Match making

In the 1880s the Bryant & May match factory was one of the most significant employers in London’s East End. Several thousand people worked in an imposing building that covered acres of land in Bow.

The match-making trade was booming – matches were key to lighting the nation's homes and providing warmth. It was also a significant export business and important to the economy.

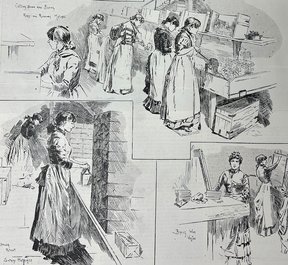

Sketches at Bryant and May’s Match Manufactory, Illustrated London News, 4 August 1888. Catalogue reference: ZPER 34/93.

At the time it was not uncommon for children to work in factories. In areas of extreme poverty, everyone in the family was needed to add to the household income. At Bryant & May girls and boys as young as 14 were regularly employed. Casual and sweated labour, marked by irregular work and poor conditions, was common.

‘Matchgirls’ is a term used to refer to women and teenage girls who did various jobs in the factory, including dipping, wrapping, cutting down and boxing matches.

Factory conditions

The factory conditions were notoriously awful. Bryant & May had a monopoly on the market and were therefore able to get away with bad pay and conditions.

'The Little Match Girl', a photograph registered for copyright in 1890, shows the Thames Embankment with a matchgirl sleeping. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/401/61.

On top of long hours and poor pay was a system for docking wages. Matchgirls would be fined at the discretion of the factory foremen, for example if their feet were dirty or for an untidy workbench. There were even some fines for talking. This was a common but controversial practice, as various observations from factory inspectors across the country show.

The authorities were aware of this at Bryant & May, and records indicate they considered whether this breached the Truck Acts. This legislation aimed to protect workers’ pay – ensuring it was the full agreed amount and not subject to conditions. An amendment in 1887 extended the act to cover more workers.

Phossy jaw

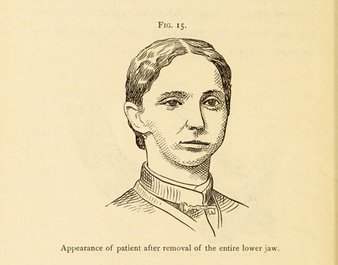

The factory conditions at Bryant & May were also dangerous, due to exposure to white (also called yellow) phosphorous. White phosphorous was used to make popular lucifer matches, which were easier to light than safety matches. The fumes were poisonous and workers could develop phosphorus necrosis of the jaw. Known as ‘phossy jaw’, the disease affected the teeth, gums, face and could cause brain damage.

Illustration of a young woman who has lost part of her face to phossy jaw. Public domain. Phosphorus-necrosis of the jaws by J. Ewing Mears, 1886. Source: Wellcome Collection.

An article from 1898 in The Daily Chronical described phosphorus poisoning as ‘one of the most terrible and painful diseases to which the workers are subject.’ The various roles of matchgirls meant they regularly interacted with these harmful chemicals. A report from 1893 noted ‘Insufficient food’ meant workers were less nourished and therefore had a ‘small power of resistance’ to fight off the disease. Poor dental hygiene among the working class also made them more vulnerable. A report covering 1882 to 1897 documented that the mortality rate in cases of phossy jaw at Bryant & May was 19.15% – almost one in five.

By this time there was some regulation under the Factory Act 1878, but it was very limited compared to the provisions in other countries. The practice of using white phosphorus was becoming increasingly controversial, especially as red phosphorous did not have the same horrific impact, but could be used to make safety matches.

Annie Bessant

The Fabian Society were one of the groups concerned about the conditions and pay at Bryant & May, particularly in light of significant shareholder profits. One of the advocates for the matchgirls was socialist, Fabian and theosophist Annie Besant (1847–1933), described on the 1881 census as a political author.

Photograph of Annie Besant, registered for copyright 1885. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/374/382.

Bessant decided to speak directly to the affected workers, obtaining details of their wages, working conditions and fines. The result was an article entitled ‘White slavery in London’, through which she exposed the shocking conditions the matchgirls were subject to. The title of the article was deliberately sensationalist to attract attention. It is now a very problematic title – these women were low paid and poorly treated, but not enslaved.

Bessant’s article shows her primary aim was a boycott of Bryant & May. It also tried to provoke libel action – essentially meaning Bryant & May would have to disprove the statements made. Instead, inspired by the article and the harsh reality of the conditions they faced, the matchgirls took their own decisive action.

