The path to recruitment

Anthony Blunt (1907–1983) was the son of a vicar, and was born and privately educated in the South West of England. He won a scholarship to attend Trinity College, Cambridge in 1926, and two years later was elected to the Cambridge Apostles, a secret discussion group of disaffected, clever young men.

While teaching at Cambridge in 1931, he met Guy Burgess, who was a brilliant student and highly gregarious. Blunt became fascinated by the young man’s lively mind and thought-provoking conversation.

Trinity College, Cambridge, where Blunt studied and then taught. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Burgess developed an interest in Marxism, and around the year 1933, as he became aware of the danger posed by fascism, Blunt began to sympathise with communist ideas too.

The exact manner and date by which Blunt became a Soviet agent is unclear, but it is understood that he was recruited in early 1937 – not long after Burgess. They and three others (Kim Philby, Donald Maclean and John Cairncross) would go on to become known as the Cambridge Five: a group of Cambridge University graduates who were revealed to have shared classified information with the Soviet Union.

Though they were connected and sometimes conspired together, the Five operated with a measure of independence from one another – offering some security if any of them were to be caught.

Intelligence work and beyond

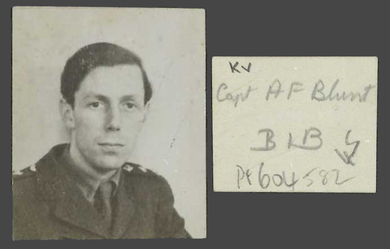

When the Second World War broke out, Blunt joined the British Army and served in France in the Intelligence Corps. The Security Service (MI5) recruited him in 1940, giving him access to secret information, which he passed on to his Soviet handlers.

Undated photo of a young Captain Anthony Blunt. Catalogue reference: KV 2/4700

By the end of the war Blunt wound up his work for MI5, and in 1945 he was appointed Surveyor of the King’s (and later the Queen’s) Pictures, responsible for the Royal Collection of Pictures. In addition, in 1947 he became Director of the Courtauld Institute, a highly significant centre of training and research in art history. For his work he was knighted in 1956.

Although Blunt’s active intelligence work was supposed to have ceased in 1945, he did maintain contact with Soviet agents. In 1951 he assisted Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean in their escape from Britain, with the pair reaching Moscow before MI5 could catch up with them.

MI5 embarked on an extensive investigation to identify any further NKGB (Soviet Intelligence) spies. This included many interviews with Blunt, but, although Security Service officers fretted about some discrepancies in his version of events, Blunt himself was not suspected of being a spy. That is, until Michael Straight came forward.

Allegations and interview

Michael Straight was an American magazine publisher and novelist who had been a student at Cambridge in the mid 1930s. In 1963 he decided to voluntarily tell the US authorities about his recruitment by Soviet Intelligence. This paved the way for MI5 Officer Arthur Martin to interview Straight on 26 February 1964, an account of which can be found at The National Archives in file KV 2/4705. Straight confirmed that Blunt had recruited him to the NKGB.

Martin then went on to interview Blunt in his flat above the Courtauld Institute on 23 April 1964, and he gave a riveting account of what happened. It reads as if it were a gripping novel.

Home House in 2023, where sixty years earlier, Arthur Martin had confronted Anthony Blunt above The Courtauld Institute. Image: Wikimedia Commons

On meeting Blunt, Martin said to him that he had been interviewed eleven times since 1951 and MI5 had assumed that he would be completely frank. 'Had this been a correct assumption?’ Blunt said that it had.

Martin followed this up: ‘I asked him again to say whether he had told us everything he knew and he looked me straight in the eye (rather too straight I thought) and said that he had’.

Martin then raised the stakes, telling Blunt that in America he had met Michael Straight. He passed Blunt a photograph of Straight, and asked him to tell all he knew about him. Blunt said he remembered him at Cambridge, that he was probably a member of the Communist Party for a time, but by the time Straight had left for America he had left the party. Martin noted a potentially revealing detail:

I noticed by this time BLUNT’s right cheek was twitching a good deal and I allowed a long pause before saying that Michael STRAIGHT’s account was rather different from his.

