Wicked little letters: The Littlehampton libel case

Littlehampton neighbours Edith Swan and Rose Gooding were embroiled in a 1920s scandal when Edith accused Rose of sending obscene letters. Edith’s accusations put Rose in prison, but was she really guilty? Dramatised in the film Wicked Little Letters, documents in our collection show the real story.

Important information

One of the documents pictured, listing charges from December 1921, contains strong language.

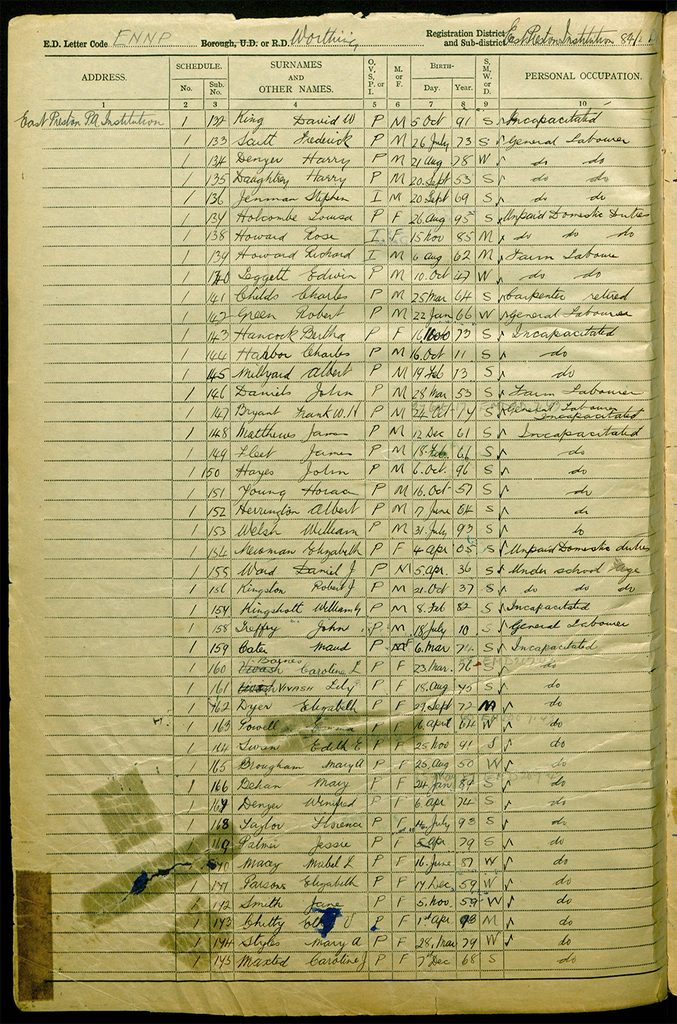

Newspaper photographs showing people involved in the Littlehampton libel case

Date: October 1921

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

The case of the Littlehampton letters involved four court cases, three prison sentences and two close neighbours, Edith Swan and Rose Gooding.

Along the way it enveloped Edith and Rose’s families, friends and neighbours and continued over a period of almost three years.

These photographs were printed in the Daily Mirror in October 1921 and show the various people involved in the scandal at that time.

