Record revealed

An unusual royal gift to the poet Geoffrey Chaucer

How do you reward a medieval poet? This document granted the author of the Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer, a rather unusual royal gift: a daily allowance of wine. We know he owned, handled, and used it.

Image 1 of 4

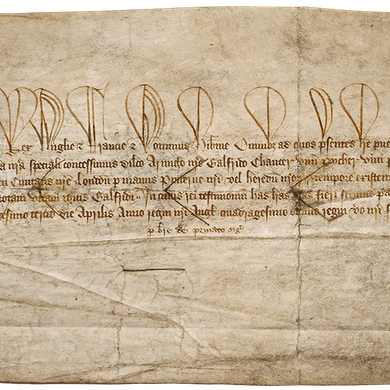

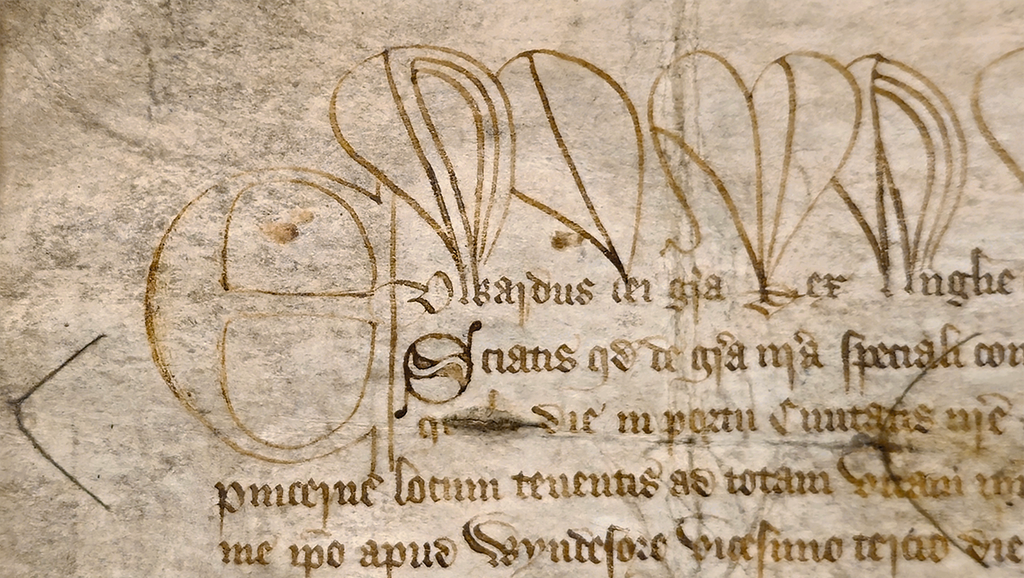

Letters patent granting Geoffrey Chaucer a daily pitcher of wine.

