Record revealed

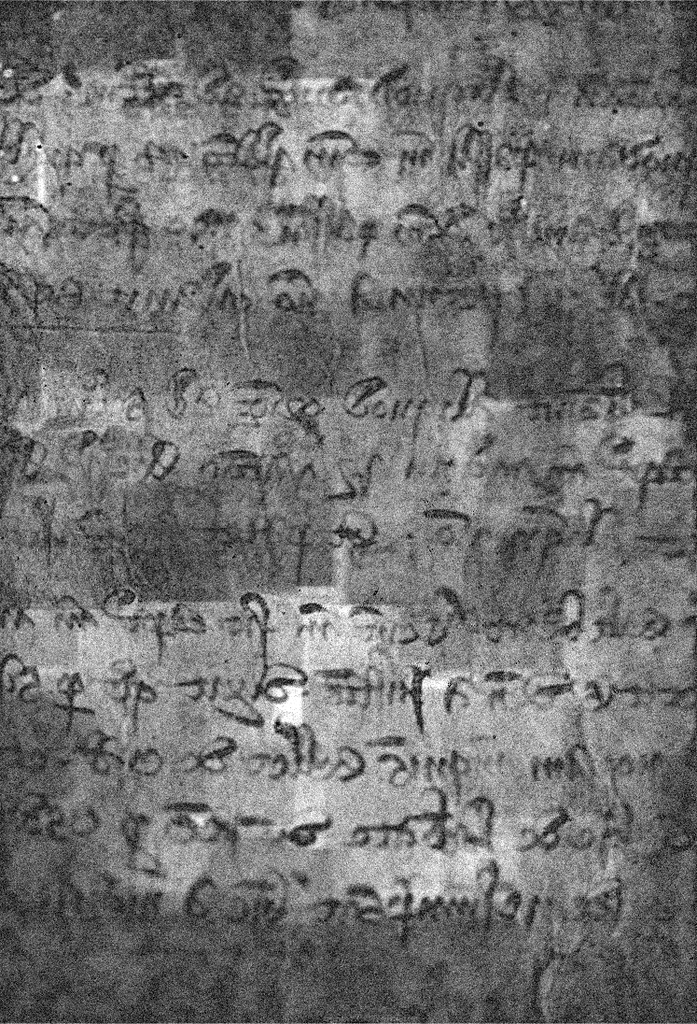

A medieval Irish roll with hidden grievances

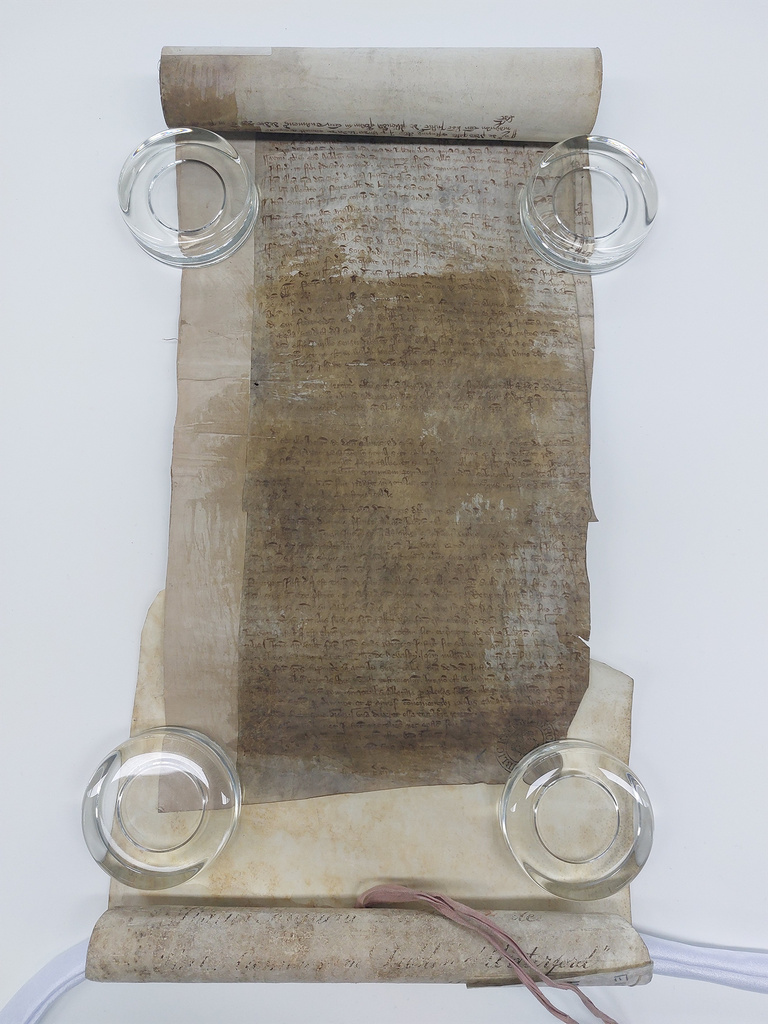

This unassuming roll provides a glimpse into how medieval Ireland was governed towards the end of the 13th century. Today, it plays a starring role in the development of scientific techniques that make apparently lost text, readable.