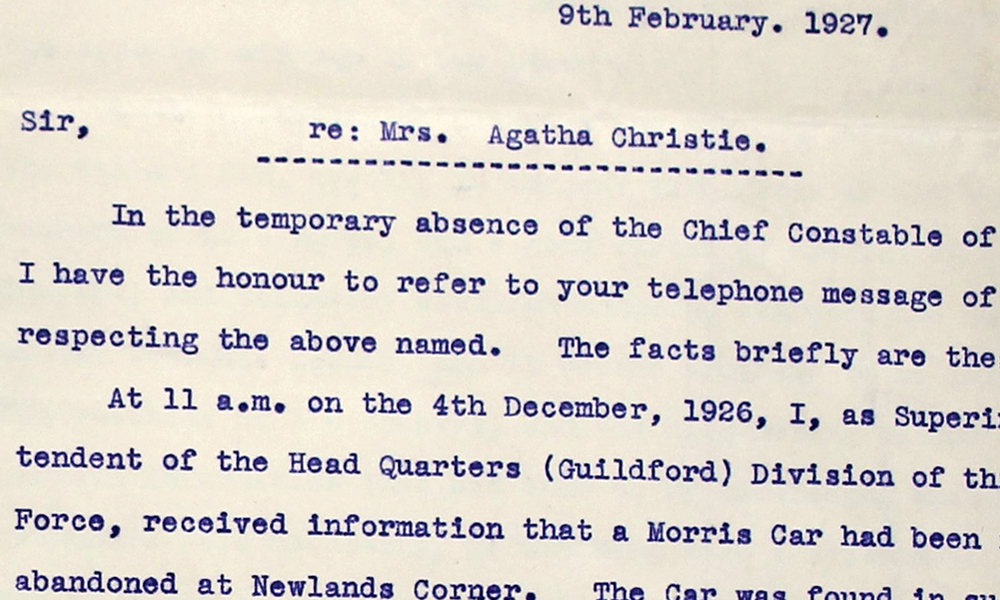

Calendar of prisoners from Sussex assizes showing Rose Gooding’s libel conviction

Date: December 1920

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

Edith and Rose had been on friendly terms since becoming neighbours, but the relationship soured when Edith reported Rose to the NSPCC for the way she treated her sister’s child. Investigations found Rose was not at fault, but soon afterwards Edith and other neighbours began receiving letters containing obscene language and libellous allegations.

Suspicion fell on Rose, and despite a lack of evidence, on 22 September 1920 magistrates committed her for trial. Rose was kept in prison until 13 December, when her case was heard at the next assizes, regional courts that sat periodically rather than permanently.

This Home Office document lists prisoners that were tried at Sussex assizes in 1920. Rose Gooding is shown as having been found guilty of ‘Publishing defamatory libels concerning Edith Emily Swan, well knowing the same to be false’. Rose was sentenced to a further 14 days in prison.

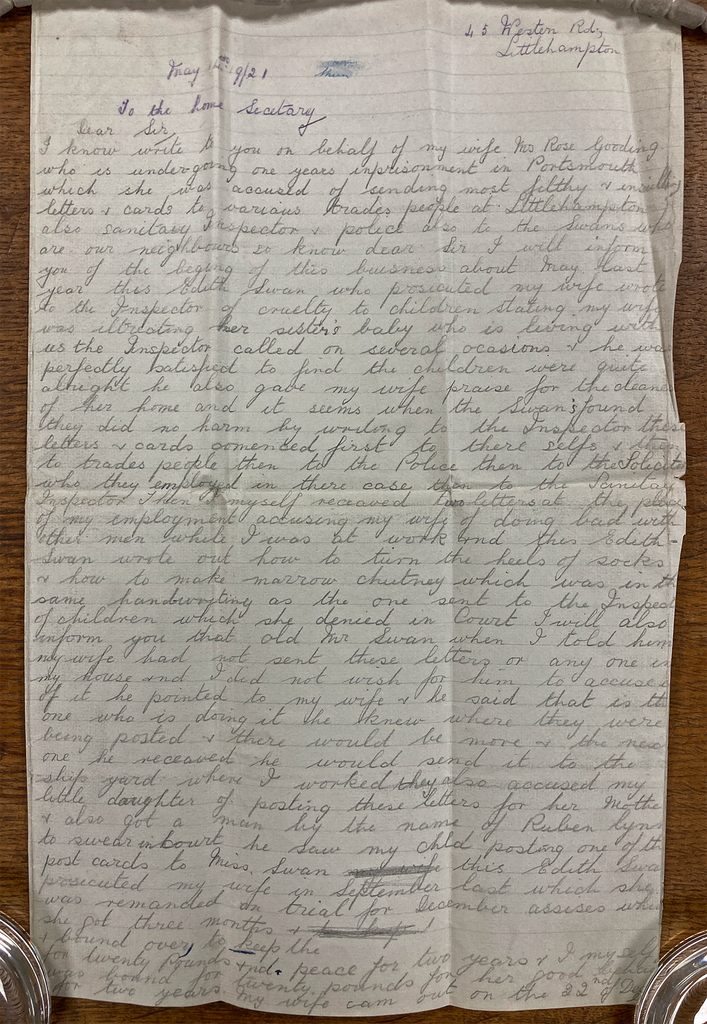

Letter from William Gooding to the Home Secretary proclaiming Rose’s innocence

Date: May 1921

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

This letter was written by Rose Gooding’s husband, William, to the Home Secretary when Rose was sent to prison for a second time.

