An historic role

When the iconic Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury in June 1948, the Caribbean passengers onboard were welcomed by a Colonial Office representative – Ivor Gustavus Cummings.

First of all let me welcome you to Great Britain and express the hope that you will all achieve the objects which have brought you here.

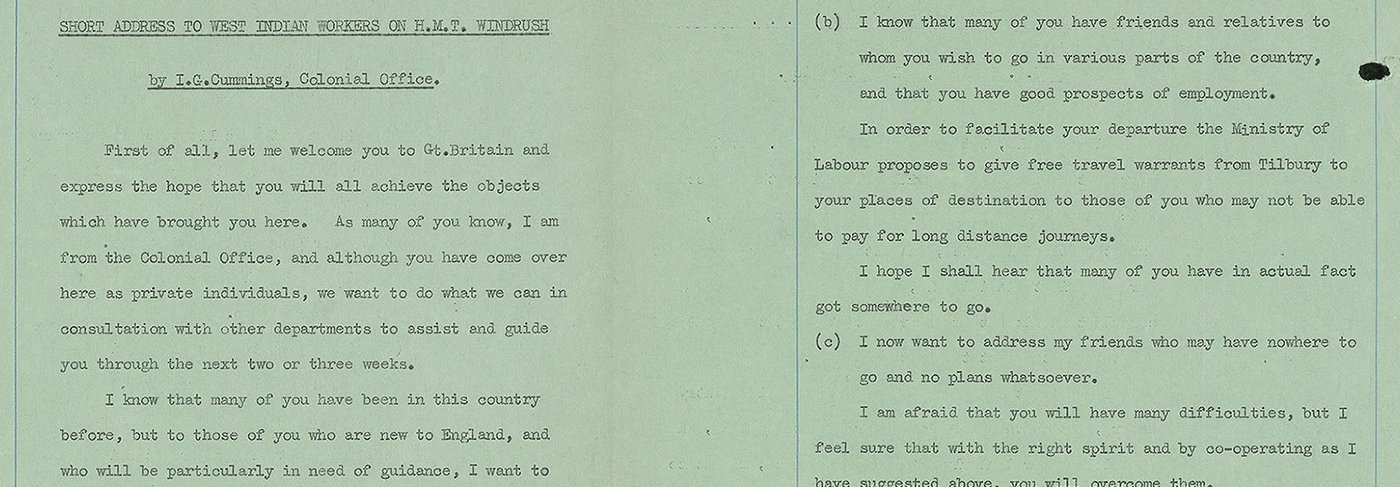

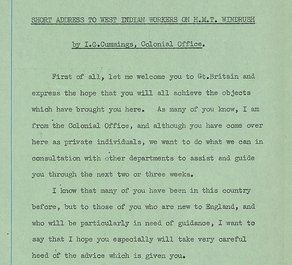

Short address to West Indian Workers on HMT Windrush. Catalogue reference: CO 876/88

Who was Ivor Cummings? Why was he tasked with this important role? And why did he later become known, in the words of sociologist Nicholas Boston, as the ‘gay father of the Windrush generation’?

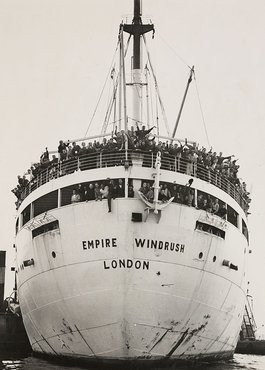

Passengers crowd the decks of HMT Empire Windrush as it docks at Tilbury in Essex. Image: Daily Herald Archive via Getty Images

Early life

Ivor Gustavus Cummings was born in approximately 1913 in West Hartlepool. His father, Ismael Cummings, was a doctor who had been born in Sierra Leone. His mother was Johanna Archer, a white English nurse. Ismael was listed as a medical student in the 1911 census, and just two years later he met Johanna when they worked together at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle. Ivor was born shortly afterwards.