Transcript

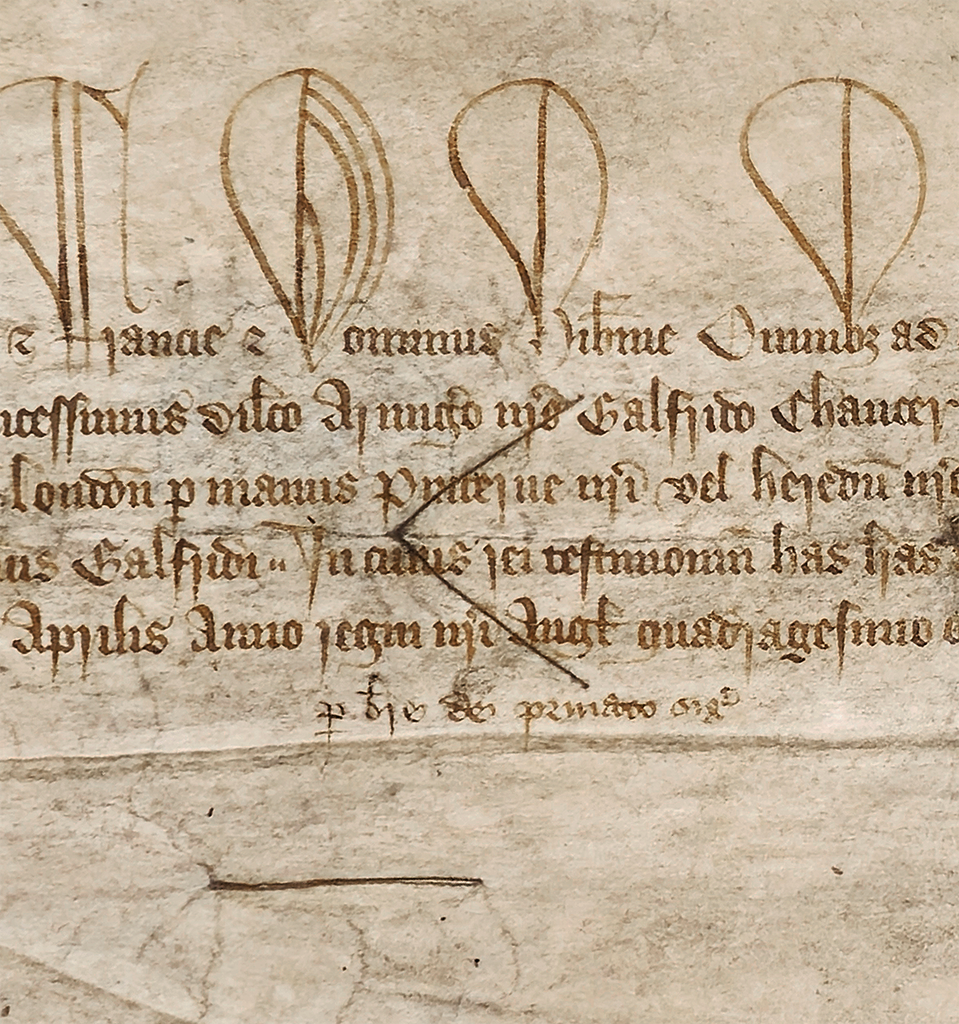

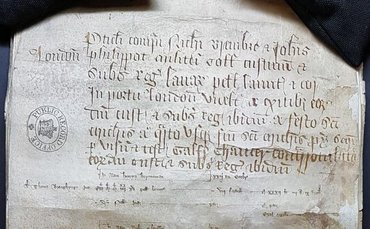

Edwardus dei gracia rex Anglie et Francie et dominus Hibernie omnibus ad quos presentes littere pervenerint salutem. Sciatis quod de gracia nostra speciali concessimus dilecto armigero nostro Galfrido Chaucer unum picher vini percipiendum qualibet die in portu civitatis nostre Londonie per manus pincerne nostri vel heredum nostrorum pro tempore existentis vel eiusdem pincerne locum tenentis ad totam vitam ipsius Galfridi. In cuius rei testimonium has litteras nostras fieri fecimus patentes. Teste me ipso apud Windesore vicesimo tercio die Aprilis anno regni nostri Anglie quadragesimo octavo regni vero nostri Francie tricesimo quinto

Per breve de private Sigillo – Muskham

Translation

Edward, by the grace of God, king of England and France, and lord of Ireland, to all whom these present letters may come, greeting. Know that by our special grace we have granted to our beloved esquire Geoffrey Chaucer one pitcher of wine to be received every day in the port of our City of London by the hands of our butler or our heirs for the time being or holding the place of the same butler, for the whole life of Geoffrey himself. In witness whereof we have made these our letters patent. Witnessed by myself at Windsor on the twenty-third day of April in the forty-eighth year of our reign of England and the thirty-fifth of our reign of France.

By writ of privy seal – Muskham

Image 2 of 4

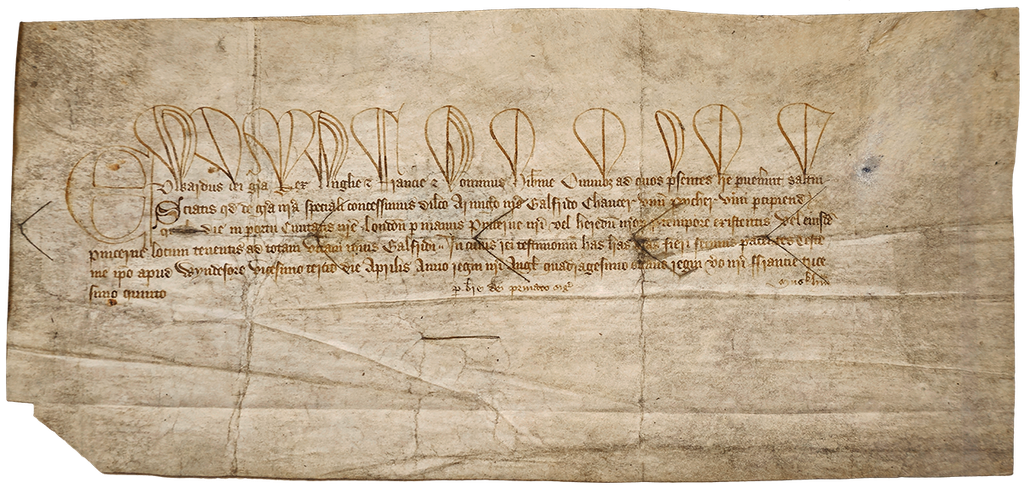

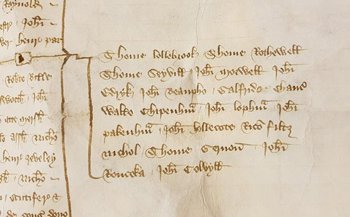

Close up of the section ‘Galfrido (Geoffrey) Chaucer one pitcher of wine’ .