After Rose’s release from her sentence on 23 December 1920, the obscene letters had started again, leading to a second trial for Rose in March 1921. It took the jury only half an hour to reach a guilty verdict, and this time Rose was sentenced to 12 months in prison.

William wrote to the Home Secretary in May protesting his wife’s innocence and claiming that the obscene letters started after Edith’s complaint to the NSPCC came to nothing. William said that as well as the Swans, letters were received by tradespeople, the police, a solicitor and the Sanitary Inspector. William also received two letters himself ‘at the place of my employment, accusing my wife of doing bad with other men while I was at work’.

Did it really make sense that Rose was the culprit?

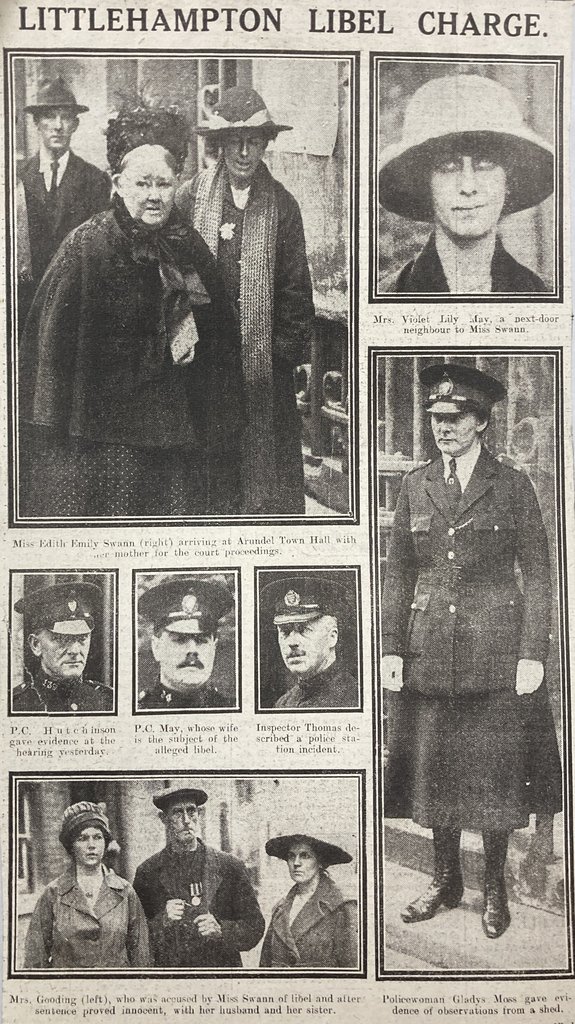

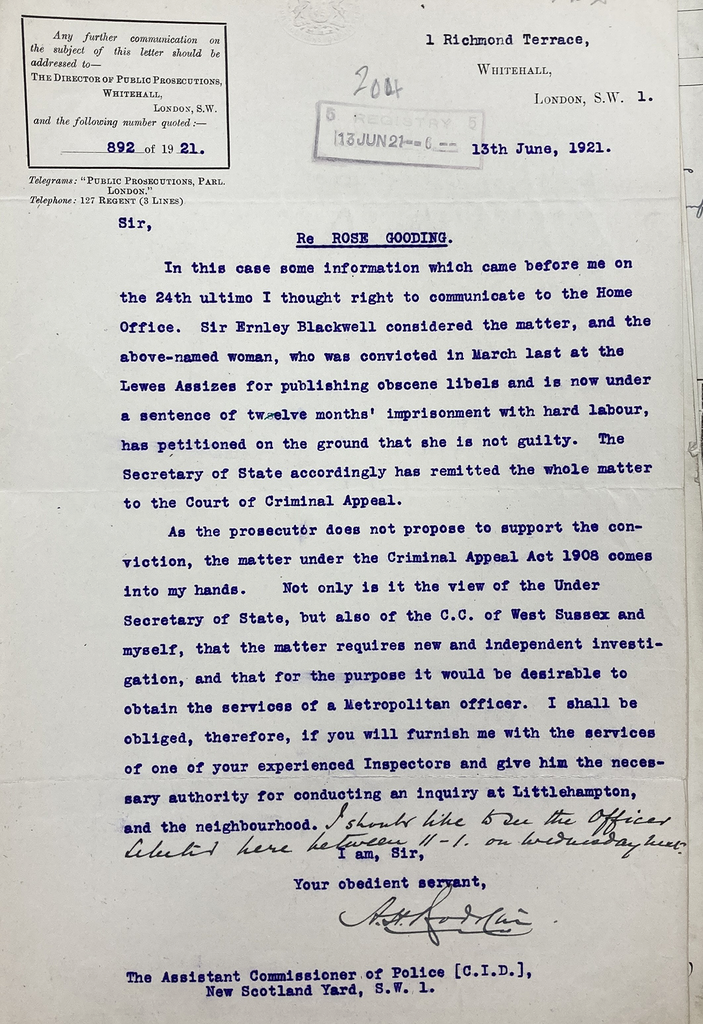

Letter from the Director of Public Prosecutions requesting assistance from the Met Police

Date: 13 June 1921

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

