Equality complained that heterosexuals could advertise for partners freely, but publishers of similar advertisements for homosexuals were liable to prosecution.

Despite this, community resistance continued, LGBTQ+ rights groups increased, and queer culture thrived. Our classified advert records from the 1920s and 1960s demonstrate that people have always found ways to connect and support each other, regardless of societal constraints and the law. Through shared language and the creation of safe spaces, whether in written or physical forms, LGBTQ+ people continue to create their own means of connection.

A relaunch of the International Times lives on, and their online archive continues to provide access to old editions. LSE Library and Bishopsgate Institute house wonderful collections showing the importance of classified adverts from the 1960s onwards.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Director of Public Prosecutions papers relating to the International Times case

- Date

- 1966-1969

-

- Title

- Director of Public Prosecutions papers relating to the International Times case

- Date

- 1969-1971

-

- Title

- Law Officers' Department files

- Date

- 1970

Further reading

- Speaking out : writings on sex, law, politics, and society 1954-1995 by Antony Grey

- There's a riot going on : revolutionaries, rock stars and the rise and fall of '60s counter-culture by Peter Doggett.

- Gay men and the left in post-war Britain : how the personal got political by Lucy Robinson

- Conspiracy to corrupt public morals and the ‘unlawful’ status of homosexuality in Britain after 1967 by Harry Cocks (accessed 13 January 2025).