The strike

Management at Bryant & May pressured the women workers to contradict what Bessant had published, but they refused. The factory management sacked or gave very minimal work to several matchgirls seen as being involved.

In response 1400 women walked out of work, and a few days later the whole factory had ground to a halt. The factory managers reinstated the sacked employee, but the matchgirls used their power to negotiate on other issues affecting them in the workplace, most significantly the fining system.

Sarah Chapman (1862–1945) was one of the known strike leaders. The census shows she was a match-making machinist from at least the age of 19, along with her mother and sister.

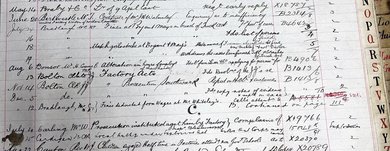

The Home Office were clearly concerned about these developments, as seen through their Registers of Daily Correspondence, which note the matchgirl strike. Unfortunately, the original letters do not appear to survive.

Home Office daily registers of correspondence from May to August 1888. Letters on the subject of 'Fines at Bryant and May's in breach of Truck Act' and 'Match girls strike at Bryant and May's' are listed. Catalogue reference: HO 46/93.

In Parliament Charles Bradlaugh advocated for the workers. Mass meetings were held, marches made to Parliament and funds raised in support of the strikers. Eventually, the workers’ immediate demands concerning the sacked of employee and docking of pay were won and the strike ended.

After the 1888 strike, the Union of Women Match Workers was formed, with Bessant as Secretary. Strike leader Chapman was elected to the committee and made President.

New Unionism

The 1888 matchgirls' strike was a powerful example of the impact workers could have by withdrawing their labour. This was one of the first times a union of so-called ‘unskilled workers’ – rather than a ‘skilled worker’ of a specific trade – had succeeded in striking for better pay and conditions.

Members of the Matchmakers' Union. Public Domain. Source: Wellcome Collection.

The year following the matchgirls' strike saw more action by workers, including the London strike of gas workers and the London dock strike, bringing out thousands of workers. This was a significant moment in the labour movement, which has since been termed New Unionism. It was characterised by a more radical approach, greater willingness to strike, higher membership density and an appeal to a wider reach of workers outside traditional craft-based unions.

Working women and girls, some as young as 14, had started this wave of unrest and change in the labour movement.

Legacy of the strike

The matchgirl strike added to the growing public conversation around the use of white phosphorus and the practice of fining, giving the plight of workers more direct visibility. While the practice of wage docking stopped at Bryant & May after the strike, the use of white phosphorus continued.

Transcript

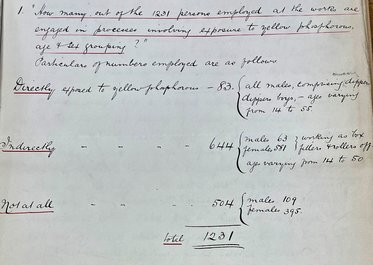

“How many, out of the 1231 persons employed at the works are engaged in processes involving exposure to yellow phosphorous, age and sex grouping?”

Particulars of numbers employed are as follows.

Directly exposed to yellow phosphorous – 83 (all makes, comprising dippers, dippers boys – ages varying from 14 to 55)

Indirectly – 644 (males 63, females 581 working as box fillers and rollers off, ages varying from 14 to 50)

Not at all – 504 (males 109, females 395)

Total 1231

“How many, out of the 1231 persons employed at the works are engaged in processes involving exposure to yellow phosphorous, age and sex grouping?”

Particulars of numbers employed are as follows.

Directly exposed to yellow phosphorous – 83 (all makes, comprising dippers, dippers boys – ages varying from 14 to 55)

Indirectly – 644 (males 63, females 581 working as box fillers and rollers off, ages varying from 14 to 50)

Not at all – 504 (males 109, females 395)

Total 1231

Inspection report from 1898 detailing the number of people working directly and indirectly with white phosphorus at Bryant & May, with gender and age details. Catalogue reference: HO 45/9849/B12393D.

However, by this point it had become a key concern of the Home Office. The Factories Act enabled the government to introduce special rules when it was necessary, and the continuing illness and deaths caused by phossy jaw drove the government to implement this power.