Rose appealed against her conviction, leading Leonard Kershaw, Clerk of the Court of Criminal Appeal, to review her convictions and raise his concerns with the Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Archibald Bodkin.

In this letter dated 13 June 1921, Sir Archibald wrote that he and the West Sussex Chief Constable (Captain Arthur Williams) were both of the view that ‘the matter requires new and independent investigation’.

Sir Archibald asked the Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police to send one of his officers to carry out enquiries in Littlehampton. Inspector George Nicholls was assigned to the case, travelling to Littlehampton on 17 June.

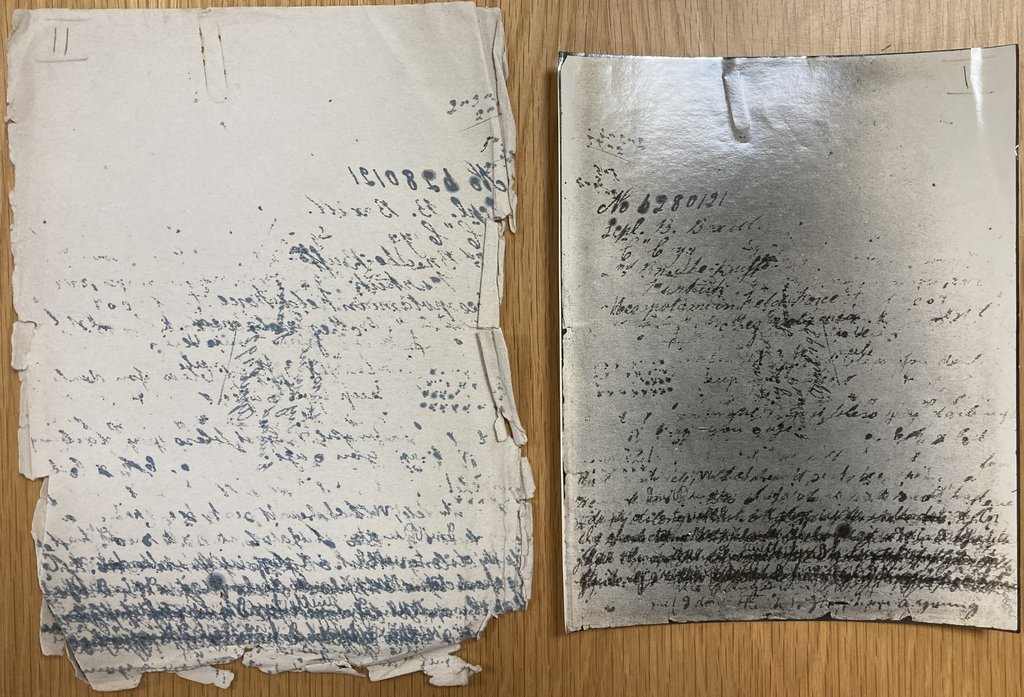

Blotting paper images of handwriting found in Edith’s house

Date: July 1921

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

On 2 July 1921 Inspector Nicholls reported on his examination of blotting paper found in Edith Swan’s home.

