The queer Victorian origins of the word 'camp'

Did you know that the word ‘camp’ was used by members of the LGBTQ+ community as early as 1868? The word ‘campish’ can be found in a letter by theatre performer Fanny Boulton. We look at the origins of the word and how this early example ended up in government records held at The National Archives.

Important information

This article contains references to historical attempts to police sexuality, gender identity and gender presentation. The modern umbrella terms 'queer' and 'LGBTQ+' are used here to encompass a range of sexualities and gender expressions.

Subcultural origins

‘Camp’ – a word associated with theatricality, playfulness and exaggeration. It’s a term that can relate to aesthetics or the way someone acts and has long been connected to gay culture and communities.

The word ‘camp’ is thought to have French origins and the first dictionary definition is from 1909 in the Oxford English Dictionary. However, its use pre-dates this significantly. It was initially more likely to be spoken in and limited to more underground spaces and subcultures. Camp challenges social norms and hierarchies by intentionally being different and bold. But being different was not always a safe or encouraged thing to be.

One of the earliest known uses of ‘camp’ in what we would recognise as its current meaning was as part of a scandalous court case in 1871. The exact phrase was ‘my “campish” undertakings’, found in a letter from one half of the renowned 19th-century duo of theatrical performers Fanny and Stella.

Fanny and Stella

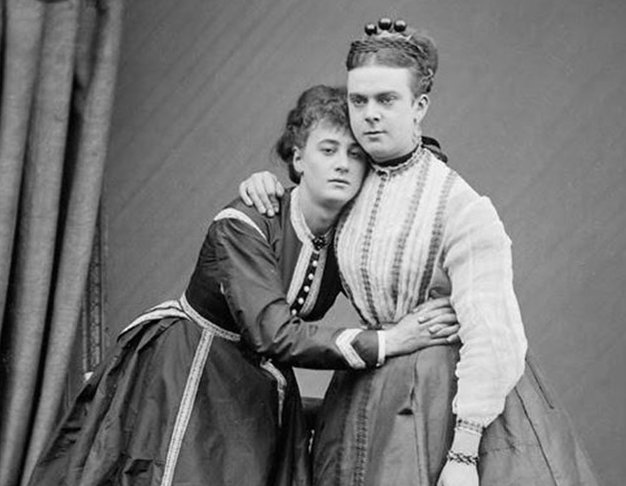

Fanny and Stella photographed around 1869, the year before their arrest. Photograph by Frederick Spalding. Restored. Essex Record Office D/F 269/1/3712, Public domain.

Fanny Park and Stella Boulton, who were both assigned as male at birth, presented as women on stage and off. Records held at The National Archives reveal that, among family and friends, they used masculine and feminine names and pronouns interchangeably. We have used here the names that they used in their own letters, in recognition of their gender presentation at the time.

Although the language was not available in their lifetime, given the chance they might have identified as trans, non-binary or gender fluid. They certainly lived their lives in ways that we would now recognise in these terms, and challenged socially accepted ideas of gender at the time.

In 1870, Fanny and Stella went for a night at the theatre with a couple of male friends. They attended in lavish dresses and were read by people around them as female.

However, they had unknowingly been under observation by undercover police for some time. The wearing of ‘female attire’ away from the protection of the theatre stage prompted scrutiny. Fanny, Stella and their friends were all arrested for ‘outraging public decency’.

The charge prompted debate at the time. While there was occasional use of the charge of ‘masquerading’ to control gender presentation in public spaces, wearing clothes different from those expected of your assigned gender was not explicitly criminalised.

They were also charged with the ‘abominable crime of buggery’ – this was a notoriously hard accusation to prove, often requiring witnesses to the act.

Arthur Clinton’s letters

At the time Stella was in a brief relationship with Lord Arthur Clinton, and they used the language of marriage to discuss their relationship. Arthur had been lodging with Ann Empson, who handed 2,000 letters over to the courts as evidence. Only a small number survive, and a few of these were from Fanny and Stella.

The National Archives hold the associated trial papers, including court transcripts of the letters, which give us an amazing insight into these individuals' lives. In these letters, Fanny signs her name Fanny Winifred Park and describes herself as Arthur’s sister-in-law. Another letter was signed off by Stella Clinton, taking Arthur’s last name.

In one letter to Arthur, Fanny writes:

My “campish” undertakings are not at present meeting with the success which they deserve, whatever I do seems to get me into hot water somewhere but that’s not important.

