Record revealed

Sir Henry Cole’s rat

Our collection includes many weird and wonderful records – one of the weirdest is undoubtedly a small box containing the remains of two long-dead rats. But not just an oddity, the story of their 1836 arrival plays a fascinating role in The National Archives’ history.

Image 1 of 2

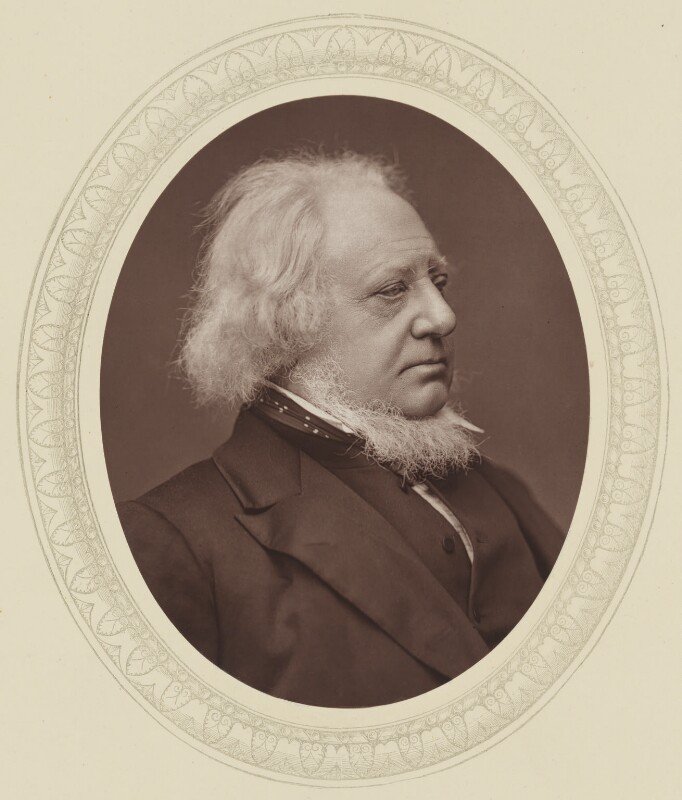

The remains of a rat used by Sir Henry Cole to demonstrate the dire consequences of poor archival practices. It's now in the repositories at The National Archives.

Image 2 of 2

A photograph of Sir Henry Cole by Lock & Whitfield, 1877. Early in his career, Cole was a leading figure in the successful campaign to improve the state and accessibility of the public records. This led to the establishment of the Public Record Office, where for a time he worked as a senior assistant keeper.

NPG Ax17532, © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Why this record matters

Date: 1836

Catalogue reference: E 163/24/31/9

Up until the early part of the 19th century, there was no centralised system for organising and archiving the records of central government or the law courts. Different records were kept in various different store rooms in and around London, often in completely unsuitable conditions, and usually inaccessible to ordinary members of the public.

In 1831, a Record Commission was established, the last in a series of such commissions set up to examine the problem of government recordkeeping and to try and bring some order to the chaos. However, the Commission gained a reputation for inefficiency and lack of progress, and in 1836 a Parliamentary Select Committee was set up to inquire into its work.

One of those called to give evidence to the Committee was a young man called Henry Cole, who had been employed by the Commission as an editor and who had been outspoken in his criticism of its methods. Cole reported to the Committee that in 1833 he had been employed to catalogue the records of the King’s Remembrancer held at the King’s Mews. He recalled that some of them had been in a terrible state, damp and decaying, and that ‘six or seven perfect skeletons of rats were found imbedded’ leading to a dog being employed to hunt out any remaining live rats. The minutes of the Select Committee record that Cole ‘produced and exhibited to the Committee the remains of a cat and some rats’.

Although the minutes do not recall the reaction of the Select Committee to the appearance before them of skeletal vermin, its final report made it clear that much more needed to be done to protect the national records. This led to the Public Records Act of 1838, which in turn led directly to the foundation of the Public Record Office (PRO) and the building of a purpose-built archive on Chancery Lane in London. Cole himself became a senior assistant keeper at the new PRO and had an illustrious and varied career, including being the first director of the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1852. Cole also commissioned the world's first commercial Christmas card. He was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1875.

The records of the King’s Remembrancer were transferred to the new PRO at Chancery Lane, along with the skeletons of the two of the rats found among them. The records have now been transferred to Kew, and the organisation renamed The National Archives. The rats remain in the repositories here, a permanent reminder of the dire consequences of poor archival practices. While one of the skeletons is in rather a poor state, one is still in good condition and is known by staff as ‘Sir Henry Cole’s rat’.

From the shop

-

Henry Cole's rat soft toy – £15.00

Our inquisitive soft toy rat is a much more well behaved and cuddly souvenir to take home.

-

Henry Cole's rat crafting kit – £19.50

Make an archival rat of your very own complete with a monocle and parchment scroll.