At a young age Ivor and his mother moved to Surrey, while his father returned to Sierra Leone. Ivor and Johanna associated with the widow and children of famed composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, who also had Sierra Leonian heritage.

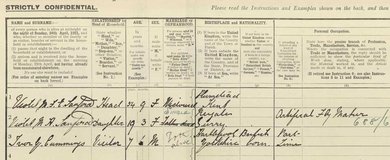

In the 1921 census Ivor is listed as visiting Violet Sanford, widow, and her daughter. It is unclear why he was staying here, although it was near his family home in Croydon.

Census schedule for Ivor G Cummings, 1921. Catalogue reference: RG 15/3399

Ivor was privately educated, facing discrimination based on his background. He went to Sierra Leone but also struggled to fit in at school there. He finally flourished at Dulwich College in South London, where his academic talents were nurtured. This had a significant impact on his later life.

Student support at Aggrey House

In the 1930s Ivor worked as the warden of Aggrey House, Bloomsbury, a hostel set up for African students and people of African descent in Britain. Such hostels were opened to accommodate students from Africa and the Caribbean who might otherwise have had to face a harsh reality – being barred from renting rooms. The hostels proved very successful, providing practical support and creating a sense of community.

Ivor took on the role aged 22, in 1935, just a year after Aggrey House had opened. Unlike other similar hostels, Aggrey house was connected to the Colonial Office. This caused some controversy – it was perceived with distrust by anti-colonial students and activists. The prominent campaigning organisation the League of Coloured Peoples (LCP) were also instrumental in its creation.

In his role as warden Ivor looked after student welfare, including organising social events, from tennis tournaments and whist drives to dances and lectures. He was clearly politically engaged, with speakers at Aggrey House covering themes such as ‘Present day slavery and the problem of its abolition’ by Anglo-Irish anti-slavery activist Lady Simon, and hosting esteemed pan-Africanists such as George Padmore.

Despite the controversy connected to Aggrey House, this was one of many instances that showed Ivor’s interest in the welfare of Black individuals.

Sexuality

Ivor was gay and socialised in Black queer intellectual circles in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1939, he was listed as single on the 1939 Register, living at Aggrey House. This was an era where it was difficult to be open about being gay, as sex acts between men were criminalised. This was likely to have been especially hard to navigate as a Black man in the interwar and post war period.

We don’t know the language Ivor would have used to self-define. Despite this, Ivor seemingly didn’t hide his sexuality in the way he presented, and was described by Mike and Trevor Phillips as ‘a fastidious, elegant man, with a manner reminiscent of Noel Coward’.

Despite criminalisation, there was a significant underground gay community in interwar London. Individuals frequented private members clubs and other spaces. Particularly popular with the Black community was the Shim Sham club, a venue that championed jazz music from across the Atlantic. Though we don’t have evidence that Ivor visited such places, it’s entirely possible, as some of his acquaintances were known to.

One of Ivor’s closest friends was the gay Guyanese dancer and bandleader Ken Johnson, a leading figure in Black British music in the 1930s. When Ken died, Ivor led on the memorial arrangements through his position of influence at the Colonial Office.

Advocate and ally at the Colonial Welfare Office

Ivor had personal experiences of racism, from his schooling days and beyond. In later life he spoke about how he had tried to gain a commission at the outbreak of the Second World War, but was prevented by his ancestry. The stipulations were to be of ‘pure European decent’, as Stephen Bourne notes. This was later overturned but by then he had joined the Colonial Office.

Ivor became the first Black person to obtain a position in the Office in 1941. He worked with the Colonial Welfare Office, and was to become Secretary to the Advisory Committee on the Welfare of Colonial People in the United Kingdom.

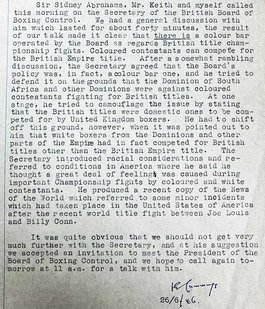

Ivor continued to advocate for Black Britons through these roles, fighting the colour bar in boxing and meeting African and Caribbean merchant seamen to discuss the daily barriers they faced. His attitude to such advocacy is noted in a colleagues’ comments about the colour bar at the British Boxing Board of Control:

I think the best person who could deal with this matter and relish the fight would be Mr. Cummings (a very keen fan of boxing and, I am told, no means amateur)...