Blotting paper was used to absorb ink on handwritten letters that might otherwise have smudged. Images on blotting paper show the original writing in reverse, so to make them legible, the police took photographs which were in turn reversed and then printed. This made it easier to compare the handwriting with that on the malicious letters.

Nicholls wrote in his report ‘I have found nothing that would in my opinion agree with Mrs Gooding’s writing or in fact any of the Gooding family’. Instead, Nicholl reported that the writing on the blotting paper ‘has the same characteristics as the obscene postcards and letters’ implying that whoever wrote them had used the blotting paper in the Swan household.

A few weeks later on 25 July Rose’s appeal succeeded, and her convictions were quashed.

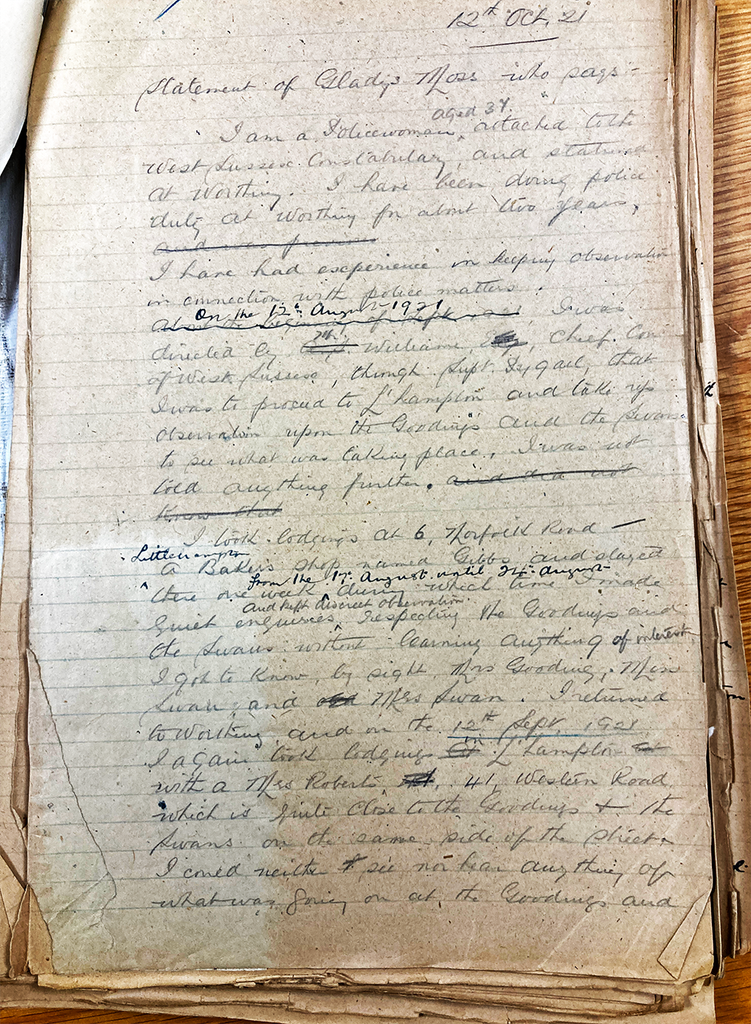

Statement by police constable Gladys Moss

Date: October 1921

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

Gladys Moss was the first female police constable to be appointed to the West Sussex Constabulary, taking on the role in 1919. She was stationed at Worthing and focused on cases involving women and children.

In August 1921, Gladys was sent to Littlehampton to ‘take up observation on the Goodings and the Swans to see what was taking place’, but after a week she had not seen anything untoward. She returned in September and this time she worked with police officer George May who was a neighbour of Edith and Rose. George and his wife Violet had also received obscene letters.

On 27 September Gladys spotted Edith dropping a note in the area of the shared yard where she and Violet May hung their washing. Gladys sent Violet to retrieve the note and discovered it contained obscene insults aimed at the Mays.

Edith was caught red handed.

