Record revealed

A letter from Gandhi's 'errand boy'

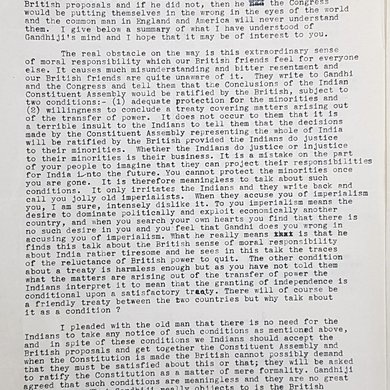

This record is an example of those in our collection detailing Indian and Pakistani Independence, but from a lesser-known voice – Gandhi’s confidante, Sudhir Ghosh. His letter sheds light on the complex and entangled world of politics where negotiations took place.

Image 1 of 2

Sudhir Ghosh's letter to British MP Sir Stafford Cripps.

Partial transcript

I had a talk with the Secretary of State before I left Delhi and on my arrival here I had a long talk with Gandhiji. My purpose was to try and understand the gulf that separates the two sides and whether the gulf was, in the present circumstances, at all bridgeable. I was also anxious to explain to the old man my own conviction that he should advise the Congress to accept the British proposals and if he did not, then he and Congress would be putting themselves in the wrong in the eyes of the world and the common man in England and America will never understand them. I give below a summary of what I have understood of Gandhiji’s mind and I hope that it may be of interest to you.

The real obstacle on the way is this extraordinary sense of moral responsibility which our British friends feel for everyone else. It causes much misunderstanding and bitter resentment and our British friends are quite unaware of it. They write to Gandhi and the Congress and tell them that the conclusions of the Indian Constituent Assembly would be ratified by the British, subject to two conditions:- (1) adequate protection for the minorities and (2) willingness to conclude a treaty covering matters arising out of the transfer of power. It does not occur to them that it is a terrible insult to the Indians to tell them that the decisions made by the Constituent Assembly representing the whole of India would be ratified by the British provided the Indians do justice to their minorities.

Image 2 of 2

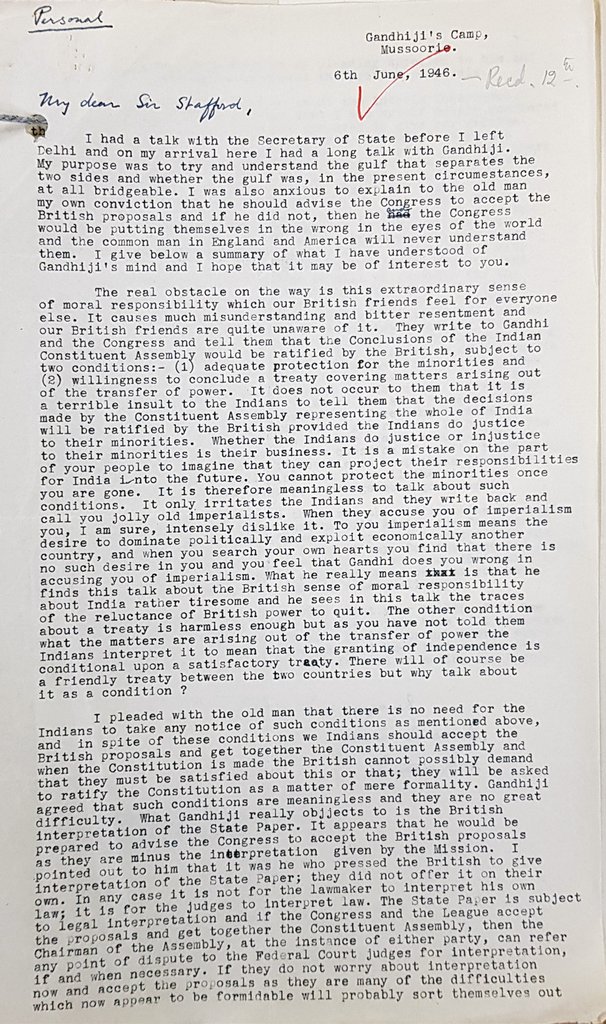

Page two of Sudhir Ghosh's letter.

Partial transcript

I tried to explain to the old man that I was myself deeply convinced that although the British were not prepared to give any written assurance about the powers of the interim government there was really not the slightest desire in them to interfere and that there was no doubt the new Indian government would be allowed to function as a real government (for all practical purposes as a dominion government). Gandhiji agreed that I was right, and he does not require any further satisfaction on that point. But he fears that difficulty about the interim government will come in another way...

As far as I can understand these are the difficulties Gandhiji has in his mind. I still have hopes that he will advise the Congress to accept the British proposals. I have done my best to argue with him and he carefully listened to all I had to say. But the Congress people are going to meet on Sunday and they will let you know their mind by Monday. I am writing this letter entirely on my own. As you know, my only desire is to help, if I can in some small way.

Gandhiji made anxious enquiries about your health. I do hope you are yourself again by now and the voyage home will restore your former health. I got news of your health through George every now and then but did not try and see you as I knew that seeing people would be a strain on you. I shall look forward to seeing you before you go home.

Why this record matters

Date: 6 June 1946

Sudhir Ghosh, Mahatma Gandhi's confidante and self-proclaimed 'errand boy', wrote this letter to British MP Sir Stafford Cripps. Cripps was part of Britain's Cabinet Mission sent to India on 24 March 1946, to discuss and agree a process for the transfer of power from the British government to Indian political leadership. Cripps organised negotiations with the leading Indian political parties, the Indian National Congress, and the Muslim League.

Ghosh's words, written during the height of negotiations, provide a front-row seat to the talks, revealing tensions on all sides. When reading the content of the letter, it's easy to forget it's not authored by Gandhi, but by Ghosh, who says it's written 'entirely on my own' but that the letter gives 'a summary of what I have understood of Gandhiji’s [Gandhi's] mind'. Gandhi described Ghosh as a 'reliable and steady bridge between Great Britain and India'.

The focus of the letter is Ghosh’s conviction that the Indians should accept the British proposals, which fall short of calling for the division of India, but do suggest power will need to be shared in ways he fears will be unacceptable to the Indian National Congress. He says, 'I still have hope that he [Gandhi] will advise the Congress to accept'. Ghosh argues that Indians want to govern their own country, and despite the differences between the leading parties, they should be left alone to work it out for themselves.

At times the letter takes an informal tone, with Ghosh referring to Gandhi as 'old man', but it's evident he's enamoured by the company he's keeping as seen in his use of the honorific 'ji'. Interestingly, Ghosh inserts himself into the negotiations in ways that have either been forgotten or not previously highlighted, writing 'I have done my best to argue with him [Gandhi] and he carefully listened to all I had to say'.

He also makes the eye-catching assertion, which he says conveys Gandhi's thoughts, that 'the real obstacle on the way is this extraordinary sense of moral responsibility which our British friends feel for everyone else. It causes much misunderstanding and bitter resentment'.

A passage at the end of the letter paints an alternative picture to the divisive politics of the time, with Ghosh and Gandhi both asking after the health of Cripps suggesting a level of familiarity between them. He adds, 'I shall look forward to seeing you before you go home'.

Despite Ghosh's views, the 1946 Cabinet Mission's proposals didn't find common ground between the parties and failed to secure an agreement. The mission left India on 29 June 1946, unsuccessful.