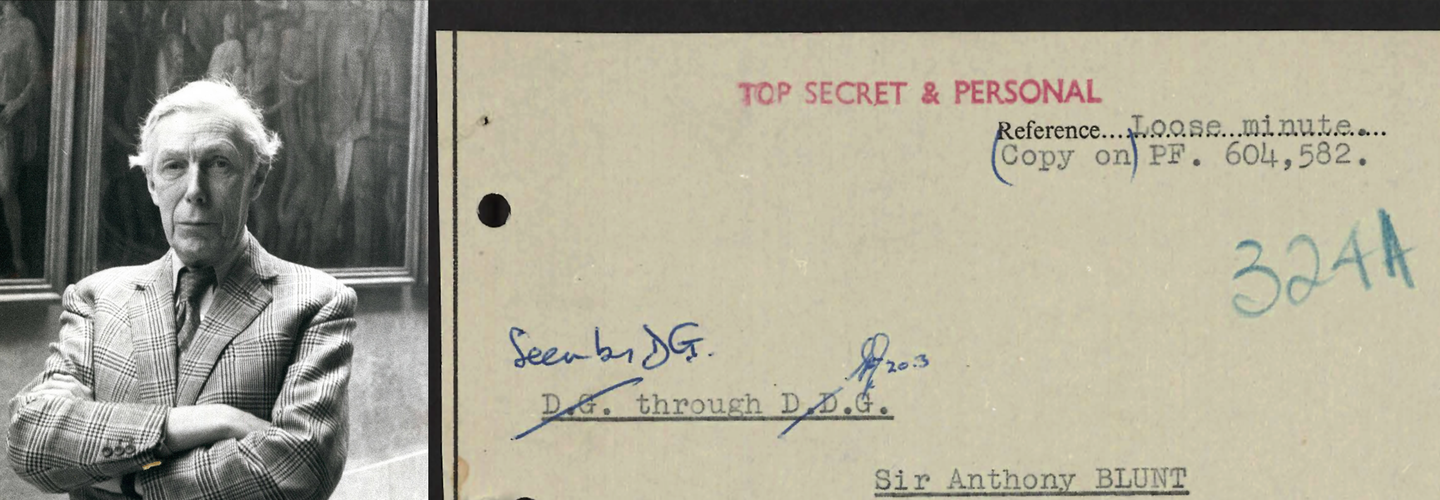

Anthony Martin's interview notes. Catalogue reference: KV 2/4705

Martin then went on to relate Straight’s account of how Blunt had recruited him to serve the Soviets in 1937. Blunt’s reaction was to dismiss the story as ‘pure fantasy’.

Unruffled, Martin mentioned that Straight had suggested that the three of them should meet – ie Straight wanted to meet Blunt with an MI5 officer present.

'The break'

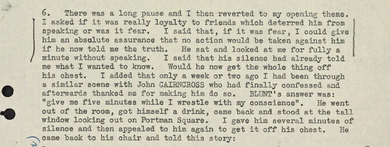

Martin paints a vivid picture of the scene when he finally broke through Blunt's resistance – and in it, he comes across as a skilful and persuasive interrogator:

Transcript

6. There was a long pause and I then reverted to my opening theme. I asked if it was really loyalty to friends which deterred him from speaking or was it fear. I said that, if it was fear, I could give him an absolute assurance that no action would be taken against him if he now told me the truth. He sat and looked at me for fully a minute without speaking. I said that his silence had already told me what I wanted to know. Would he now get the whole thing off his chest. I added that only a week or two ago I had been through a similar scene with John CAIRNCROSS who had finally confessed and afterwards thanked me for making him do so. BLUNT's answer was: "give me five minutes while I wrestle with my conscience". He went out of the room, got himself a drink, came back and stood at the tall window looking out on Portman Square. I gave him several minutes of silence and then appealed to him again to get it off his chest. He came back to his chair and told this story:

6. There was a long pause and I then reverted to my opening theme. I asked if it was really loyalty to friends which deterred him from speaking or was it fear. I said that, if it was fear, I could give him an absolute assurance that no action would be taken against him if he now told me the truth. He sat and looked at me for fully a minute without speaking. I said that his silence had already told me what I wanted to know. Would he now get the whole thing off his chest. I added that only a week or two ago I had been through a similar scene with John CAIRNCROSS who had finally confessed and afterwards thanked me for making him do so. BLUNT's answer was: "give me five minutes while I wrestle with my conscience". He went out of the room, got himself a drink, came back and stood at the tall window looking out on Portman Square. I gave him several minutes of silence and then appealed to him again to get it off his chest. He came back to his chair and told this story:

Blunt, about to embark on his confession, as described by Arthur Martin. Catalogue reference: KV 2/4705

Blunt revealed that it was Burgess who had introduced him to his first Russian controller who was called ‘George’, described as ‘a heavy, squat man who spoke English with a thick accent’. This was some time before June 1937, when Blunt left Cambridge.