Image 1 of 3

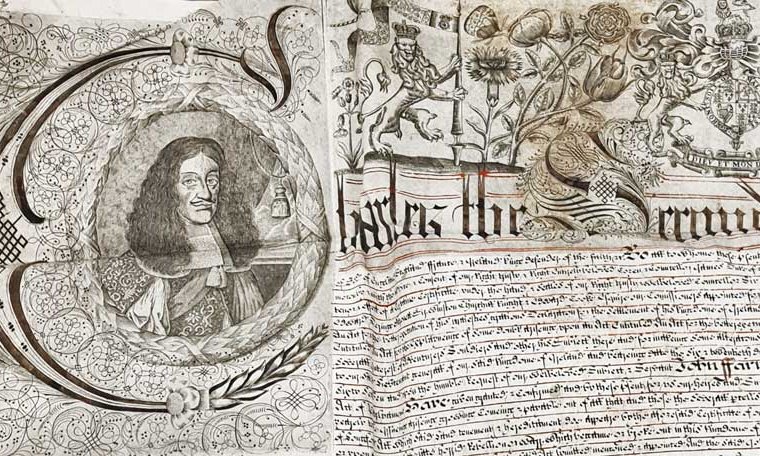

A medieval roll detailing the major offices in late 13th-century Ireland. Much of the text is illegible. Transcription and translation taken from, Elizabeth Biggs and Paul Dryburgh, ‘Report into the State of the Irish Exchequer, c. 1284’, Analecta Hibernica 53 (2023 ), 63-99, at pp. 80-3.

Transcript

25. Recipit justiciarius qui est thesaurarius pecuniam | <…> in patria in castris et cameris retinendo eam in garda sua dicit clerico suo quod ipsum | <…> receptas in rotulis suis et faciat tallias et sic factum est camerario denarios non vidente.

26. Similiter | liberavit justiciarius qui est thesaurarius pecuniam fere totam sic et precipit quod tales liberationes minime intrantur in ro | tulis.

27. Item quando vult facere litteras suas patentes justiciario sic solvente, quando vult tallias de scaccario que | <…> aliis tallias ut patet in abbate de Dewisky qui quamvis nullum warantum facit sic solventibus.

28. [Item] | quando facit ipsos inpingere in rotulis suis tali tantum de denariis justiciarii hic non est ordo hic non | <…> est [?etiam] aliqua veritas hic non est testimonium hic non est warantum. Debuerit sine moram | <…> facere poni in rotulis allocari per plenas solutiones vel per tales allocationes comp[utare] fieri | <…> et scribi per terminos et per annos convenientibus rotulis camerarii et rotulis thesaurarii et | <…> sine brevibus.

29. Una deberet esse totius terre recepta et nullas alias fieri nisi <…> | <…> et hoc nullus nec justiciarius nec thesaurarius nec operationes sine brevi. Et quia ali <…> | <…> ad dominum thesaurium qui totum <…>. Dominus justiciarius <…> | <…> modo et <…> fuit tempore suo qui ad <…> al <…>.

Translation

25. The justiciar who is treasurer receives the [king’s] money in the country, in castles and chambers to be retained in his custody, and he says to his clerk that, having [recorded] receipts in his rolls, he is to strike tallies, and this is done without the chamberlain viewing the money.

26. Similarly, the justiciar who is treasurer pays in money almost entirely in this manner, and he orders that such payments are scarcely entered in the rolls.

27. Whenever anyone wishes to have letters patent drawn up, he thus pays the justiciar, when he wants tallies from the exchequer, when he wants [any] other thing <…> as can be seen in the case of the abbot of Duiske, where he made no warrant for these payments.

28. However, whenever he causes to be intruded into his rolls so much of the justiciar’s money, this is not in order, this [is] not in any way the truth, this is not witness and this is not warrant. He ought without delay <…> [but] cause [it] to be placed on the rolls, to be allowed through full payments or through such allowances by which an account might be made <…> and cause rolls of the chamberlain and rolls of the treasurer to be compiled by terms and by years <…> without writs.

29. One ought to be received throughout the whole of the land and no others ought to be drawn up unless <…> and this neither the justiciar nor by the treasurer nor works without a writ. And because the lord treasurer who <…> the whole, the lord justiciar <…> now and <...> was in his time who...