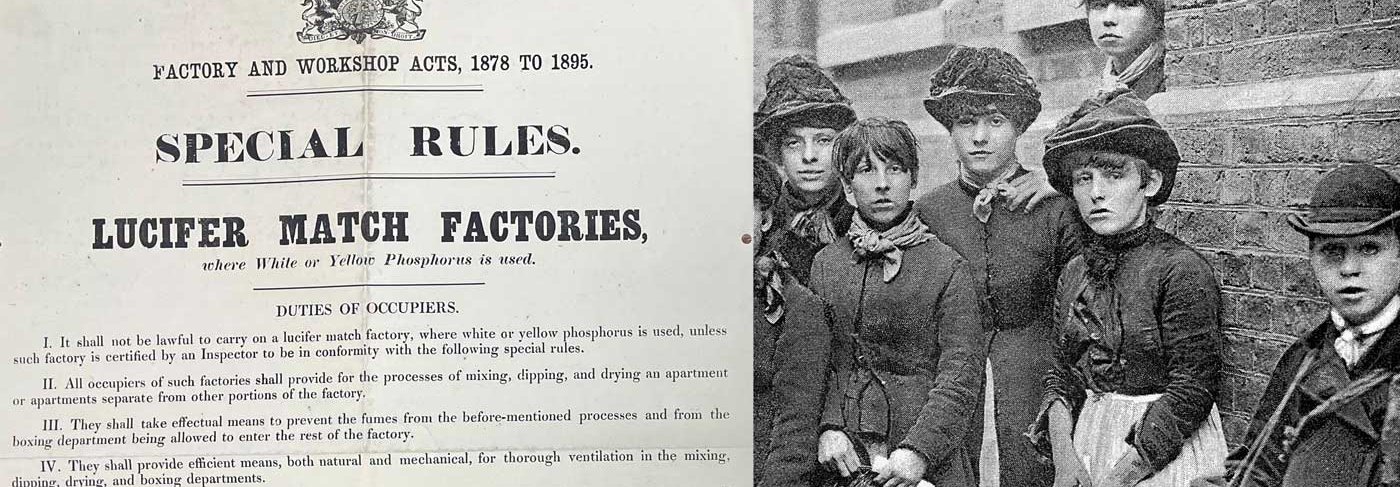

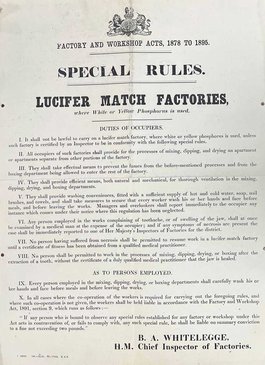

In 1893 Special Rules were introduced to 22 lucifer match factories, 18 of which were in England. These factories had to be certified, sanitation provisions provided and better ventilation introduced. Our files reveal lots of objections from factories, who felt it would be disruptive to their work and that the mandated medical examinations would be costly.

Partial transcript

Special rules

Lucifer match factories, where White or Yellow Phosphorous is used.

Duties of occupiers

I. It shall not be lawful to carry on a lucifer match factory, where white or yellow phosphorous is used, unless such factory is certified by an Inspector to be in conformity with the following special rules

[…]

V. They shall provide washing conveniences, fitted with a sufficient supply of hot and cold water, soap, nail brushes, and towels, and shall take measures to secure that every worker wash his or her hands and face before meals, and before leaving the works. Managers and overlookers shall report immediately to the occupier any instance which comes under their notice where this regulation has been neglected.

VI. Any person employed in the works complaining of toothache, or of swelling of the jaw, shall at once be examined by a medical man at the expense of the occupier; and if any symptoms of necrosis are present the case shall be immediately reported to one of Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Factories for the district.

VII. No person having suffered from necrosis shall be permitted to resume work in a lucifer match factory until a certificate of fitness has been obtained from a qualified medical practitioner.

VIII. No person shall be permitted to work in the processes of mixing, dipping, drying, or boxing after the extraction of a tooth, without the certificate of a duly qualified medical practitioner that the jaw is healed.

Special rules

Lucifer match factories, where White or Yellow Phosphorous is used.

Duties of occupiers

I. It shall not be lawful to carry on a lucifer match factory, where white or yellow phosphorous is used, unless such factory is certified by an Inspector to be in conformity with the following special rules

[…]

V. They shall provide washing conveniences, fitted with a sufficient supply of hot and cold water, soap, nail brushes, and towels, and shall take measures to secure that every worker wash his or her hands and face before meals, and before leaving the works. Managers and overlookers shall report immediately to the occupier any instance which comes under their notice where this regulation has been neglected.