Letter regarding the colour bar in British boxing, 1947. Catalogue reference: CO 876/89

Partial transcript

Sir Sidney Abrahams, Mr. Keith and myself called this morning on the Secretary of the British Board of Boxing Control. We had a general discussion with him which lasted for about forty minutes, the result of our talk made it clear that there is a colour bar operated by the Board as regards British title championship fights. Coloured contestants can compete for the British Empire title. After a somewhat rambling discussion, the Secretary agreed that the Board’s policy was, in fact, a colour bar one, and he tried to defend it on the grounds that the Dominion of South Africa and other Dominions were against coloured contestants fighting for British titles. At one stage, he tried to camouflage the issue by stating that the British titles were domestic ones to be competed for by United Kingdom boxers. He had to shift off this ground, however, when it was pointed out to him that white boxers from the Dominions and other parts of the Empire had in fact competed for British titles other than the British Empire title. The Secretary introduced racial considerations and referred to conditions in America where he said he thought a great deal of feeling was caused during important Championship fights by coloured and white contestants.

[…]

It was quite obvious that we should not get very much further with the Secretary, and at his suggestion we accepted an invitation to meet the President of the Board of Boxing Control, and we hope to call again tomorrow at 11a.m. for a talk with him.

Sir Sidney Abrahams, Mr. Keith and myself called this morning on the Secretary of the British Board of Boxing Control. We had a general discussion with him which lasted for about forty minutes, the result of our talk made it clear that there is a colour bar operated by the Board as regards British title championship fights. Coloured contestants can compete for the British Empire title. After a somewhat rambling discussion, the Secretary agreed that the Board’s policy was, in fact, a colour bar one, and he tried to defend it on the grounds that the Dominion of South Africa and other Dominions were against coloured contestants fighting for British titles. At one stage, he tried to camouflage the issue by stating that the British titles were domestic ones to be competed for by United Kingdom boxers. He had to shift off this ground, however, when it was pointed out to him that white boxers from the Dominions and other parts of the Empire had in fact competed for British titles other than the British Empire title. The Secretary introduced racial considerations and referred to conditions in America where he said he thought a great deal of feeling was caused during important Championship fights by coloured and white contestants.

[…]

It was quite obvious that we should not get very much further with the Secretary, and at his suggestion we accepted an invitation to meet the President of the Board of Boxing Control, and we hope to call again tomorrow at 11a.m. for a talk with him.

Colonial Office note by Ivor Cummings about the colour bar in British boxing, 1946. Catalogue reference: CO 876/89

In 1942, the League of Coloured Peoples commended the increasingly important and visible roles being taken up by Black individuals such as Ivor and Learie Constantine. These individuals also received backlash for supporting government institutions which were perceived by many to be upholding systems of oppression at home and across the Colonies. Did Ivor feel conflicted working inside an institution that had this reputation?

The Empire Windrush

In early June 1948, Ivor received an OBE for his Colonial Office work. At this time, very few people of colour were recognised with this title.

It was just following this that Ivor was sent to meet the Caribbean passengers travelling on the Empire Windrush. He worked in the department tasked with organising many aspects of these passengers’ arrival – including transport from Tilbury and the temporary accommodation at Clapham Shelter for those without proposed addresses.

As Ivor wrote in Colonial Office correspondence, ‘it is most important politically… that they are received and accommodated upon arrival’. He was briefing significant figures in government, including the Prime Minister.