Image 2 of 3

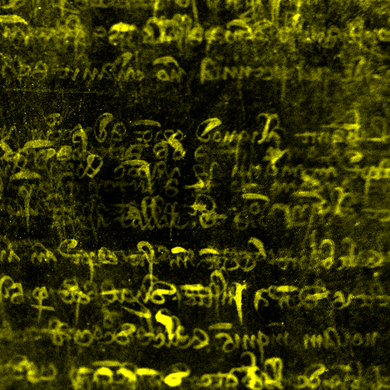

XRF analysis detecting iron, showing writing on the front and back of the roll overlapping.

Image 3 of 3

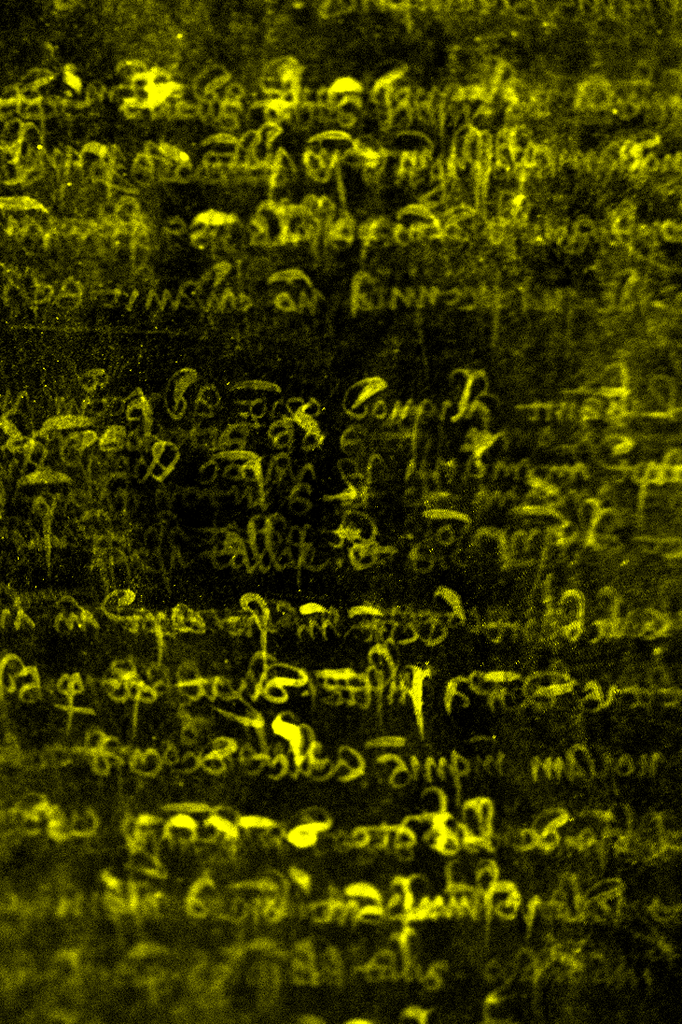

Through analysing different elements in isolation using XRF, it's possible to separate the writing on either side, making the text readable again.

Why this record matters

Date: 1284

Written in Latin, this roll describes the major governmental offices and the misbehaviours of senior officials in late 13th-century Ireland. The most detailed and damning of these relates to the operation of the Irish exchequer, responsible for collecting and spending the King’s money in Ireland. Accusations include bad custody resulting in the destruction of a copy of Ireland’s Domesday Book, and corrupt offers of money in exchange for offices in the exchequer.

The charges provide a glimpse into grievances of the local community and the power of these complaints to trigger inquiries. The roll is a snapshot of the exchequer before reforms were implemented, from 1293, following multiple corruption scandals.

This document stands as testament to the effects of conquest, collaboration and co-existence between England and Ireland over nearly four centuries from the 1170s. It's one of tens of thousands from this period at The National Archives and it forms part of the Virtual Treasury of Ireland, where the roll is also catalogued.

The dark staining covering the bottom half of the face of the first membrane is not original or contemporary, but the result of galling. This practice, most common in the 19th century, was the brushing of gallic or tannic acid onto documents to improve the readability of faded text. However, galling was only a temporary solution, sometimes only lasting a few hours. Over time, the acid has darkened, reducing the readability of the treated area even further. The person likely responsible for the galling is 19th-century medievalist Henry Savage Sweetman, who produced a partial transcription in 1879. For years, Sweetman’s work was one of the principal means of accessing the history of medieval colony of Ireland.

Today, working with imaging scientists at University College London, heritage scientists at Historic Royal Palaces, and imaging specialists at Clyde HSI, our heritage scientists have produced high resolution images of the roll – including X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS). Record specialists can now fully transcribe the document. This includes previously damaged words, illegible even to Sweetman, such as a description of the tallies being mishandled by the abbot of Duiske in county Kilkenny.

This small roll has a significant place within the development of these new, non-invasive methodologies that have the potential to impact the study of pre-modern history. With them, we can see behind the gall, accessing previously unreadable text for the first time in hundreds of years.