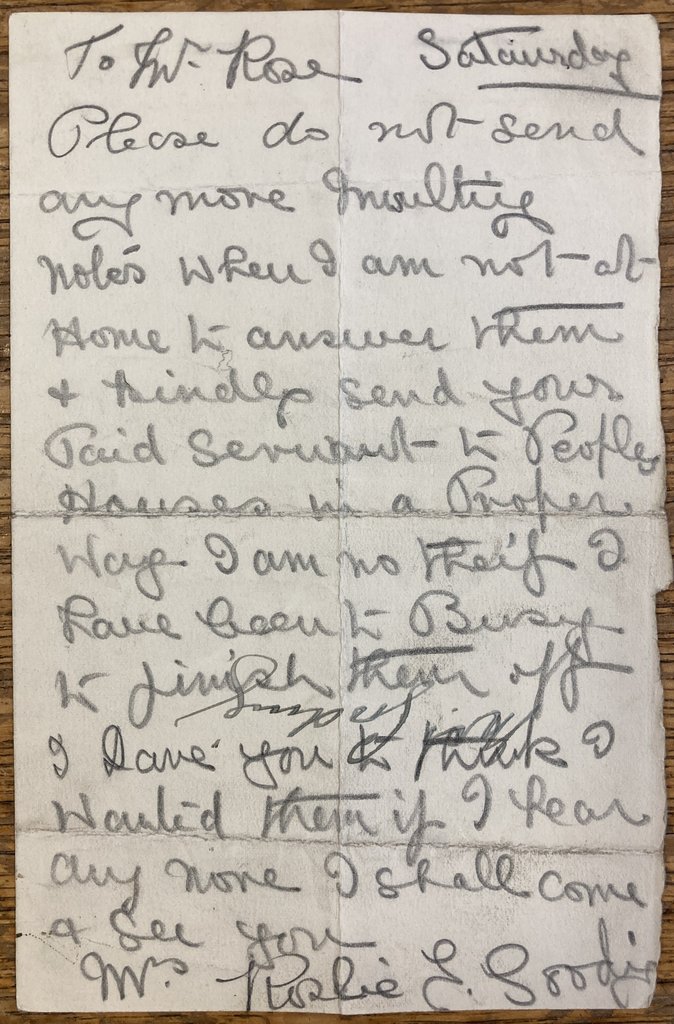

Handwritten letter from Rose Gooding to George Rose, a former employer

Date: January 1920

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

Rose had been employed by local publisher George Rose and his wife, to help with domestic chores including sewing repairs. However, following a dispute in January 1920, George Rose had sent a servant with a note demanding the return of various items of clothing Rose had been mending. Rose’s spirited handwritten response read:

‘Please do not send any more Insulting notes when I am not Home to answer them & kindly send your Paid Servant to Peoples Houses in a Proper way. I am no theif I have been to Busy to finish them off I dare you to think I wanted them if I hear any more I shall come & see you’

A Home Office note suggests that Rose’s letter showed she was capable of the crimes she had been accused of, but also that ‘There is a world of difference between writing a rude note to her late mistress about some underclothing which she had been repairing and composing these filthy libels’.