Transcript

16 John Street, Minories, London, Dec 4th 1868

My dearest Arthur,

I am just off to Chelmsford with Fanny where I shall stay till Moday. We are going to a party there tomorrow night. Send me some money Wretch.

Stella Clinton.

Duke Street

Nov 21st

My dearest Arthur,

How very kind of you to think of me on my birthday. I had no idea that you would do so. It was very good of you to write and I am really very grateful to you for it. I require no remembrance of my Sisters husband as the many kindnesses he has bestowed upon me will make me remember him for many a year and the Birthday present he is so kind as to promise me will be only one addition to the heap of little favours I already treasure up. So many thanks for it dear old man. I cannot echo your wish that I should live to be a hundred though I should like to live to a green old age – green! Did I say oh ciel the amount of paint that will be required to hide that very unbecoming tint. My “campish” undertakings are not at present meeting with the success which they deserve, whatever I do seems to get me into hot water somewhere but n’importer whats the odds as long as youre rappy.

Once more with many many thanks

Believe me

Your affectionate sister in law

(signed) Fanny Winifred Park.

16 John Street, Minories, London, Dec 4th 1868

My dearest Arthur,

I am just off to Chelmsford with Fanny where I shall stay till Moday. We are going to a party there tomorrow night. Send me some money Wretch.

Stella Clinton.

Duke Street

Nov 21st

My dearest Arthur,

How very kind of you to think of me on my birthday. I had no idea that you would do so. It was very good of you to write and I am really very grateful to you for it. I require no remembrance of my Sisters husband as the many kindnesses he has bestowed upon me will make me remember him for many a year and the Birthday present he is so kind as to promise me will be only one addition to the heap of little favours I already treasure up. So many thanks for it dear old man. I cannot echo your wish that I should live to be a hundred though I should like to live to a green old age – green! Did I say oh ciel the amount of paint that will be required to hide that very unbecoming tint. My “campish” undertakings are not at present meeting with the success which they deserve, whatever I do seems to get me into hot water somewhere but n’importer whats the odds as long as youre rappy.

Once more with many many thanks

Believe me

Your affectionate sister in law

(signed) Fanny Winifred Park.

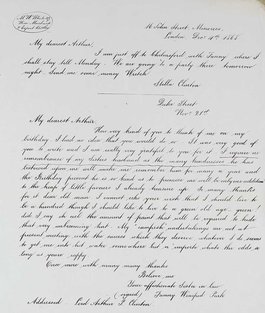

Trial transcripts of two letters from 1868 from Fanny and Stella to Arthur Clinton including the phrase ‘my ”campish” undertakings’. Catalogue reference: KB 6/3.

The implication is that these ‘”campish” undertakings’ refer to Stella’s presentation and way of living, including dress, demeanour and make up. The use of quote marks around the word 'campish' seems to acknowledge this was not an established word but more of a subcultural expression. The references to 'not meeting with the success they deserve' and being in 'hot-water' suggest backlash to Stella’s camp appearance.

The trial

On 9 May 1871, the trial began and various witnesses took to the stand over several days. For their initial court appearance Fanny and Stella had both worn dresses, but this time they presented as masculine, presumably an intentional decision as part of their defence.

The press described the moment these records were read out in court. The accused ‘hung down their heads during the reading of letters, and often smiled at the most ludicrous parts.’ Discussions in the courtroom hinged on whether these were letters of love or friendship.

Several of the letters also use the word ‘drag’ – the wearing of clothes perceived to be of a different gender, often exaggerated and for performance. The first recorded use of the word in relation to queerness was in reference to this case. Both 'campish' and 'drag' were printed in the press. This spectacle around the policing of gender actually created mainstream visibility of queer communities and awareness of this coded language.

After a six-day trial, a jury found Fanny and Stella and their accomplices at the theatre not guilty of the key charges and they were acquitted. Their use of drag in their performances ended up protecting them offstage – it was seen as an extension of their theatrical roles. The court’s frustration at the lack of ability to charge for ‘buggery’, which could not be proved, is believed to have influenced the broadening of the law to criminalise a wider range of acts relating to homosexuality.

Fanny and Stella continued to perform on stage after this time, but not as the iconic duo they once had been.

The pair strove to live their lives authentically, in 'campish' ways that boldly challenged gender norms of the time. It seems appropriate they are an important part of the recorded history of the word 'camp'.

Blog: Fanny and Stella: Piecing together LGBTQ+ histories and telling the stories

In 2021 to mark the 150th anniversary of the trial, Dr Mollie Clarke looked at the story of Fanny and Stella, and the importance of archival materials in understanding LGBTQ+ history.