Image 3 of 4

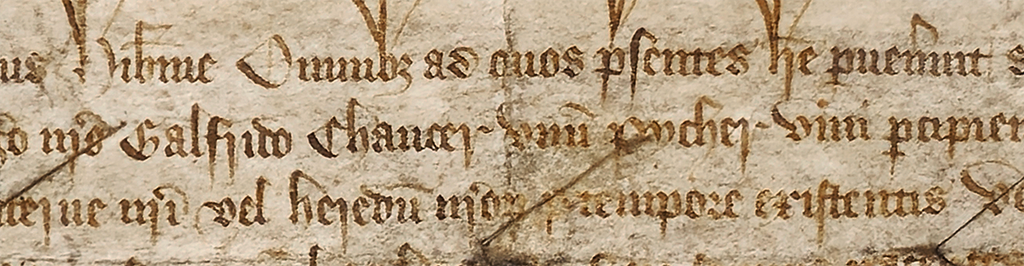

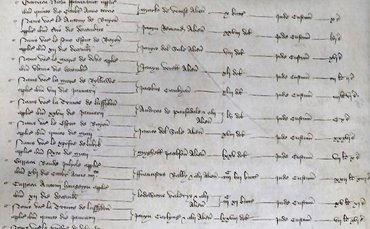

Close up of one of the chevrons cancelling the text, and a slit where the Great Seal would have been attached.

Image 4 of 4

Close up of the decorated first initial, and name of Edward III.

Why this record matters

Date: 23 April 1374 (St George’s Day)

These letters patent – written orders or grants from the monarch – were presented to the medieval poet Geoffrey Chaucer by King Edward III, on St George’s Day (23 April) 1374. Chaucer was granted a daily pitcher of wine, probably equivalent to a gallon, which was to be redeemed by the king’s butler at the Port of London each day.

Though not common, wine was not a rare royal gift, but grants were normally made in the form of a barrel (or barrels) to be redeemed each year. The grant of a single pitcher daily was unusual, and it has been suggested that the wine may have been a gift to Chaucer in reward for a performance at the annual St George’s Day feast, as an early form of poet laureate, although this is not stated in the document.

From 8 June 1374 Chaucer’s primary employment was as Controller of the Port of London, auditing the accounts of the customs collectors there. As such, he would easily have been able to redeem his gift each day at his place of work. This was Chaucer's first appointment to what we might consider the medieval civil service, a role which he held for twelve years.

What is particularly interesting about this document is that it is one of very few records about Geoffrey Chaucer that we know the poet himself would have held and used. It might even be the only one. These are the original letters patent granted to Chaucer, which he would have presented as evidence of his gift when claiming it at the Port of London. Normally such records were retained by the individual who received them, and at The National Archives we only hold official copies of their content, recorded during the course of their production.

Four years after they had been granted, however, Chaucer returned his original letters, converting his daily pitcher of wine into a cash payment of 20 marks per year, to be received at the Exchequer. The letters patent of 1374 were filed alongside a warrant to issue new letters patent in 1378, confirming his new cash gift, and the first set of letters were cancelled. The Great Seal, which would have been attached by a seal tag (located at the horizontal cut in the middle of the document, under the text) was removed, and the text was crossed through with a series of chevrons to mark the cancellation. A note on the reverse of the letters also recorded the cancellation and the issuing of new letters patent.

Was this a better deal for him? As the son of a successful wine merchant, Chaucer would probably have known what he was doing.

Blogs and podcasts

-

Blog: The civil servant’s tale – Geoffrey Chaucer in the archives

By Euan Roger – 30 October 2017

The National Archives holds more than 500 records of Geoffrey Chaucer’s life. What do they reveal about his activities and career?

-

Blog: A world of wine and taxes

By Keith Mitchell – 23 May 2019

Dip into a range of intriguing records about our enjoyment of wine. And surprise, surprise – Chaucer makes an appearance...

-

Blog: The Alchemist’s Tale – Geoffrey Chaucer and alchemy

By Euan Roger – 9 October 2019

Where did Chaucer get the inspiration for his stories? The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale may have been based on a real-life trial...