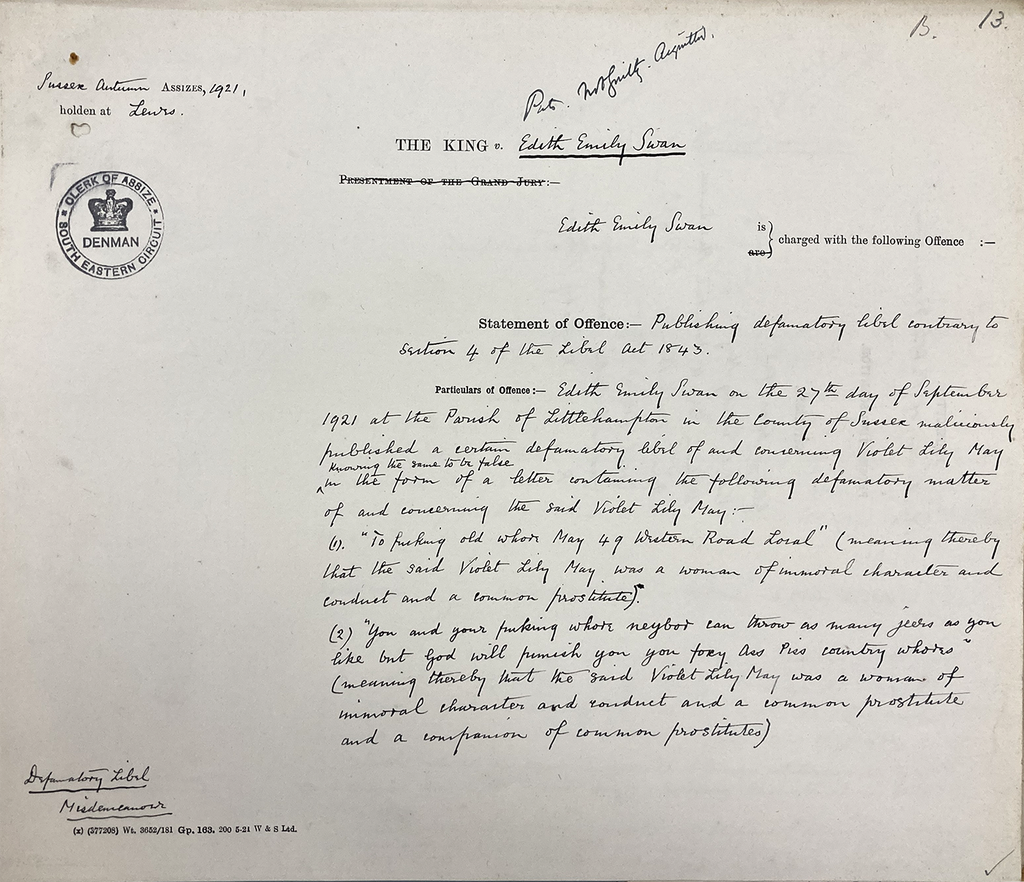

Sussex Autumn assizes indictments 1921, showing the charges against Edith Swan

Date: December 1921

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

Following the work of Gladys Moss, Edith was sent for trial at the Lewes assizes in December 1921. The indictment read:

‘Edith Emily Swan on the 27th September 1921 in the Parish of Littlehampton in the County of Sussex maliciously published a certain defamatory libel of and concerning Violet Lily May knowing the same to be false in the form of a letter’

The trial did not go as the prosecution hoped. The defence claimed that Gladys Moss had a limited field of vision from her surveillance point, and that someone could have thrown the letter into the shared yard without her seeing them. When Edith gave evidence herself, she was asked about the blotting paper and she claimed that her father had found it in the shared wash house, implying that it could have been Rose that had left the incriminating ink impressions on it.

The trial collapsed and Edith walked free.