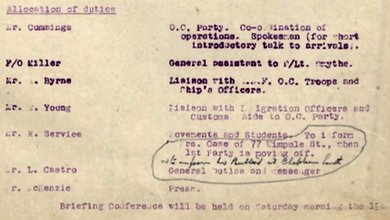

Official document describing Mr Cummings as coordinator of operations and spokesperson. Catalogue reference: CO 876/88

At Tilbury, Ivor was the government coordinator, as well as spokesperson. Documents note that the Windrush docked late on the night of 21 June and Ivor delivered his words by the ship’s broadcast system. Representatives from the Colonial Office, Ministry of Labour and the RAF were there to support arrivals finding work and accommodation. By this point the passengers had had a long journey of several weeks and must have been desperate to disembark.

Why was Ivor chosen to deliver this address? Perhaps it was a tactical approach by the Colonial Office – a way of trying to present the so called ‘mother country’ in a certain, appealing light. The government was keen to try and placate the increased anti-colonial agitation that had followed the war, by appearing as anti-discriminatory as possible.

Transcript

SHORT ADDRESS TO WEST INDIAN WORKERS ON H.M.T WINDRUSH

By I.G.Cummings, Colonial Office.

First of all, let me welcome you to Gt. Britain and express the hope that you will all achieve the objects which have brought you here. As many of you know, I am from the Colonial Office, and although you have come over here as private individuals, we want to do what we can in consultation with other departments to assist and guide you through the next two or three weeks.

I know that many of you have been in this country before, but to those of you who are new to England, and who will be particularly in need of guidance, I want to say that I hope you especially will take very careful heed of the advice which is given to you.

SHORT ADDRESS TO WEST INDIAN WORKERS ON H.M.T WINDRUSH

By I.G.Cummings, Colonial Office.

First of all, let me welcome you to Gt. Britain and express the hope that you will all achieve the objects which have brought you here. As many of you know, I am from the Colonial Office, and although you have come over here as private individuals, we want to do what we can in consultation with other departments to assist and guide you through the next two or three weeks.

I know that many of you have been in this country before, but to those of you who are new to England, and who will be particularly in need of guidance, I want to say that I hope you especially will take very careful heed of the advice which is given to you.

An extract from Short address to West Indian Workers on HMT Windrush. Catalogue reference: CO 876/88

Ivor’s short speech was welcoming but factual. As he acknowledged, for many passengers this was not their first time in Britain. His address to the passengers closed with the words: ‘I wish you the very best of luck.’

Ivor knew only too well – from his work and personal experiences – the barriers these individuals were likely to face.

Windrush legacy

A letter from Henry Laurence Lindo, a prominent Jamaican, conveyed his thanks to Ivor in helping these arrivals: ‘As a Jamaican and one officially concerned with these matters, I am myself very grateful’.

In his following reports, Ivor described the passengers as a ‘mixed bunch’ that were more employable than had been hoped. Ivor continued correspondence regionally, attempting to support these men in finding work in places from Bolton to Warwickshire. He was also involved in supporting workers on later ships from the Caribbean, including the SS Orbita.

In the decades that followed, Ivor’s interest in student welfare continued – he co-authored a report on the experiences of colonial students in the USA. By 1958 he had resigned his position at the Colonial Office, and worked for the government in Ghana.

Ivor’s name pops up regularly across government departments from the 1930s onwards. The perspective we hold is that of government, which tells a lot about his working life but little about his thoughts and feelings of working within a government institution – his anti-racist work, and his daily life as a queer Black Briton. As historian Gemma Romain notes, his ‘life story is yet to be fully explored’, and it deserves to be better known.

In a time of racial tensions and hostility, Ivor Cummings was an important advocate for the rights of Black people, in Britain and abroad, and hopefully made those who were first time visitors to Britain on the Empire Windrush feel more welcome.

Further reading

Nicolas Boston, "Ivor Cummings was the ‘gay father of the Windrush generation’ – so why haven’t we heard of him?", independent.co.uk, 25 June 2019 (Accessed 19 June 2023).

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Census: South Croyden sub-district

- Date

- 1921

-

- Title

- 1939 Register

- Date

- 1939

-

- Title

- British boxing: Colour bar

- Date

- 1947

-

- Title

- Employment of Jamaicans from the S.S. EMPIRE WINDRUSH

- Date

- 1948