There was an interruption in his contact with the Russians – after joining the Security Service in 1940, it was two or three months before Blunt was re-introduced to them. Then comes this damning statement: ‘from the time of his reintroduction to the Russians to the end of the war Blunt gave them all the information which came his way’.

Blunt went on to say that from 1946 to 1951 he had no meetings with the Russians, though he did remain in contact with Burgess. He played no part in arranging the flight of Burgess and Maclean, though he was ‘generally aware of what was going on’. His last meeting ever with a Russian contact , ‘Peter’, was in June or July 1951.

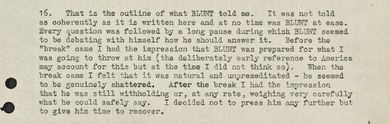

Interestingly, Martin comments that ‘at no time was Blunt at ease'. He notes that although 'the break' – i.e. the moment when Blunt began to talk about his espionage – felt 'natural and unpremeditated', he believed that Blunt was still holding back:

Transcript

16. That is the outline of what BLUNT told me. It was not told as coherently as it is written here and at no time was BLUNT at ease. Every question was followed by a long pause during which BLUNT seemed to be debating with himself how he should answer it. Before the "break" came I had the impression that BLUNT was prepared for what I was going to throw at him (the deliberately early reference to America may account for this but at the time I did not think so). When the break came I felt that it was natural and unpremeditated – he seemed to be genuinely shattered. After the break I had the impression that he was still withholding or, at any rate, weighting very carefully what he could safely say. I decided not to press him any further but to give him time to recover.

16. That is the outline of what BLUNT told me. It was not told as coherently as it is written here and at no time was BLUNT at ease. Every question was followed by a long pause during which BLUNT seemed to be debating with himself how he should answer it. Before the "break" came I had the impression that BLUNT was prepared for what I was going to throw at him (the deliberately early reference to America may account for this but at the time I did not think so). When the break came I felt that it was natural and unpremeditated – he seemed to be genuinely shattered. After the break I had the impression that he was still withholding or, at any rate, weighting very carefully what he could safely say. I decided not to press him any further but to give him time to recover.

Arthur Martin's impressions of Blunt during his confession. Catalogue reference: KV 2/4705

Blunt agreed to further interviews with Martin, and they parted on a surprisingly jovial note, ‘joking about the idea of a dinner a trois (i.e. with Michael Straight) which Blunt felt would be macabre’.

In fact the file shows that such a meeting did indeed take place, within a month, on 19 May 1964. Any tensions at that encounter were eased by alcohol, Martin finding that ‘the exchange of gossip became quite animated’.

Files at The National Archives contain further details about Blunt's various interviews. He never spoke in a wholly frank manner about his role either as a spy, or his assistance in supporting other members of the Cambridge Five.

Later twists and turns

Blunt kept his position as Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures until 1972, and remained in an advisory capacity to the Royal Collection until 1978. As such, he stayed at the heart of the establishment for over 30 years, having been given immunity from prosecution in return for confessing to espionage in 1964.

In 1979, journalist Andrew Boyle published Climate of Treason, a non-fiction book about the Cambridge spies. It referred to Burgess, Maclean and Philby by name, but also included a figure called ‘Maurice’, who was obviously modelled on Blunt.

Blunt was gay, and Boyle's choice to call him 'Maurice' was a reference to a well-known E.M. Forster novel about a gay man. In the wake of their defection in 1951, it became public knowledge that Guy Burgess was gay, and Donald Maclean was widely perceived to be gay or bisexual. This fostered a climate in the 1950s and 60s in which gay men in governmental posts were seen as outsiders and potential traitors. They were linked with Marxism and increasingly viewed as security risks at a time when male homosexuality was illegal in the UK.

When Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister in 1979, she wasn’t happy to discover that Blunt had been given immunity from prosecution in return for his confession. She felt that Blunt’s identity as a former spy should be put in the public domain, so she disclosed this in Parliament and Blunt, now publicly disgraced, was besieged by the press. Subsequently, his knighthood was removed.

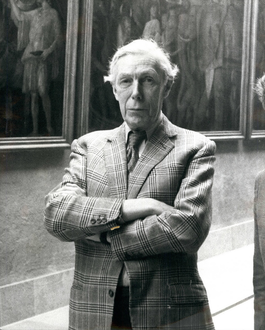

Anthony Blunt on 11 November 1979. Image: Keystone Press / Alamy Stock Photo

Blunt died at his London home in Highgate in 1983, at the age of 75. The historical debate continues as to the human cost resulting from his espionage, and the extent of the damage he may have caused to military operations during the Second World War.