VI. Any person employed in the works complaining of toothache, or of swelling of the jaw, shall at once be examined by a medical man at the expense of the occupier; and if any symptoms of necrosis are present the case shall be immediately reported to one of Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Factories for the district.

VII. No person having suffered from necrosis shall be permitted to resume work in a lucifer match factory until a certificate of fitness has been obtained from a qualified medical practitioner.

VIII. No person shall be permitted to work in the processes of mixing, dipping, drying, or boxing after the extraction of a tooth, without the certificate of a duly qualified medical practitioner that the jaw is healed.

Poster outlining the Special Rules for Lucifer Match Factories where white or yellow phosphorus is used, as issued by the Chief Inspector of Factories, 1893. Catalogue reference: HO 45/9849/B12393D.

The special rules also introduced compulsory reporting of phosphorus poisoning to factory inspectors. Despite this extra regulation, the cases of phossy jaw continued to be underreported and caused controversy in the press.

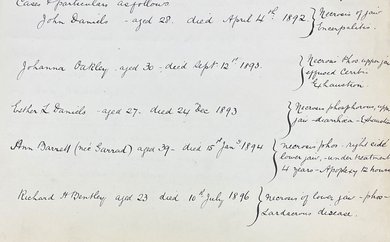

Bryant & May came to the Home Office’s attention repeatedly and records show at least five deaths of factory workers from consequences of phosphorus poisoning between 1892 and 1896. Records also include a list of 11 Bryant & May employees all continuing to suffer from phossy jaw by 1898. The youngest, aged 19, had worked for five years at the factory.

Match workers also had an obligation to report health concerns. However, many feared this because if they showed symptoms, they would be forced to stop working.

Partial transcript

John Daniels – aged 28 – died April 4th 1892

Johanna Oakley – aged 30 – died Sept 12th 1893

Esther L Daniels – aged 27 – died 24th Dec 1893

Ann Barrell (nee Garrad) aged 39 – died 15th Jan 1894

Richard H Bentley aged 23 died 10th July 1896

John Daniels – aged 28 – died April 4th 1892

Johanna Oakley – aged 30 – died Sept 12th 1893

Esther L Daniels – aged 27 – died 24th Dec 1893

Ann Barrell (nee Garrad) aged 39 – died 15th Jan 1894

Richard H Bentley aged 23 died 10th July 1896

List of five match workers who had died from phosphorus poisoning at Bryant & May, from 1892 to 1896. Catalogue reference: HO 45/9849/B12393D.

Further special regulations and the Factory & Workshop Acts were introduced, offering more worker protection. However, employers could argue against special regulations through arbitration, which many match factories did. The Union of Women Match Makers became the Matchmakers' Union and in 1900 they demanded to be part of the arbitration process, arguing that workers' voices needed to be heard.

Despite all this the government were reticent to ban white phosphorus, trying to avoid overregulation of industry and recognising the economic significance of the match trade. Many of the shareholders of Bryant & May were also notable figures at the time, including politicians.

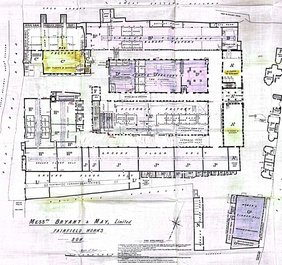

Plan of Bryant & May factory, Fairfield Works, Bow around 1899 to 1900 showing changes in the grounds to adapt to Special Rules. Four of the buildings contained phosphorus processes. Catalogue reference: TS 18/425.

Despite the significant impact on their workers, Bryant & May continued to argue against a ban. By 1901, technological advances meant other production options were available for easy-strike matches and Bryant & May finally announced that they would no longer be using white phosphorus. A government ban followed a few years later.

The matchgirls were vital in creating visibility for the match workers’ plight. Their strike added momentum to the trade union movement and helped working class people in the East End recognise their own power to make change.

Records featured in this article

-

- Title

- Illustrated London News

- Date

- 4 August 1888

-

- Title

- Photograph of 'The Little Match Girl'

- Date

- 1890

-

- Title

- Photograph of Annie Besant

- Date

- 1885

-

- Title

- Home Office daily registers of correspondence

- Date

- May to August 1888

-

- Title

- Plan of Bryant & May factory

- Date

- 1899–1900