Plague

The second plague pandemic, often known as the Black Death, first came to Britain in 1348 and would have a devastating effect for the next three centuries. Efforts to guard against the spread of the pandemic can be found among the records of our collection, from individuals and the state.

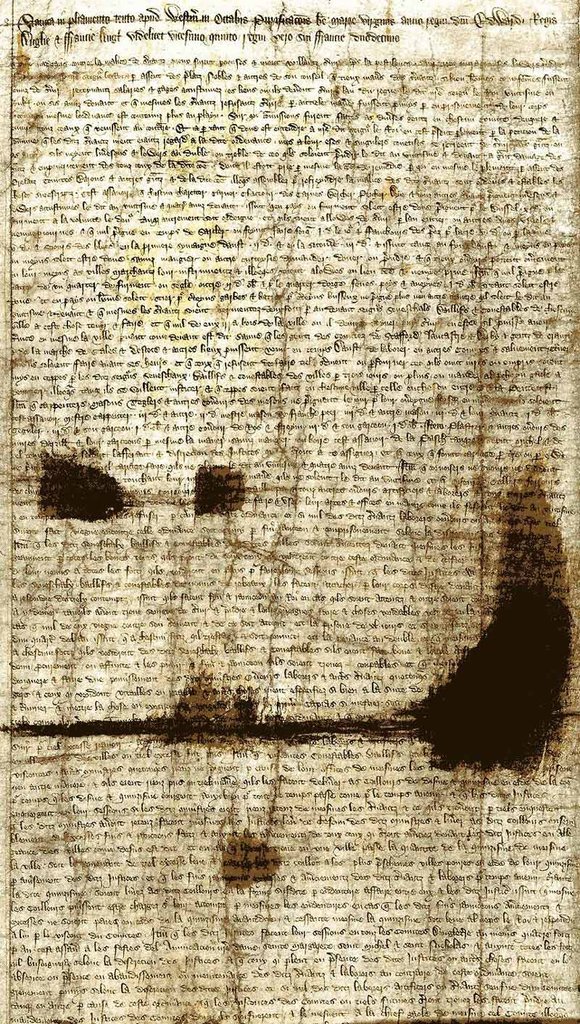

The Statute of Labourers

Date: 1351

Catalogue reference: View the record C 74/1 in the catalogue

The Statute of Labourers was enacted in response to the economic difficulties that emerged after the first outbreaks of the plague in England in 1348. The statute was designed to provide new labour regulations in a restricted labour market. The statute of 1351, supplemented an earlier ordinance of 1349, in which year Parliament had been unable to meet due to the Black Death.

The statute and ordinance were designed to combat rising wages (by regulating the maximum an employer could pay), to control the movement of labourers, to mandate employment for all able-bodied workers, and to prevent the poaching of servants from employment on the promise of more generous terms.