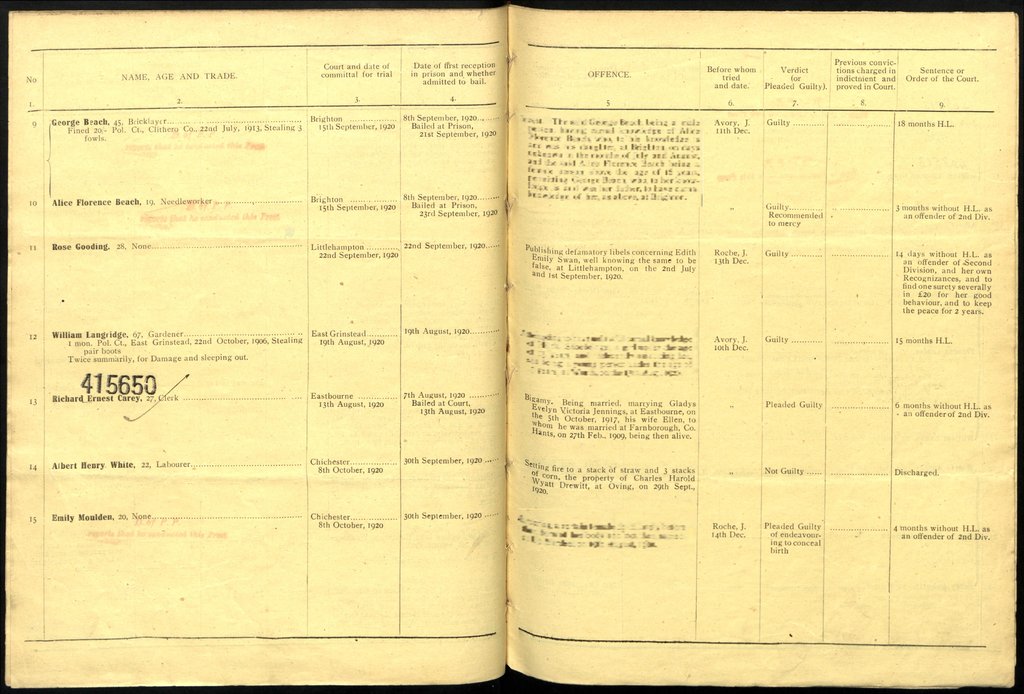

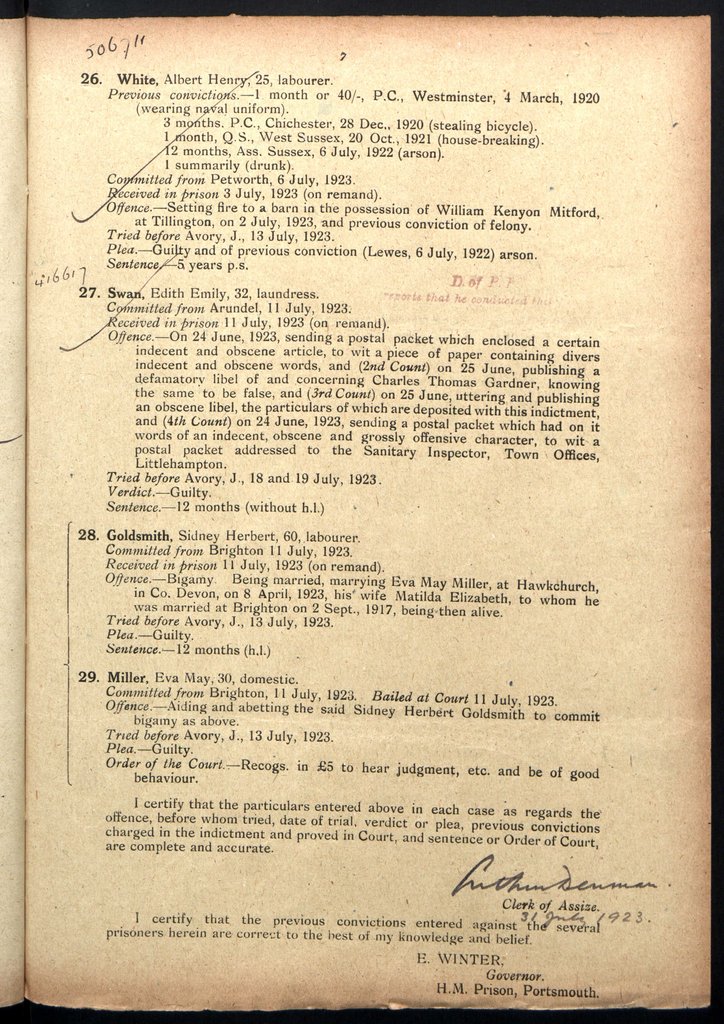

Sussex assizes calendar of prisoners showing an entry for Edith Swan’s second trial

Date: July 1923

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

In June 1923, Edith was caught in a ‘sting’ where invisibly marked postage stamps were sold to her and found used on libellous material sent to the local sanitary inspector, Thomas Gardner. Edith was formally charged and her trial took place on 18 and 19 July at the Sussex assizes.

This Home Office document shows that Edith faced four charges. These included 'publishing a defamatory libel of and concerning Charles Thomas Gardner, knowing the same to be false, and … on 24 June, 1923, sending a postal packet which had on it an indecent, obscene and grossly offensive character, to wit a postal packet addressed to the Sanitary Inspector, Town Offices, Littlehampton.'

This time Edith was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment.

1939 Register entry showing Edith Swan in East Preston Institution, Worthing

Date: 1939

Catalogue reference: View the record N/A in the catalogue

The 1939 register shows Edith in East Preston Institution, Worthing. This was the former workhouse, and Edith is listed as incapacitated. She died twenty years later, still living at the same address, although by then it was a residential home run by West Sussex County Council, known as North View Home.

Many reports at the time of her conviction considered whether Edith was suffering from mental illness as her behaviour was at odds with her respectable and controlled demeanour. At the time the events took place, Edith, born in 1891, was a young woman sharing a small home with her parents and two brothers. As the daughter, she was responsible for the care of the family, and it’s easy to imagine she may have felt trapped and stifled by her situation.