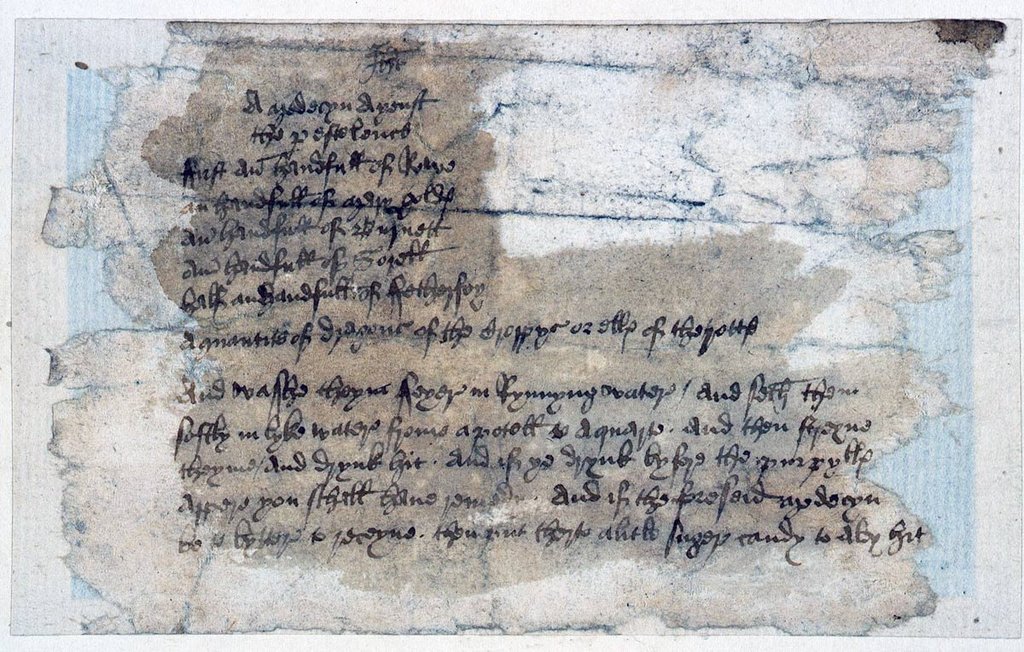

A remedy against the plague

Date: Early 15th century

Catalogue reference: View the record E 163/22/2/60 in the catalogue

This 15th century recipe for a medicine against the outbreaks of the second plague pandemic – 'A medycen ayenst the pestilence' – which had arrived in England in 1348, uses simmered herbs and flowers as the basis for its medicinal properties, including marigolds, sorrel, and burnet.

These and other ingredients were washed in running water and simmered in hot water before straining the mix and drinking it. The recipe states that if taken before ‘the purple [buboes or purple patches on the skin] appear’ then it will give remedy. If it was too bitter to swallow, the recipe recommended adding a small quantity of sugar cane to make it bearable.

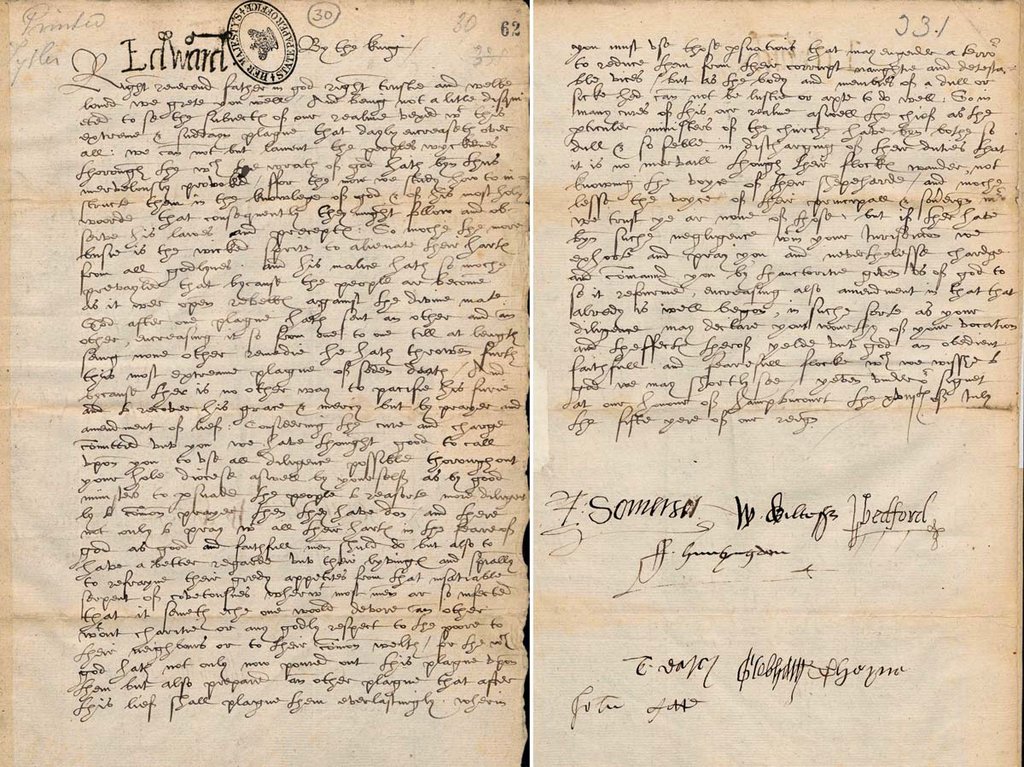

Edward VI's letter to the bishops regarding plague

Date: 1551

Catalogue reference: View the record SP 10/13 in the catalogue

The plague was believed to have been sent by God, and alongside practical ordinances to try and halt the spread of disease the state also encouraged religious measures, particularly after England’s break with the Roman Catholic Church. In this letter, Edward VI writes to his bishops to express his disquiet at seeing his subjects vexed with the plague, because they had been corrupted by the devil to ‘rebel against God’.

Edward ordered the bishops to persuade the people to resort more diligently to prayer, to refrain from greed, and to turn away from their corrupt lives. The king told them to ensure the ministers of the church were not themselves acting in a corrupt manner in discharging their duties.

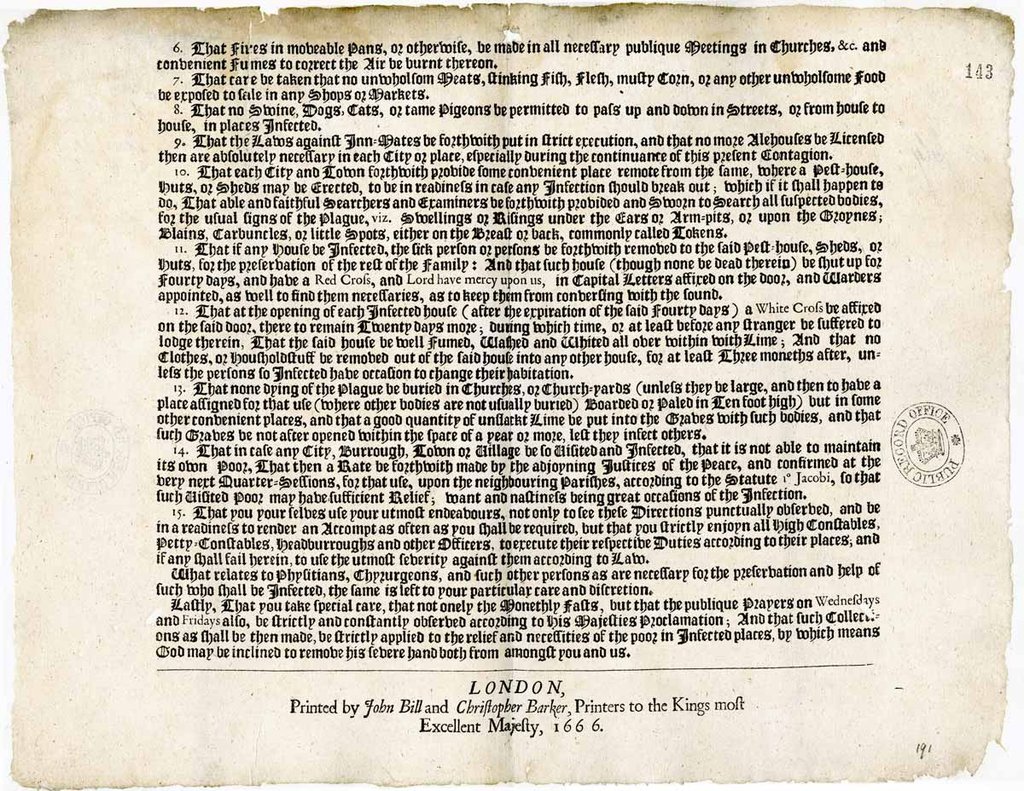

Official orders for the prevention of the Great Plague

Date: 1666

Catalogue reference: View the record SP 29/155 in the catalogue

Over the course of the 16th and into the 17th centuries, regulations against the spread of plague became increasingly stringent, both in London and across the country.

These ordinances from the Great Plague of 1665–1666 included certificates of health – a measure which had been particularly effective in Italy in previous centuries – and restrictive control of individuals and their movements, such as the prohibition of public meetings and gatherings. Dogs, cats, and tame pigeons were not to walk freely in the street. Any houses showing infection were to be quarantined and shut up for 40 days and marked with a red cross and the words ‘Lord have mercy on us’ until any signs of infection had passed.